Jeremy VerVeer can’t escape his family history. He can’t run. He can’t hide.

Two of his grandparents died of heart attacks in their early 40s and 50s. A 30-year-old uncle died of the same curse. Many other relatives have undergone open heart surgery.

At age 25, VerVeer couldn’t dodge his family footsteps.

The night of Sept. 17, 2005, started like any other for VerVeer, a blues band musician and vocalist in the Grand Rapids, Michigan, area.

His thoughts drifted that night. It had originally been scheduled as his wedding night, but he and Michelle decided to move the marriage date up to June 18 so he could have health insurance sooner.

So instead of standing at the altar and dancing at his wedding reception, he performed on stage.

“I was up in Morley playing at a festival with a blues band I played in,” VerVeer said. “I was singing on stage and started feeling really off. In between songs, I excused myself. I felt like I’ve never felt before.

“It wasn’t painful, not necessarily alarming, but most definitely uncomfortable,” he remembers. “I went for a walk in the woods. About 50 to 60 yards into the woods, I started sweating like I’ve never sweated in my life. I started throwing up.”

He made his way back into the venue.

“By the time I got back to the stage, I took my shirt off and wrung it out,” VerVeer said.

He told his brother, who also played in the band, that he didn’t feel well, that something was really off.

Less than 15 minutes later, VerVeer went to the emergency room at a nearby hospital, feeling lightheaded and outside of himself. He could walk but he felt disoriented, almost like his troubled body was not his own.

Series of attacks

“When I got to the hospital, they said, ‘We have to get you to Grand Rapids (Spectrum Health),’” VerVeer said. “It was a helicopter ride. Luckily we did that because I probably wouldn’t have made it. I had 99 percent closure. I didn’t think I was having a heart attack. It didn’t even cross my mind. I was 25.”

But he was having, and he had, a heart attack. Little did he know, it would be the first of many.

Fortunately, he and his wife, Michelle, had just gotten married. Health insurance kicked in just weeks prior.

Specialists at the Spectrum Health Fred and Lena Meijer Heart Center inserted stents.

“It scared the crap out of me,” he said. “I started going for walks, eating really good. … We pushed ourselves to lead a healthier lifestyle. I went for regular checkups. Everything was fine.”

Until it wasn’t.

Less than two years later, at age 27, as VerVeer played percussion with another band on stage, something felt hauntingly familiar. And it wasn’t the melody line.

“I knew I didn’t feel right,” he said. “I started having familiar feelings.”

His feelings were correct—another heart attack. Again, he landed at the Fred and Lena Meijer Heart Center.

“That was the widow-maker,” VerVeer said of his type of heart attack. “They put a couple more stents in.”

Life rolled along fine for a couple of years.

Then at age 30, during another performance, symptoms struck.

“I was sweaty and not feeling right,” he said. “By this point, I’m pretty familiar with everything. All of my heart attacks were 99 percent closures. The one thing that saved my butt was I had had the heart attack at age 25 and I know what I’m looking for.”

But knowing what you’re looking for in terms of symptoms is completely different than knowing a heart attack could end your life at any moment.

‘I spent so much time worrying’

“It took me a long time to come to terms with the fact my odds are 50-50,” VerVeer said. “I spent so much time worrying.”

The next health hit came not from the heart.

In 2012, at age 32, when he and Michelle were expecting their second child, he saw red in the toilet after urinating.

First thought: bladder infection.

He set up an appointment with a Spectrum Health urologist.

Tests revealed the worst: bladder cancer.

“I didn’t even know what to think,” VerVeer said. “The doctor was talking about taking my bladder out. I went through surgery. I don’t know which I prefer, the heart attack or the bladder cancer.”

After six weeks of chemotherapy, VerVeer zapped the cancer.

“We’re free and clear of that,” he said.

But, wait, there’s more.

This past May, his heart revolted again.

“I was home alone with the kids and just got done mowing the lawn,” he said. “I made myself a bowl of cereal and sat down. All of a sudden, I started sweating really bad. Vivienne, our oldest, saw this happen. I said, ‘Hey, Viv, why don’t you take your sister (Sophia) and go hang out in your room.’ I put the dog away and started packing. I know the drill.”

His heart didn’t have the patience it had in the past.

He had little time to react.

No walk in the woods, no time to plan.

“This time it came real quick,” VerVeer said. “I felt the most uncomfortable I’ve ever felt. I called 911 for an ambulance to the heart center.”

Once there, J. Stewart Collins, MD, a Spectrum Health Medical Group interventional cardiologist, performed a heart catheterization, running a small tube from VerVeer’s wrist up into the heart arteries, where he could take pictures of the arteries using contrast dye and X-ray equipment.

“He had a complete blockage of his right coronary artery,” Dr. Collins said. “We were able to fix the blockage and open the artery using two stents.”

Dr. Collins said having multiple heart attacks at such a young age is very uncommon.

“I’ve only seen a handful of cases in my 15 years of cardiology with a person having multiple heart attacks before age 40,” Dr. Collins said. “He is doing well and fortunately has only had minimal damage to his heart despite four heart attacks. Overall, his heart function has returned to essentially normal. There is a good chance he can do very well long-term with the appropriate medicines and lifestyle changes.”

Dr. Collins said he has encouraged a regular exercise program, participation in a cardiac rehab program and a diet which is primarily plant-based—fresh fruit and vegetables, whole grains, beans and nuts.

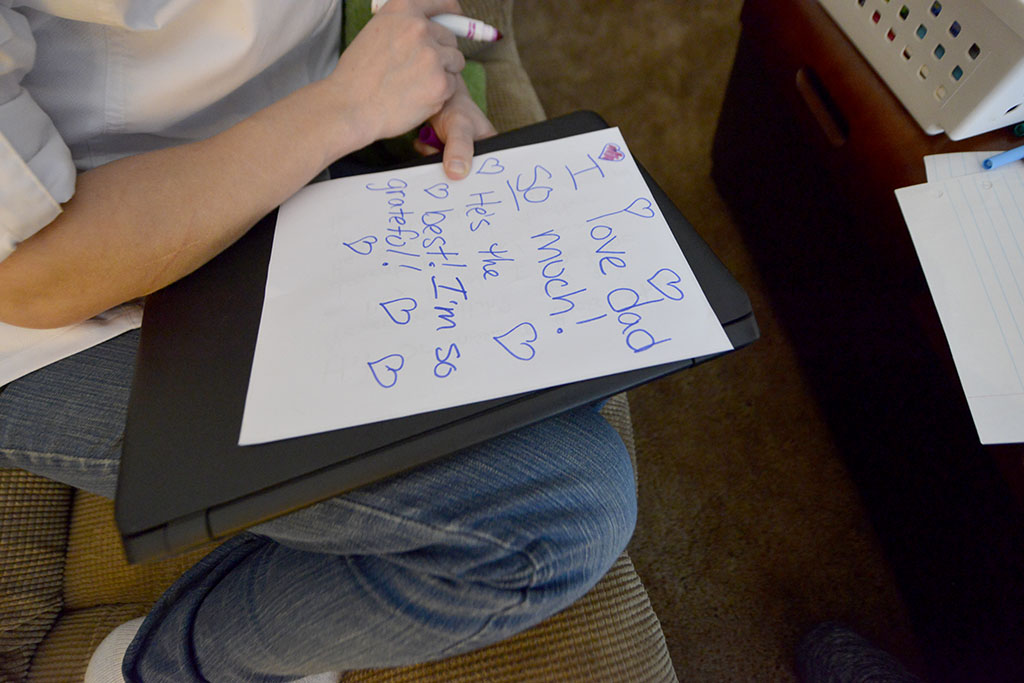

VerVeer said his most recent heart attack got to his head. He constantly worries—not only about himself, but about his oldest daughter, who also has heart issues.

“Vivienne kind of follows in my footsteps,” he said. “She’s 9 and already seeing a cardiologist. Sophia is fine, but Vivienne has my heart issues. She’s going to specialists.”

The heart problems are taking their toll on VerVeer, not only physically but emotionally.

“By the time I was 30, I felt like I was 60,” he said. “I have very little energy.”

There’s also the constant haunting. The nagging. The worry that today could be the day his heart fails again.

‘Definitely in my head’

“Some days I don’t think about it at all,” VerVeer said. “Some days I pay attention to any kind of weird feeling in my body. Some days that voice in the back of your head is just that much louder.

“I have days when I’m just down and out,” he said. “I worry a lot. It took me a long time to even want to leave the house after this last one.”

If he’s playing in a band, or walking by a lake, or camping with his family, the thoughts of his heart are ever-present.

“Those things are most definitely in my head,” VerVeer said. “I could eat as good as I want to eat, I could exercise every day, I could quit doing all kinds of things, but it’s never changed anything. When you’re surrounded by it, it makes it hard.”

Still, he tries to club down the thoughts. He works 60 to 70 hours a week making T-shirts in his basement.

“I make a little extra money in an environment I like,” he said. “I try not to get too stressed out. I try not to worry about it. I try just to wake up happy and go to work.”

Michelle said it hasn’t been easy for her, either.

“When our daughters were babies, I was terrified of him having a heart attack—them being in their crib, defenseless, unable to get help,” she said. “His last heart attack in May, they were 5 and 8. He called me at work and said, ‘You need to come home.’ I just hung up the phone and left. He called me, then called 911 so I would get home to the girls.”

Having experienced the heart attack world for more than a dozen years, the VerVeers said they’ve seen many treatment advancements.

“They went through my wrist last time (with the heart catheter), which was fantastic,” VerVeer said. “The first three times, they had to go through my groin, the femoral artery.

“The first time, I had to lay on my back for 10 hours,” he said. “The second time, they used a star closure, a little device they put on the incision that enabled you to get up within an hour. This last time, they went through my wrist, which was nothing.”

Michelle said the difference in treatment is astounding.

“I thought that was really cool that now they go through the wrist,” she said. “Right after it happened, it was almost like it didn’t happen. He was sitting up and everything. He is going back to his normal life.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

Jeremy is a great guy. I sure hope he’s doing well these days.