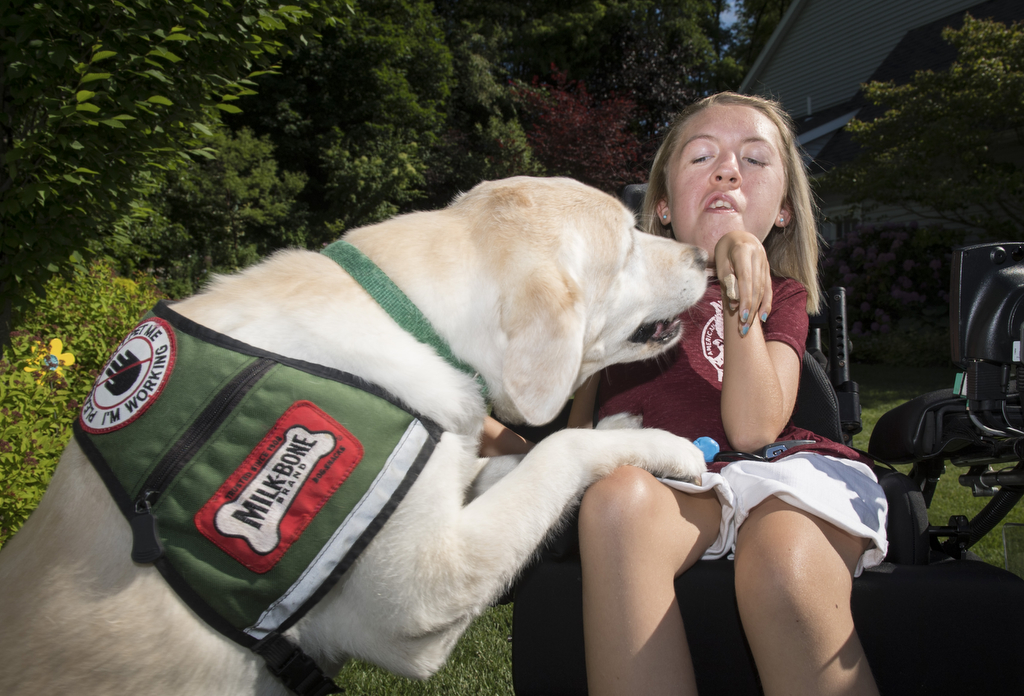

In her 14 years of life, Malorie Fox has never had a medical treatment designed to treat spinal muscular atrophy, the disease that makes her muscles grow weak.

That’s because no such treatment existed―until now.

Malorie, a teenager from Cascade Township, Michigan, recently became one of the first patients in the state to get a new medication that has been hailed as a breakthrough for spinal muscular atrophy.

In December, the Food and Drug Administration approved the drug, Spinraza, a therapy designed to slow the progression of the disease. A clinical trial showed such good results in infants that the study was ended early so the drug could be made widely available.

The day before Malorie received the medication for the first time, she wheeled her motorized chair into an exam room at Spectrum Health Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital, wearing a pink shirt that declared “Being Brave is Beautiful.” Her parents, Michelle and James Fox, and her 4-year-old brother, Jacob, accompanied her.

They met with Jena Krueger, MD, Malorie’s pediatric neurologist, to discuss the treatment. The drug would be delivered through an injection into the spinal fluid.

“I’m nervous and kind of excited,” she said. She explained she worried about whether the spinal injection would hurt, but added, “I’m excited to see what happens.”

Spinal muscular atrophy is a hereditary disease that occurs in 1 in 6,000 to 1 in 10,000 births.

“It causes progressive weakness in the muscles we can control,” Dr. Krueger said. “And right now, we don’t have a cure. We know the natural history of the disease is that once you’re diagnosed with SMA, we see progressive weakness to the point where you may need help breathing or eating or doing things like raising your hands to your face.”

An often fatal disease, spinal muscular atrophy is the leading genetic cause of death from respiratory failure in infants, she said.

The newly approved drug, created by Biogen, works to boost production of a key protein involved in motor development. Patients receive four doses in the first two months. After that, they get a dose every four months.

“Our hope is this drug will prevent (patients) from getting weaker,” Dr. Krueger said.

For Malorie, she said, “My ultimate goal is that she stays steady and keeps the same spirit and spunk.”

Proving them wrong

Malorie was 10 months old when her parents took her to the doctor because she had not met some developmental milestones―such as crawling and sitting up.

A doctor later called Michelle to tell her the diagnosis: Malorie had spinal muscular atrophy.

“We weren’t given much hope,” Michelle said. “They just said she probably wouldn’t live to be 2 years old.”

Malorie is now happy to say “I proved them wrong.” She credits her survival to faith and her parents’ careful care for her.

A freshman at Northpointe Christian High School, she keeps busy with school, family and friends.

“I like to watch TV and hang out with my friends and listen to music,” she said.

Treatments have helped Malorie’s lungs, spine and nutrition. She uses a ventilator when she sleeps, and she receives food through a feeding tube.

But the atrophy of her muscles has progressed.

“She doesn’t have much movement in her hands or arms―or trunk control or head control,” her mom said. “She’s never been able to crawl or stand.”

Over the years, her parents have helped raise funds for research―through golf outings, 5K runs and other events―in hopes of finding a treatment or cure. On Christmas Eve, they heard the news they were waiting for: the approval of the first-ever therapy for spinal muscular atrophy.

Her dad became emotional as he talked about the breakthrough.

“Her whole life has been kind of touch-and-go, so this treatment is going to be a blessing for her and for so many other kids,” James said.

Although the medication aims to slow the progression of the disease, Malorie and her parents hope she will also regain muscle function. They have friends whose abilities improved after starting the medication.

However, her mother said there are many unknowns about the therapy. The clinical trial studied the effect of Spinraza in infants.

“We are not sure what it’s going to do with someone of her age and with the atrophy that has occurred,” Michelle said. “We are just hopeful for anything. Hopefully, it will halt the progression of the spinal muscular atrophy, if nothing else.”

Pediatric neurologists at Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital will closely monitor the patients receiving Spinraza, Dr. Krueger said. The physicians plan to track the drug’s impact on patients and watch for possible side effects.

As research into spinal muscular atrophy continues, Michelle hopes more medical breakthroughs will occur to improve Malorie’s life.

“Now that we have this, I’m even more hopeful that a cure will come,” she said. “I just continue to pray that it will come down the path in her lifetime.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

Praying for her that this treatment will help and give her some improvement.I have been praying for her since I first met her and cared for her. Hugs and love to you Malloy

🙏🙏🙏💕💕💕

Blessings on you dear Mallory. 💜