Like most children on the cusp of 3 years old, Harvey Prins has strong opinions.

He’s partial to the color orange. He loves baths. He’s a fan of Netflix’s “Cocomelon.” He’s especially fond of a rousing version of “Go, Dog, Go!”

What’s unique, however, is the way Harvey tells his parents about all these things that he wants and likes.

Born with cerebral palsy, he can make sounds but he can’t form words yet.

To help him bridge the gap, speech therapists at the Pediatric Neuroscience Center at Spectrum Health Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital have been encouraging him to experiment with a digital device called a Tobii Dynavox.

Harvey communicates by directing his gaze to images that his mom, Kristin, uploaded to the device. With just a glance he can let her know which toy he’d like to play with next.

“Harvey is a vibrant kid and can communicate more than people assume, which is why the speech device is so great for him,” said David Moon, MD, a pediatric neurologist with Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital.

These types of leading-edge speech interventions are among the many advantages of the neuroscience center’s multidisciplinary approach.

Another part of this multidisciplinary approach is Harvey’s care at the Spectrum Health Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital Multidisciplinary Cerebral Palsy Clinic, one of the few comprehensive cerebral palsy clinics in the country.

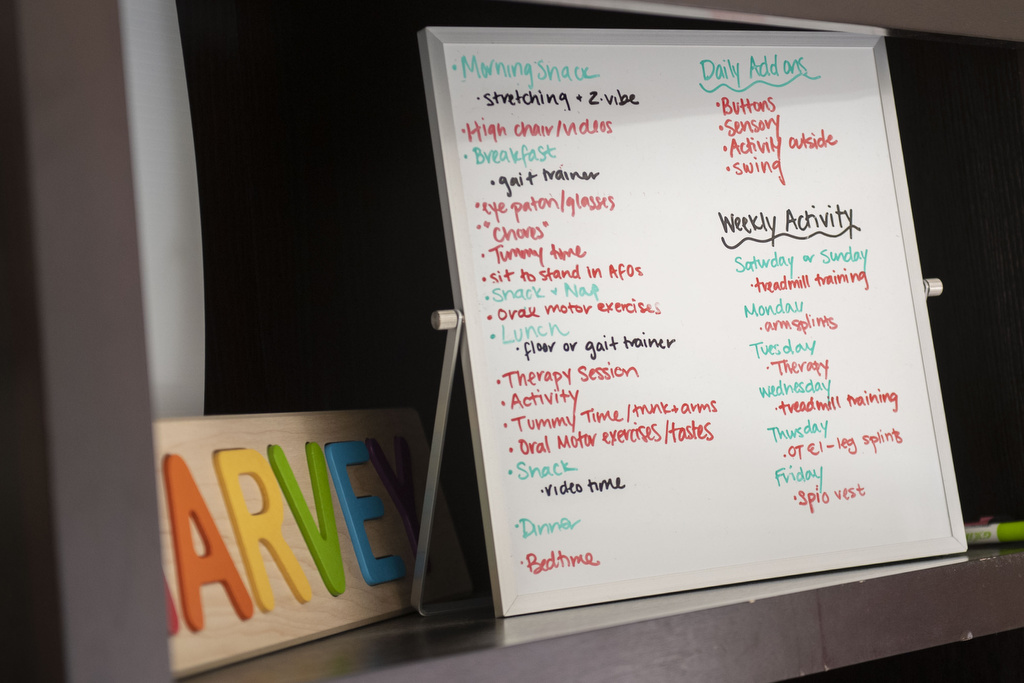

As part of the clinic, in a single day once or twice a year Harvey and his family spend a half-day seeing a pediatric neurologist, a pediatric rehab medicine physician, a neurodevelopmental pediatrician, physical therapist, occupational therapist, speech therapist and orthotist. Social workers and nutritionists are also available.

This special clinic allows a global assessment from multiple lines of specialty at the same time, creating a comprehensive treatment plan, Dr. Moon said.

This kind of holistic treatment helps each specialist see their specific area of focus while also pulling in critical insights from the many other specialties.

“These patients have very complex needs,” Dr. Moon said. “And their care can be quite fractured.”

Coming in once or twice a year for team assessments allows the team to closely track progress, he said.

“We can marshal our resources to make sure the child is getting the best opportunity to grow and develop.”

Growing up

Harvey encountered a complication at birth that caused a lack of oxygen to his brain. This resulted in an injury called hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy—one of the most common causes of cerebral palsy.

At 4 days old, an MRI confirmed the diagnosis. It revealed damage to his brain’s deep structures.

Harvey spent nearly eight weeks in the NICU, plunging first-time parents Kristin and Eric into the intense and bewildering universe of raising a child with special needs.

“It probably took us a year to fully grasp his diagnosis,” Kristin said. “Cerebral palsy can range from mild to severe. And they couldn’t tell us what it would be like for Harvey. So a big part of this journey has been learning to wait and see how he does.”

Harvey’s care, she said, can be incredibly challenging.

“My life is five therapies a week and sometimes the doctor’s appointments seem endless,” she said.

Feeding has been one of the biggest hurdles.

Kristin pumped breast milk for Harvey’s tube feedings for the first 10 months. They then switched to formulas, all while navigating constant spitting up and acid reflux.

“We got a lot of help by working closely with his nutritionists,” she said.

Now 25 pounds, Harvey relies on a tube to help him with meals. He eats six times a day.

Kristin is a stay-at-home mom. Eric, a third-generation dentist in a family practice in Fremont, Michigan, also spends as much time with Harvey as possible, including Wednesdays and weekends.

Early on, she said, they discovered plenty of help on social media. She remains grateful she connected with other parents on Facebook and Instagram.

“It’s been so beneficial for me to talk with other parents who totally understand,” she said.

It also helps that an aunt works in neurodevelopment at Spectrum Health.

“She’s been a tremendous resource for us, too,” Kristin said.

And Harvey gets more active all the time. He walks with the help of a gait trainer, a wheeled device that helps him learn to move his feet.

“It’s still hard for him to sit up without support because his legs are so tight, so he needs support to do that,” Kristin said.

He’s a constant explorer, too. When the situation calls, he’ll simply army crawl to get where he wants to go.

Great expectations

While Harvey’s diagnosis is precise, the scope of his abilities for the future remains less clear.

Time will tell.

“Initially, it’s hard to know exactly which issues a child will face,” Dr. Moon said. “We can’t necessarily know which pathways are injured. And while injured neurons wither away in some parts of the brain, in others, they can heal themselves. Neural pathways can sprout new connections and reroute themselves.”

There is promising research underway into therapies that might encourage that healing, including the use of stem cells.

But those efforts are still in their infancy.

“Currently, the standard of care is early intervention through therapeutic services, as well as targeted medical and surgical interventions as needed,” Dr. Moon said.

This might include treatments like bracing, casting, medications, Botox or phenol injections, intrathecal baclofen pumps, selective dorsal rhizotomy, deep brain stimulation or orthopedic procedures.

Patients can try out new adaptive devices such as the communication tool Harvey has been using.

The goal? Treat the whole child to ensure they function at their highest possible level. To ensure they enjoy the highest quality of life.

But ultimately, even with the best medical care and multiple types of expertise, parents are the experts with their own children, the doctor said.

“We only see them for short periods and get snapshots of who they are,” Dr. Moon said. “But their families live with them 24/7 and have a better sense of what their child can do.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>