As diseases go, there is always an element of thievery at play.

Ashlyn Fite learned this younger than most—at age 18. That’s when asthma first stole her breath.

She quickly came to see how this disease was no garden-variety thief. It was a chronic and consummate plunderer.

Inside of four years, asthma forced her to relinquish hobbies, fitness activities, pets, an apartment and even her favorite haunts.

“It changed my life completely,” said Fite, now 22. “I had to get rid of my two cats, all the candles in my apartment. I had to move to a new place.”

Inadequate treatments

From her late teens up until this past year, the Grandville, Michigan, resident hopped hopelessly from one treatment to the next: Singulair, allergy shots, inhalers, the steroid prednisone, a nebulizer machine to deliver medicine-rich mist directly to her lungs.

While most asthmatics will see substantial improvement with these treatments, people with severe asthma typically find relief to be frustratingly elusive. About 26 million Americans have asthma, and about 5 percent of them battle the severest form of the disease.

It can have a profound impact on patients, said Marc McClelland, MD, a pulmonary and critical care medicine physician at Spectrum Health Medical Group.

“It can control their lives,” he said. “It can make it so they have great difficulty in exercising, or doing any physical activity. Often they gain weight. Often they need to take prednisone, which can have a lot of serious side effects.

“Severe asthma can have a big impact on quality of life,” he added.

Predictably, the standard medications did little to reduce the frequency or intensity of Fite’s attacks.

She was hospitalized six times for severe episodes, most involving a one-two punch of asthma and pneumonia.

“In those three and a half years, it seemed like we tried almost every inhaler and prescription medicine that can be tried for asthma,” Fite said. “Sometimes when it’s really bad, I can’t even talk as much. A lot of times I have a cough, headaches—excruciating headaches if my oxygen is low, and I definitely get tired. It’s exhausting.”

Just a decade ago, this former competitive dancer would have been limited to the available treatments, unremarkable as they may be.

But in 2010, medical industry colossus Boston Scientific rolled out a new option: Bronchial thermoplasty, a first-of-its-kind procedure strictly for severe asthma patients.

Fite learned of the procedure last year.

“It changed my life,” she said.

Limited audience

Bronchial thermoplasty is designed for severe asthma sufferers—a relatively small segment of asthmatics, but a group nevertheless in dire need.

Spectrum Health tried the procedure four years ago as part of a clinical trial. The impressive results led the hospital system to add it for good, Dr. McClelland said.

Apart from a cluster of facilities in Detroit, there are just four locations offering bronchial thermoplasty in Michigan. Spectrum Health is the only location in the western part of the state.

Dr. McClelland is emphatic on a critical point: The treatment is not for everyone.

Persistence pays

Bronchial thermoplasty is an exciting new treatment for severe asthma sufferers, but be warned: It’s pricey.

A catheter for just one session is $2,500, and the full scope of treatment entails three separate sessions.

Insurers have been reluctant to give their blessing.

“The insurance coverage for it is very spotty,” said Dr. Marc McClelland. “For whatever reason, it’s been slow to receive approval. Some policies pay for it—Medicare and Medicaid pay for it.”

Ashlyn Fite, who underwent the procedure in the fall, said she got her insurance company’s approval on the third try.

“It’s only for patients with severe asthma who can’t control it through any other means,” he said. “The vast majority of asthmatics do not need bronchial thermoplasty. Most people with run-of-the-mill asthma can control it with inhalers and medication and lifestyle modifications.”

The procedure is not a cure-all, either, “and it doesn’t eliminate the need for medications altogether,” Dr. McClelland said.

Yet it certainly comes close.

‘On top of the world’

A full course of bronchial thermoplasty involves three sessions, each about three weeks apart: the bottom half of one lung treated in the first session; the bottom half of the other lung in the second; the top half of both lungs last.

Each session is about an hour, followed by a few hours of observation. It’s a minimally invasive outpatient procedure.

The bulk of patients who undergo the treatment will immediately see a drop in the frequency and severity of their asthma attacks, which means fewer trips to the emergency room and fewer doses of medication, Dr. McClelland said.

Boston Scientific says patients can see the number of severe asthma attacks cut by a third and the number of emergency room visits cut by more than 80 percent.

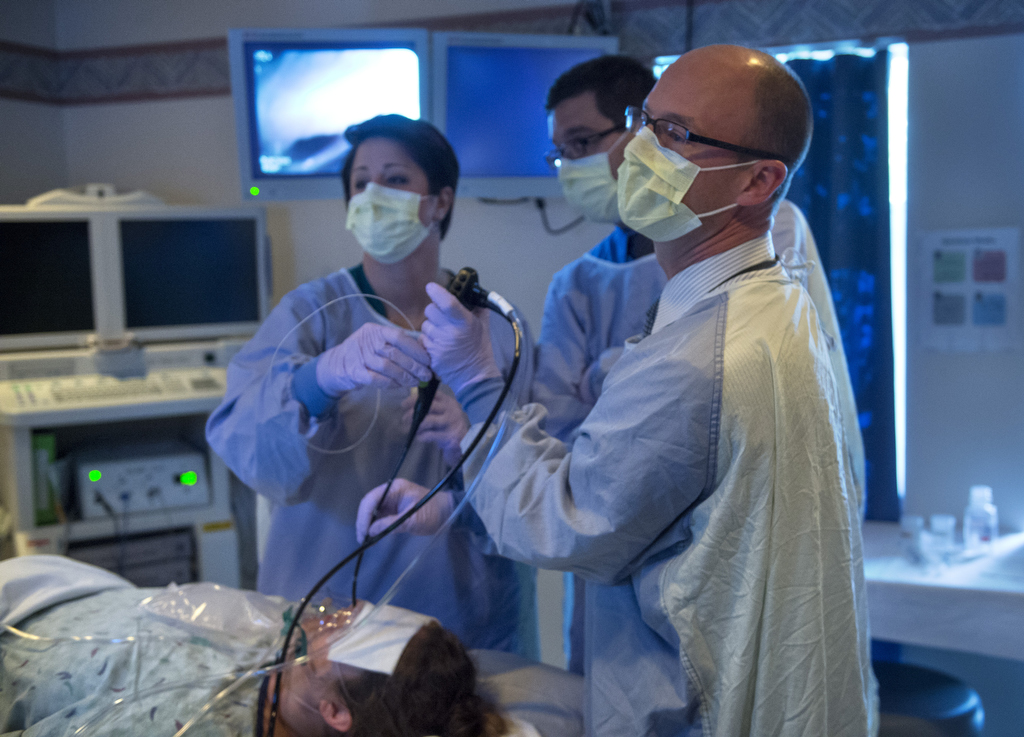

The procedure: After the patient is sedated, the doctor inserts a bronchoscope into her mouth or nose, wending the device into the airway. A catheter then extrudes from the tip of the device.

“Once it’s in the right spot, I open it up and the wires of the catheter apply a type of energy to the airway wall,” Dr. McClelland said.

This heats the smooth muscle in a controlled fashion.

“Over time, that makes the smooth muscle less reactive—so it’s less likely to constrict or narrow the airways,” he said. “This basically reduces the symptoms of asthma.”

Fite’s first round was in September.

“I woke up 45 minutes later feeling drowsy,” she said. “Four hours afterward, I was sent home.”

She went back to work the next day, feeling, as she recalls, “kind of crummy.”

“A little short of breath, a little chest tightness,” she said.

But then something happened.

“After about three to five days, I’m feeling like I’m on top of the world and I could run a marathon,” she said.

The reclamation

It was the same story after the second session and an even better story after the final session.

“I have been feeling great,” Fite said in November, shortly after the final visit. “I have been back in the gym for about two weeks on a regular basis, and feeling better than ever.”

Instead of using her emergency inhaler up to 35 times a week, she now uses it four times a week, although she still has a maintenance inhaler.

As the procedure is relatively new, its effectiveness beyond five years is unknown. It could last longer, but only time will tell.

“Nobody knows if it needs repeated or if it would be indefinite,” Dr. McClelland said. “That’s to be determined.”

For her part, the aptly surnamed Fite is finally able to battle back. With help from modern medicine, she is reclaiming much of what asthma stole.

“I was always really excited to hopefully have results,” she said.

One of her favorite pre-asthma haunts was US 131 Motorsports Park in Martin, Michigan, where her boyfriend and friends drag race. She had to steer clear of the raceway when she developed asthma because the pollutants harmed her lungs.

Post-thermoplasty? “I hope I can go a lot more this year,” she said.

She’s not stopping there.

“I actually signed up to do a half-marathon in April,” she said.

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

Hope many children can benefit from this new procedure. Nothing worse than seeing someone trying to take a breath. Thanks to Ashlyn willing to share her procedure experience and the staff forgiving her that ease of getting that deep breath.