Imagine feeling like you can’t go out anywhere, unless it’s a place where a bathroom is nearby.

Then imagine being too embarrassed to talk about this medical problem with anyone—even your own doctor.

Millions of people with fecal incontinence know exactly how this feels.

But Heather Slay, MD, a colorectal surgeon with Spectrum Health Medical Group, urges patients to seek help, because there are plenty of treatment options available.

Some are simple, some are surgical.

“It can be very embarrassing, but I encourage patients to talk with their doctors about it so they can learn about the treatment options,” Dr. Slay said. “Patients often tell me, ‘I won’t leave the house,’ or ‘I will only leave when I know there are bathrooms close.’ It really affects their lifestyle.”

She also wants them to know they’re not alone. While the incidence is hard to pin down—patients are often reluctant to report—fecal incontinence affects anywhere from 2 to 18 percent of the population.

It’s more common in women and it affects patients of all ages, Dr. Slay said.

Causes

Fecal incontinence is the inability to control bowel movements, although it varies from occasional leakage to complete loss of bowel control.

Childbirth is a leading cause, according to Dr. Slay, particularly in cases of prolonged delivery, episiotomy and forceps use.

“Often what we see is that women may not have problems for 30 to 40 years after delivery,” Dr. Slay said. “Then, when they are 60 or 70, they develop problems.”

Another major cause is diarrhea, as solid stool is easier to hold in the rectum than liquid, or soft, mushy stool.

“The rectum is right above the anal sphincter, so you can imagine that with liquid stool, the rectum doesn’t get a chance to play its role,” she said.

Constipation, the opposite problem, can also cause fecal incontinence. If someone doesn’t have a bowel movement for an extended time, it can cause hard, dry stool to develop and build up in the rectum. Liquid stool can then actually pass around it, or overflow, and leak out, Dr. Slay explained.

Treatments

The simplest treatments start with medication and diet changes to create a well-formed stool. Dr. Slay might recommend Imodium to slow down the colon, or she may also recommend a fiber supplement.

“Fiber is certainly good for colon health in general, and in creating a regular, consistent bowel movement,” she said. She typically recommends a powder fiber substance twice a day, although she said it can take trial and error to find the right amount for each patient.

“I am always amazed at how much fiber and Imodium can help,” she said.

The trick, for people who have tried fiber supplementation without results, is long-term consistency and compliance. It also helps to keep a bowel diary.

Other treatment options include physical therapy or biofeedback treatment with someone specializing in pelvic floor rehabilitation.

Biofeedback is a tool therapists use in retraining relevant muscles to connect with the brain.

In the past, further treatment would often entail surgery called sphincteroplasty, which repairs a damaged or weakened anal sphincter.

While Dr. Slay has used this procedure, she and other doctors grew frustrated that many patients would find themselves right back where they started just five to 10 years after sphincteroplasty.

And while some patients still require this procedure—young patients with an obvious injury or sphincter defect, for instance—it has largely been replaced by a newer and less invasive treatment called sacral nerve stimulation.

Sacral nerve stimulation

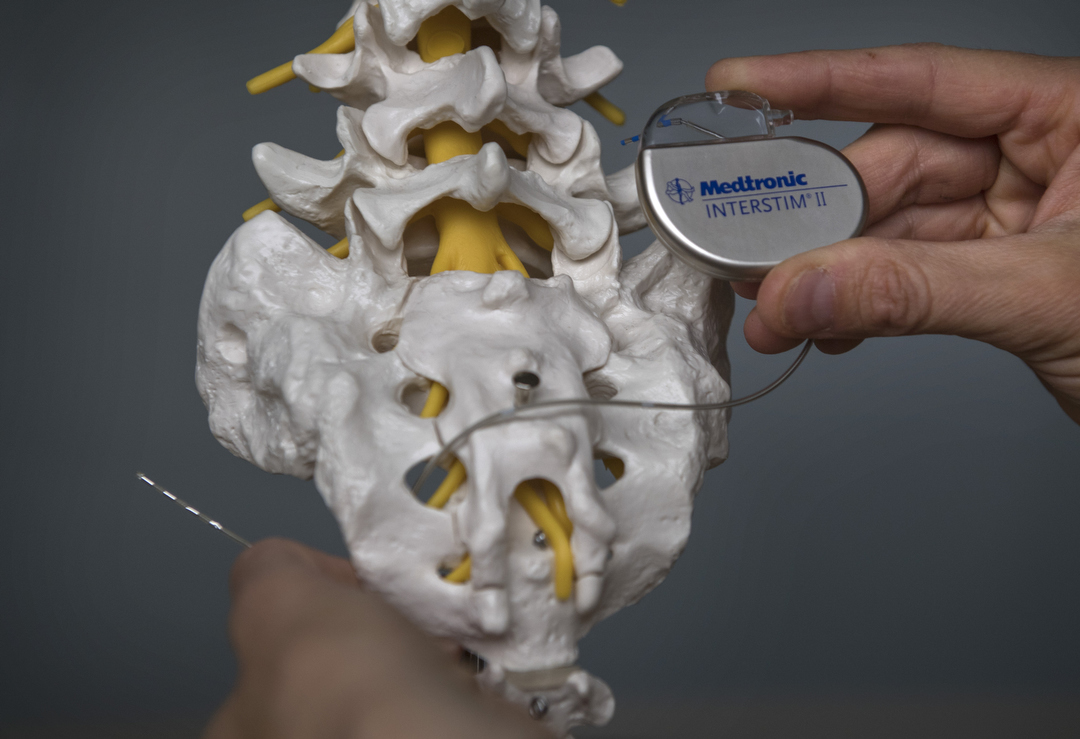

Dr. Slay describes sacral nerve stimulation as something like a “pacemaker for the pelvic floor.”

Doctors don’t know exactly why it works, but they do know it provides a low level of stimulation to strengthen the muscles and nerves of the pelvic floor and bowel.

Patients start with a trial stage in which the device is implanted under the skin in the upper buttock for two weeks, during which time doctors monitor the patient’s response.

“What we are looking for is greater than 50 percent improvement,” Dr. Slay said.

If it works, patients are eligible for surgery to implant the device permanently.

“The success rate (of sacral nerve stimulation) is very good—close to 90 percent,” Dr. Slay said. “These patients have seen greater than 50 percent improvement, which may not be perfect, but it makes a big difference in lifestyle.”

Patients who have tried conservative treatment, and are still having at least two incidents of fecal incontinence per week, are candidates for sacral nerve stimulation, Dr. Slay said.

Patients who require MRIs cannot undergo the procedure, since you cannot have an MRI with an implanted device. Also, difficulties resulting from aging or lack of mental awareness may preclude certain patients from handling the device.

The success stories from sacral nerve stimulation are encouraging.

Dr. Slay recalled an elementary school teacher whose condition often forced her to leave the classroom. Post-treatment, the teacher has seen 100 percent improvement.

“Now she doesn’t have to worry about it,” Dr. Slay said. “She can teach and be there for her students.”

Another patient, she said, lost 60 pounds after the procedure.

“She can get out now and exercise and do the things she wanted to do,” Dr. Slay said. “Before, she stayed at home and didn’t leave.”

Dr. Slay urges patients in similar situations to visit their primary care physician or come directly to her office.

“They should see whoever they are comfortable talking to first,” she said. “We are happy to see them.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>