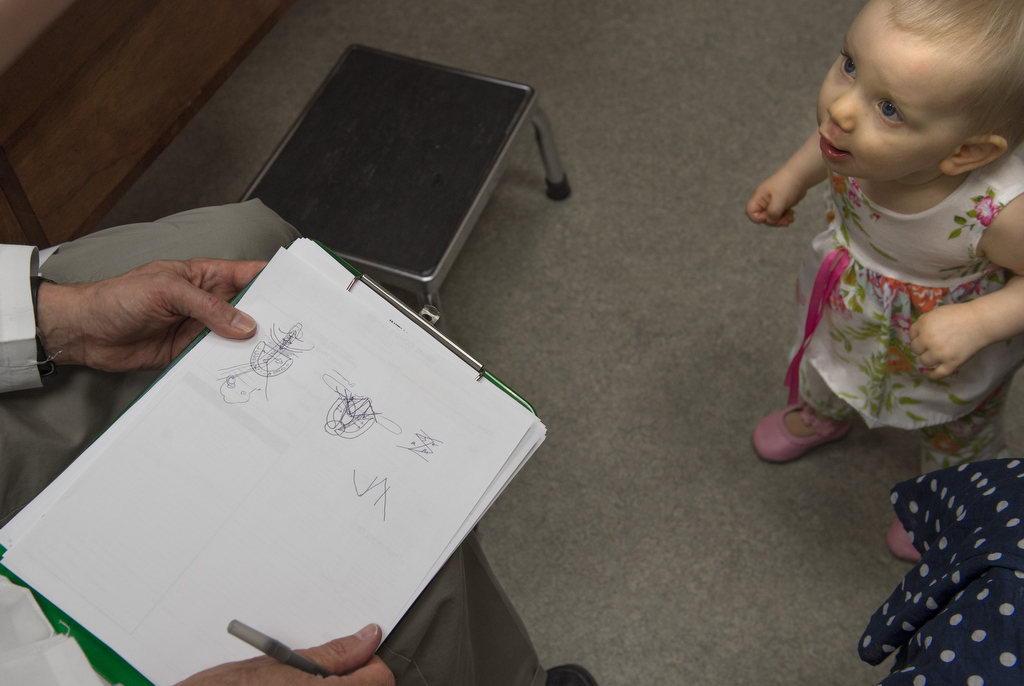

Vivienne VanSickle toddled to her grandmother after a recent surgical follow-up appointment, uttering a phrase perceived as “Nana” in a 15-month-old voice.

She grasped grandmother Lynn’s hand, flashing a broad smile.

A week prior, Vivienne’s mouth wasn’t quite as eager to grin—she had just undergone surgery for cleft palate. And talking isn’t a given. Cleft palate and lip can affect the ability to speak.

But with surgical techniques developed and practiced by Robert Mann, MD, Spectrum Health Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital oral cleft program director, patients like Vivienne have a 95 percent chance of developing normal speech.

“We would anticipate in a few months her speech will start to develop in a normal fashion,” said Dr. Mann, who in 1985 developed a technique to customize the palate surgery for each child’s anatomy. The procedure is called the “Buccal Flap” approach and adds cheek tissue to the palate where tissue is missing because of the birth defect.

“She should really be in great shape,” Dr. Mann said. “The way we do surgery here has an extra high incidence of normal speech. Her prognosis is excellent.”

Vivienne’s mom, Amy, said only a week out, her daughter was “back to her normal self.”

That “normal self” pulled a tiny Tupperware container from her grandmother’s purse and shook it with delight.

As Mom talked about the recent surgery, Vivienne lost her balance and her little bottom plunked to the floor.

Mom and Grandma smiled at the antics of the girl who has traveled so far.

‘It was certainly unexpected’

Amy and her husband, Jeff, an Army officer, were stationed in France last year, where Jeff worked at the American Embassy in Paris.

While there, a four-month ultrasound showed abnormalities.

Cleft lip and palate are birth defects that occur early in pregnancy. As the baby’s face forms, body tissue and cells from each side of the head grow toward the center of the face, where they typically join together.

Cleft palates and lips never join, causing openings or gaps in the lip and roof of the mouth.

According to the Worldwide Health Organization, 1 in every 500 babies in the world is born with cleft lip and/or palate.

Like in Viv’s case, in 80 percent of clefts, there is no immediate family history. The cause of cleft issues is still not known.

“It was certainly unexpected when we found out with the ultrasound, but we just know that God is the one that has knit her together and made her,” Amy said. “We just trust in the one who has made her and what he has planned for her.”

Amy said she has friends who have children with cleft palate, and she did lots of research when she learned of her daughter’s condition.

Last summer, the family flew 14 hours back from France so Dr. Mann could surgically repair Vivienne’s lip.

Surgical innovation and success

Dr. Mann said the “Buccal Flap” approach has stood the test of time, yielding excellent speech and allowing for better facial development with fewer dental distortions.

The addition of tissue to the defect using the cheek buccal tissue is the key to a successful repair, according to Dr. Mann, and allows for good results whether the clefts are narrow or very wide.

“Most places just bring the tissue together that’s available in the cleft,” Dr. Mann said. “They have a single pattern they use for all clefts. That works well, only if the pattern fits the anatomy. We customize our patterns to each child’s unique anatomy.”

A one-size-fits-all approach may lead to more orthodontic issues, speech problems and facial growth can be affected.

“We actually add tissue (from the cheeks) to make up the deficit so growth can be normalized,” Dr. Mann said. “It’s proved to be very effective and now places around the country and world are interested in the results we have achieved here.”

Most people have several folds of cheek tissue to spare.

“You know sometimes how you bite your cheek when you’re eating? That’s the area where the buccal flap is taken from,” Dr. Mann said.

He said he was glad to see a family in the Armed Services come home to have cleft lip and palate surgery done in the United States and wishes more service personnel would do the same.

He expects Viv’s next surgery—to fill the gap in her gums with bone—won’t happen until she is 9 years old.

‘She’s just blossomed’

Given the distance they have to travel, that’s great news for the VanSickles.

“Hopefully she will be surgery-free for a lot of years,” Amy said.

As Amy spoke, Vivienne played with the sole of her mom’s shoe, then toddled over to play horsey, horsey with her grandma.

“Since surgery she’s just blossomed,” Lynn said.

Jeff was in town for the surgery, but has since flown back to Macedonia, a 28-hour trip.

“We’ve observed she’s happy and just full of life, which is what her name means in French,” Jeff said.

Amy said that’s always been their prayer for little Viv. And that her mouth, no matter how malformed, would always be filled with laughter.

“In the scheme of things, cleft lip and palate is pretty minor,” Amy said. “But it’s still an adjustment. She’ll have ongoing needs. We’ll see how her speech progresses, and later with dental and orthodontics. You see pictures and think it’s one surgery and done. But it’s ongoing care, ongoing assessment, really for the rest of her life.”

Vivvy could need surgery into her teens, according to Amy.

But she believes her daughter has the mental makeup to accept this journey with grace.

“She’s a sweet little thing,” Amy said. “But we’ve seen some feistiness, which will probably benefit her in the end.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

3 cheers and a smile for modern medicine and Dr. Mann!

Wonderful article.

My unborn baby girl will be born with a cleft lip and palette