The bull charged out of the gate, bucking and kicking, with Nathan Davis on its back, one hand clinging to the rope.

He lasted a couple of seconds. And then suddenly, he flew through the air and crash-landed in the dirt of the rodeo arena.

Down came the bull’s rear hooves. Boom. Right in Nate’s belly.

The ride was over.

But the race to save Nate’s life had just begun. And it would prove to be nearly as fast-paced and harrowing as a rodeo ride.

All of the care and all of our resources mattered. If one of those things wasn’t there, he wouldn’t be with us.

The stomp on Nate’s midsection didn’t break the skin, but it nearly severed his liver. His survival required a rapid-fire series of events, coordinated by a team of experts―emergency medical responders, surgeons and a Spectrum Health Aero Med emergency flight team.

Plus 150 units of blood.

And prayers. So many prayers.

“Nathan was truly one of those blessings where God said, ‘I’m going to align all this and help you through this,’” said Meghan Wright, CFRN, EMT-P, an Aero Med flight nurse. “Every second mattered. Every person’s hands that touched him mattered. All of the care and all of our resources mattered.

“If one of those things wasn’t there, he wouldn’t be with us.”

A crazy adrenaline rush

Nate sat recently at the kitchen table in his farmhouse north of Clare, Michigan, a spot surrounded by green fields, woods, a budding crop of hops and a branch of the Tobacco River.

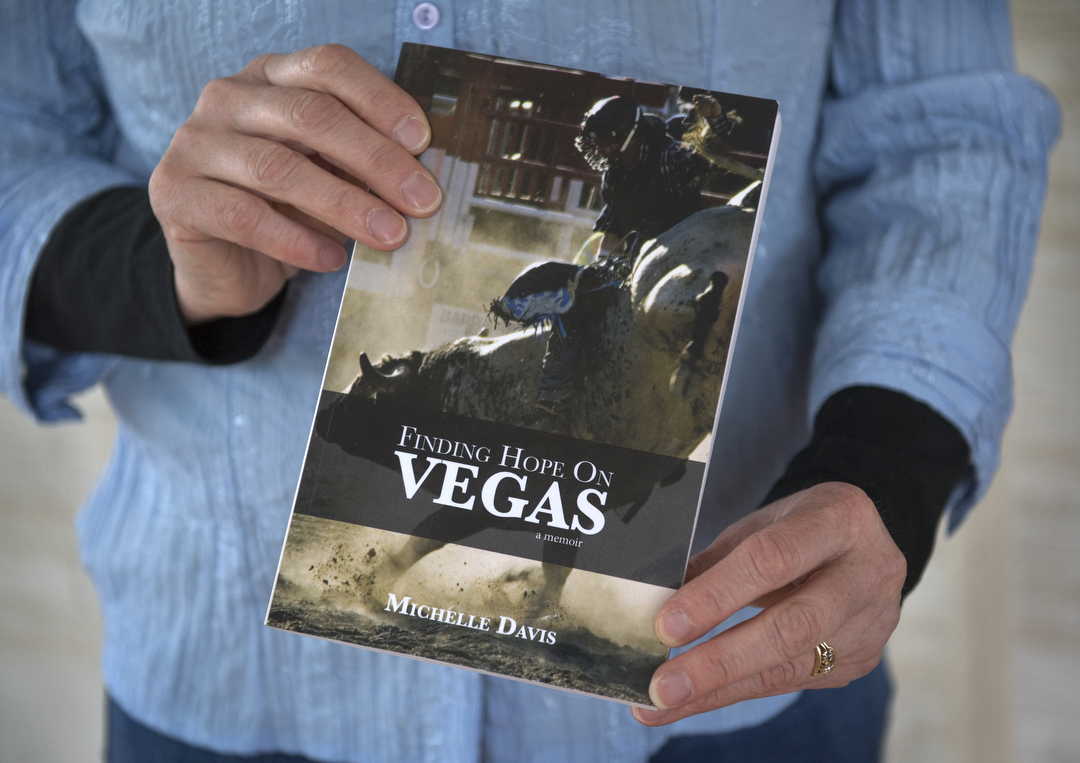

Beside him, his mother, Michelle Davis, held the book she has just published about his experience, “Finding Hope on Vegas.”

She filled in the gaps as Nate told his story. There’s a good two weeks he can’t recall.

I remember making a couple of jumps with (the bull), and then I was looking up at the sky. I was just thinking the wind got knocked out of me.

Nate, now 20, grew up in a family of five children on his parents’ hobby farm. He raised cattle, hunted and fished, and worked on neighbors’ dairy farms. Tall, lean and athletic, he liked sports—he played football and soccer as a kid.

Bull riding seemed like a natural fit. When his friends started to compete, he jumped in, too. And loved the thrill of it.

“Riding bulls is a huge challenge. Huge,” he said. “The adrenaline rush is just crazy. It was like through-the-roof crazy.”

The goal for a bull rider is to stay on the bull for 8 seconds, hanging on with one hand. The intense, chaotic ride seems to last half of forever. Nate managed to reach 8 seconds a couple of times before being tossed off by the bull, but never in competition.

“They say it takes 100 rides to even remember what you’re doing,” he said.

Nate had been riding bulls for a year―about 20 times in all―when he began his last ride on Aug. 9, 2014, at the rodeo at the Gratiot County Fair in Alma, in central Michigan. About 7 p.m., he climbed on a bull named Vegas. He heard his name called and the gate opened. The rest zipped by in a blur.

“I remember making a couple of jumps with him, and then I was looking up at the sky,” he said.

He can’t tell you how it felt when the hooves of a 1,500-pound bull pinned him to the ground. He doesn’t remember that part.

“I was just thinking the wind got knocked out of me,” he said. “I could barely breathe.”

Bullfighters helped him stand and walk from the arena. When he saw his worried mother’s face, he grabbed her hand. “I’m fine, I’m fine,” he remembers telling her.

But by the time Nate reached the ambulance and stretcher, his vision went dark. He thought he had gone blind.

Too sick to transfer

The ambulance rushed Nate to Mid-Michigan Medical Center-Gratiot. It was around that same time that an Aero Med flight helicopter lifted off, headed to help another patient.

While they were in mid-air, the dispatcher canceled the call. Pilot Paul Reges turned the helicopter around. That’s when the call about Nate came―the crew learned a patient had been taken to the hospital in Alma after being injured by a bull.

The timing―with the helicopter already airborne and the other call canceled―shaved precious minutes off the response time for Nate, said Harry Pindell, CFRN, EMT-P, one of the two flight nurses in the helicopter.

The Aero Med crew arrived at the Alma hospital at 8:15 p.m.

The nurses and the hospital’s staff agreed that Nate, bleeding profusely internally, was too fragile to transport. The surgeon, Jeffrey Bonacci, MD, performed a damage-control laparotomy―opening up the abdomen to pack it with sponges to slow the bleeding.

Then the nurses transferred him to the Aero Med stretcher.

“We had to transfer him to all our monitoring devices, our ventilator,” Pindell said. “All of his drips had to be moved over.”

Nate continued to receive blood transfusions, pressed in at a rapid rate, to try to compensate for the steady loss of blood from the torn liver.

As the nurses wheeled him down the hall, Nate’s parents and brothers got a brief moment to say goodbye.

“Hang in there, Nate,” Michelle told him. “I’ll see you in Grand Rapids. Do you hear me Nate? Just hang on until we get there.”

“Stay strong, Nate,” his father had said.

It was a fairly miraculous recovery. The fact that he was 17 years old was a big factor. I’m sure prayer had a big part to do with it, too.

Nate’s mother had wrapped a religious medal on a chain around Nate’s foot after his injury. The medal contained a religious relic. The nurses tried to give it back to her, but Michelle pressed it on them. “We will lose it,” Wright told her.

“I don’t care,” Michelle said. “It has to go with him.”

She gave Nate a kiss and then broke into sobs as the nurses loaded the stretcher on to the helicopter. She kept up a nonstop recitation of the rosary, as her heart spoke directly to God.

“He’s a good kid,” she told him. “I know he’s yours, but I’m not ready for him to go.”

Michelle and Tim watched and prayed as the helicopter rose and disappeared into the dark sky, with only a flashing light to mark its location. And then they drove to Grand Rapids.

In the helicopter, the nurses continued to aggressively infuse blood. They worked to keep Nate’s blood pressure up while keeping him sedated and breathing well through the ventilator.

“You don’t even know you’re flying at 2,500 feet at 160 miles an hour, you’re so in tune with what’s happening with the patient,” Pindell said.

The drive from Alma to Grand Rapids takes about an hour and 20 minutes. The Aero Med helicopter arrived at the helipad on the roof of Spectrum Health Butterworth Hospital in about 30 minutes.

The nurses brought Nate to the emergency department. Five minutes later they wheeled him into the operating room, where pediatric and adult trauma surgeons began to work on him.

‘On death’s door’

“There was a crushing injury. It tore a section of the right lobe of the liver,” said Carlos Rodriguez, MD, one of Nate’s surgeons and the medical director of Spectrum Health surgical services. “The liver is highly vascularized, so it bled a lot.”

Nate faced three “enemies,” Dr. Rodriguez said. He could develop hypothermia, his blood could lose the ability to clot, and his body could release acidic compounds that damage tissue and organs.

“All lead to death,” he said.

The trauma team used a “massive transfusion protocol” to pump blood, plasma and platelets into Nate, as the surgeons worked to control the bleeding.

They turned to an interventional radiologist for help. Working through a catheter threaded through an artery, he placed tiny coils in the still-bleeding blood vessels in the liver to block the flow of blood.

With the coils and the packing, the blood loss slowed enough for Nate to stabilize.

For the next 12 hours, he lay “on death’s door but not actively dying,” Dr. Rodriguez said.

The next day, Nate hit another crisis. He developed abdominal compartment syndrome, a condition in which a build-up of pressure reduces blood flow to the organs. Jennifer Fromm, MD, a surgical resident, performed an emergency procedure at his bedside to relieve the pressure.

Then, in the operating room, surgeons removed the damaged part of the liver.

“It was touch and go,” Michelle said.

Nate remained in the Butterworth Hospital intensive care unit―on a ventilator, on dialysis and on medication to keep his blood pressure up. He underwent a few more procedures over the following two weeks, but his condition steadily improved. After two weeks, he transferred to a room at Spectrum Health Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital.

He gradually became aware of his surroundings. Michelle rejoiced when she noticed his eyes blink one day.

“Blink if you can hear us,” she had said to him.

Nate blinked again. He remembers that simple action―and that it took tremendous effort.

“It was a fairly miraculous recovery,” Dr. Rodriguez said. “The fact that he was 17 years old was a big factor. Teenagers and people in their 20s are very resilient. They are able to survive tremendous things.

“I’m sure prayer had a big part to do with it, too.”

For Nate, the overnight change in his strength was hard to comprehend.

“I went from being an active 17-year-old to somebody who can’t get out of bed without help,” he said.

His legs sustained nerve damage and he underwent physical therapy to regain the ability to lift his feet and walk.

Today, he has come back almost 100 percent.

“I don’t think there’s anything I can’t do,” he said. “I can’t run great. I’m still working on it. But I’m close―a lot closer than I thought I would be.”

It took a big team to bring him to that point, said James DeCou, MD, the trauma program director at Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital. A point of pride, he noted: Dr. Bonacci, the surgeon who saved Nate’s life in Alma, trained in Spectrum Health’s residency program.

“He knew exactly what to do and where to send him and how to get him here,” Dr. DeCou said. “It makes us feel good just to know he did such an amazing job on his end at this small hospital.”

At Spectrum Health, Nate benefited from the combined expertise of pediatric specialists and the resources of Butterworth Hospital’s level 1 trauma center.

“He had incredibly severe injuries. It’s amazing he is walking and talking,” Dr. DeCou said. “So many services and people helped with this boy, one way or another. It all came together to save his life.”

An Aero Med reunion

More than a year after the injury, Nate came to Spectrum Health for his last follow-up appointment. He and his mother stopped by the Aero Med office to say thank you to the nurses and pilot who kept him alive en route to the hospital.

“It was a great reunion,” Michelle said. “There were hugs and a few tears. I just felt so much gratitude toward them. I wanted to personally thank them myself.”

Just the sight of Nate looking strong and healthy lifted the crew’s spirits.

“It seems Nate’s story was nothing short of a miracle,” Pindell said. “He was so sick, his chance for survival was slim. To see him come back from that just shows that all the things that happened that day worked well for him.”

Faith and family

At home, Nate held out the religious medal his mother sent with him on the Aero Med helicopter three years ago. Like Nate, it survived the chaos of the night. Now, he wears it on a chain around his neck.

He has read part of his mother’s book, but finds it difficult to see what his family endured as his life hung in the balance.

“I can’t help but feel bad,” he said.

The young man who once lay “at death’s door” now looks ahead to a bright future. He works a full-time job at night and goes to college during the day, studying welding and computer-aided design. He fishes and hunts, backpacks and travels.

But he does not ride bulls.

“I don’t think anyone I know would allow that to happen,” he said with a smile.

Of his brush with death, he said, “It seems like it was a long time ago.”

Asked how he thinks he pulled through the ordeal, he credits faith, family and friends.

“I was very aware of my family being there all the time and how much support they gave me,” he said. “I was also very much in a prayer state all the time.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>