Addison Post laughs and dodges as her dog, Peanut, leaps for the treat she holds high.

“A lot of her doctors call her their little mystery,” says her mother, Rachel Post.

Addison glances through the blond bangs that sweep across her eyes.

“Well, I am a mystery,” the 9-year-old says. “No one ever knows what I’m thinking or what I’m doing. I’m a series of mysteries.”

She grins and gives Peanut the treat.

Playing in her living room and bantering with her mom, Addison reveals little sign of the extremely rare medical condition that has sent her to more than a dozen medical specialists.

Shortly after birth, her parents learned she has oculoectodermal syndrome, a condition that affects her in multiple ways—causing issues with her skin, eyes, bones and digestive system. Fewer than 20 cases have been reported worldwide.

In her nine short years, she has undergone about 30 surgeries and biopsies, plus countless scopes and scans at Spectrum Health Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital. She struggles with the pain of rheumatoid arthritis and the risks that come with immune system dysfunction.

Last year alone, she had 99 doctor appointments.

But even with all the specialized medical care, Addison remains a mystery in many ways to her doctors. What drives her condition? What is the best way to treat it? How can they coordinate her care when it affects so many areas?

To better meet this challenge, her doctors took an unusual step. On a recent morning, two dozen people filed into a conference room at Spectrum Health.

The group included researchers from Van Andel Institute and Michigan State University’s College of Human Medicine, as well as pediatric specialists and staff from Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital.

They settled in for a day of presentations and discussions with one goal: to combine their insights, skills and brain power to help Addison.

Matthew Steensma, MD, organized and led the symposium. As an orthopedic oncologist and scientist, he became involved in Addison’s care in two ways: He performed the surgery to remove benign tumors in her arm and leg bones, and he pursued the research that uncovered the gene mutation at work.

When he first met Addison, he discovered a third connection, as well: He and Addison’s mother, Rachel, went to high school together.

“My heart goes out to Rachel, because her child has this rare disease, and she’s suffering,” he says.

Meeting the original expert

Addison is the second of four daughters born to Rachel and Jon Post, of Hudsonville, Michigan. She showed signs of her unusual condition at birth. She had about 12 blister-like lesions on her scalp. The lesions were aplasia cutis, small spots where skin did not form.

“They actually took her away from me at the hospital,” Rachel says. “They thought she had an (infection) and put her in isolation.”

After a biopsy showed she did not have an infectious disease, the Posts were able to take her home. They immediately began the search for answers.

In addition to the scalp lesions, Rachel noticed Addison’s right eye appeared to have no iris. In fact, a growth had covered the eye.

When Addison was 4 months old, they brought her to geneticist Helga Toriello, MD. The Grand Rapids doctor recognized her condition immediately.

The reason? Dr. Toriello is the one who discovered oculoectodermal syndrome. In 1993, she published the first study about the condition, after noticing similar symptoms in two unrelated boys.

15 specialists

The syndrome affects Addison’s life in so many ways, it has become part of the fabric of her childhood.

Once a month, she spends the day at Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital receiving an infusion of arthritis medication. The pain caused by rheumatoid arthritis can be severe.

“We used to have to carry her down the stairs,” Rachel says.

She also had numerous growths on her eyes, causing the eyelids to become so thick they could barely close. She underwent 16 eye operations to remove the growths.

Benign tumors formed in her right leg and arm bones, causing stress fractures. Although not cancerous, they ate away at the bone and put her at risk for breaks. She underwent four operations to remove them.

Inflammation in her digestive system at one point left her unable to eat. She had a feeding tube for two years. After that, she attended an eight-week intensive feeding program to relearn how to eat food.

By the time Addison started school, her mother had a binder with information on the 15 medical specialists who oversee her care.

“I tell people I am blessed to stay home,” Rachel says. “This is my full-time job.

“Being Addie’s mom is one of the greatest gifts God ever gave me. She is literally a miracle and every day I am just so thankful for her.”

Between medical visits, Addison fits in school and a host of fun activities. She keeps busy with her sisters, Emily, 10, Gabby, 7, and Ciri, 6.

“I like playing,” she says. “I like to ride horses. I like to go swimming and ice-skating.”

And her dog, Peanut, a 1-year-old little bundle of white fur, provides cuddles and entertainment.

But when cold and flu bugs circulate, Addison has to stay home. Three times, a cold or strep throat has sent her to the intensive care unit. She now takes antibiotics daily.

‘The plot thickens’

In 2013, Dr. Steensma began to search for the genetic cause of her condition. With her parents’ permission, he worked with the College of Human Medicine and Van Andel Institute to sequence the DNA in her bone tumor. Bioinformatics experts at the Van Andel Institute analyzed the data, attempting to find a single pair of mismatched DNA molecules out of the roughly 3 billion pairs that make up Addison’s genes.

“We found a mutation in a very, very important gene, the KRAS gene,” he says.

The gene (pronounced K-ras) is one of the most heavily studied genes because of its role in causing cancer.

“But Addison does not have cancer,” he said. There are few reports of cancers among the patients diagnosed with the disease.

The research team then sequenced the DNA for other tissues―bone, blood, colon, skin.

“And then, the plot thickens,” Dr. Steenma says.

The KRAS gene mutation turned up in some tissues, but not others. And it showed up in varying percentages. The blood cells showed no sign of the mutation. About 35 percent of the tumor cells did. The other tissues he analyzed fell somewhere in between.

“This means, at some point, the mutated cells took over the tumor,” he says. “But in Addison’s blood, skin and bone, her normal cells outcompeted the ones with mutations in the KRAS gene. So there’s this evolution of tissue that appears to have occurred in her case.”

Because of this variation, called mosaicism, two people with the same condition could have different symptoms―another reason Addison is unique.

Future zookeeper

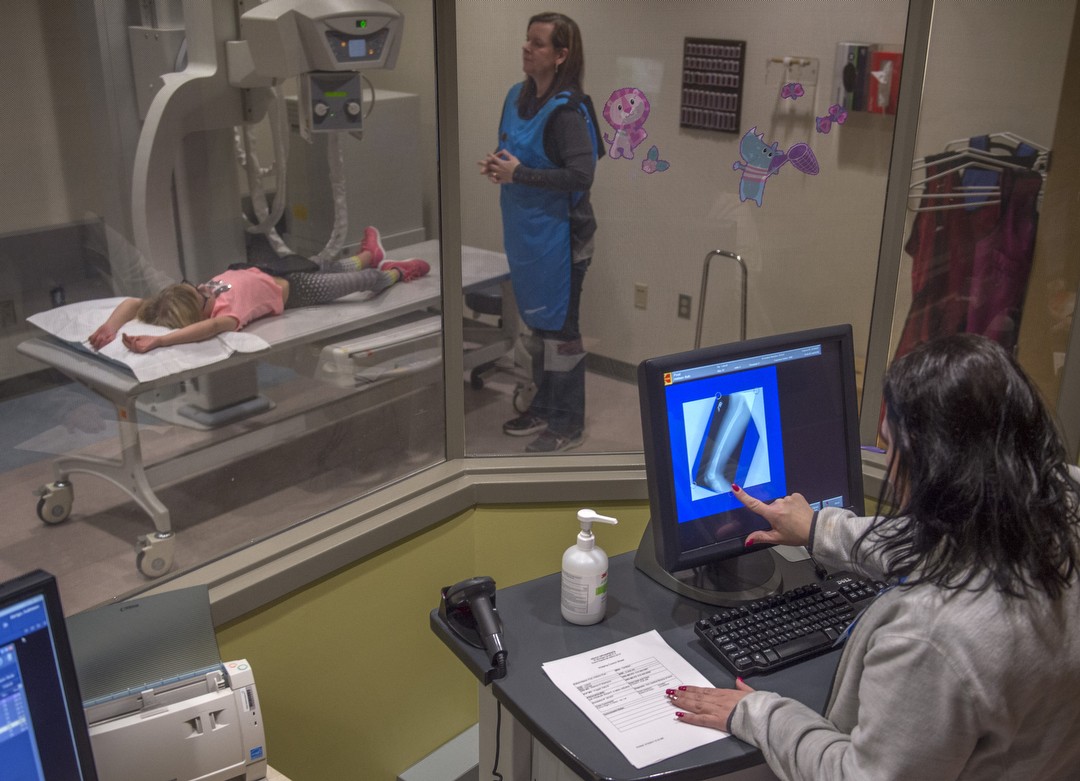

Rachel lifts Addison onto the exam table for an X-ray.

“Mama!” Addison clings to her mother’s hand as she lies down.

Exams are never easy. Today, Addison copes by teasing her mom about getting a new pet.

“How about a gerbil?” she says with a giggle. “A rat? A bear? A tiger? An elephant?”

Rachel shakes her head. “Maybe you’ll be a zookeeper someday.”

Radiographer Kathy Abrigo gently positions Addison’s right leg for the X-ray.

“Mommy!” Addison reaches out. “I love you!”

Rachel bends down and kisses her forehead. “I love you, too.”

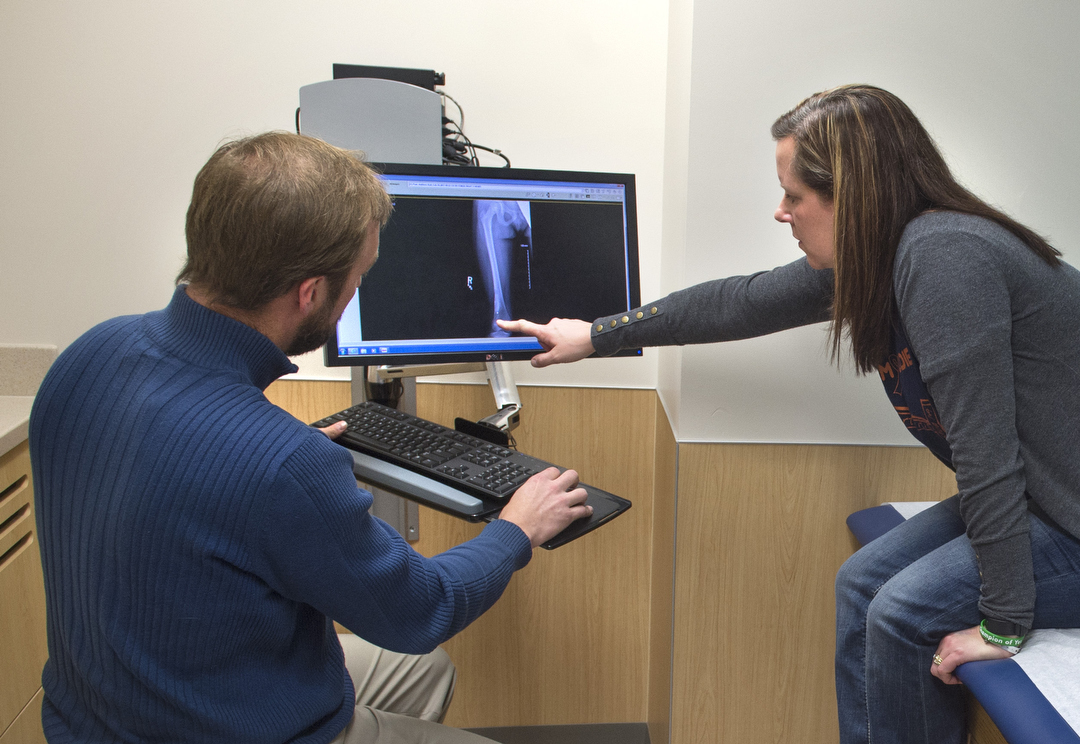

They move to Dr. Steensma’s office. Addison wears pink noise-canceling headphones and watches videos on an iPad as her mom and the doctor talk.

“As far as her bones go, they look great,” Dr. Steensma says, pulling up X-rays on a screen to show benign tumors that remain in her leg and arm bones. “The tumors haven’t changed a bit. Her bone is growing fine. It’s possible her bone can outgrow these lesions.”

They decide to wait two years before taking new X-rays if there’s no change in symptoms.

He updates Rachel on the symposium, which occurred two weeks earlier. Among the key concerns identified was the need to better coordinate Addison’s care provided by the many specialists.

Christina Barton, a nurse navigator with Spectrum Health Medical Group’s department of orthopedics, agreed to take on the role of coordinating medical care and advocating for Addison. She will help to arrange tests and appointments to minimize disruption―so Addison doesn’t have to come in for 100 doctor appointments every year.

The symposium also focused on how to move ahead with research and new treatments. Dr. Steensma will work with other experts, including immunologist Nicholas Hartog, MD, to look for similarities with other syndromes affected by the KRAS mutation and evaluate new treatment options. They doctors will consult with experts at other institutions, as well.

“For Addison’s case, it’s incredibly important that we consider every possible side effect of a new therapy for her disease,” he says. “We are looking for both a safe and effective answer.”

“I like that everyone is going to be working together,” Rachel says. “That will be nice. I just wish there were more answers instead of more questions.”

“I know it,” Dr. Steensma says. “You have my word. We will keep working. Our goal is always to go from discovery to treatment.”

The appointment over, Addison puts away her iPad and slips into her jacket.

Despite the lack of clear answers, Rachel says she appreciates that the doctors, amid the complexities of medical research, focus first on Addison and her quality of life.

“This is my child. She’s not a science project,” she says, and she believes her doctors recognize that.

“It’s not about them. It’s about her,” she adds. “They have been so amazing and invested in her.”

As they walk out the door, Rachel says to Addison, “Did you hear that? You don’t need X-rays for two years on your leg.”

“Yay!” Addison looks up with a smile.

‘I am brave’

In Addison’s room hangs a teal board that proclaims “I am brave.” It displays long strands of colorful beads―more than 500 of them. Each bead represents a medical event―a poke, a procedure, a biopsy, a test.

Rachel bought the sign for Addison at a craft fair to remind her she is a girl of tremendous courage.

“A lot of times, you can focus on how hard it is. But we can also show her she really is an awesome person,” she says. “It’s amazing what she is able to do. It makes me cry a little bit.

“I wish I could do it for her.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

Wow! Tear jerking! I’m so proud to know these beauties. Wow.

Praying for you!

Twylla

For anyone who doesn’t know this family personally, they are the kindest, most humble, God-centered people who bring brightness to any situation. Addie and her sisters were given to Jon and Rachel because they are such amazing parents and just genuinely good people! Thank you for sharing your story!

Thanks for adding that, Jane! We are honored to share Addie’s story.

What a beautiful, brave, special, incredible girl. Prayers for her and her family.

Agreed. She is as brave as she is sweet.

I know this family. Addie and her sisters are all amazing girls. Rachel and Jon are wonderful; so very loving, hardworking, fun, trusting in God to give them strength.

Addy, you are so beautiful… inside and out! Never forget how much you are loved! ❤

“Nurse Kim” – 3rd grade

I would LOVE to make these signs for patients at Helen DeVos! They could be customized to colors and sayings. I could even add the awareness ribbon of any cause.

What a journey you have been on, Addie! We love you and are praying for you, your sisters, and your mom and dad.

Heidi, George, Macey & Maggie

While I’m sure it’s been discussed, would some type of stem cell or bone marrow transplant do anything to help by way of wiping out the immune system she has now and replacing it with that of a donor’s?

Addie, you are a brave, beautiful child of God! You teach me patience, courage and trust. God is using you to teach me how I need to live. At 9 years old, you are a teacher and a preacher for many people! I am praying for you and your precious family. I love you very much, and Jesus loves you best. ❤