A hereditary disease haunts Heather Ramirez. And her family.

After giving birth to her first child 17 years ago, the ghost of ancestors past surfaced.

Sage seemed like a healthy baby boy. Until he wasn’t.

“When he was around 4 months old, he got really sick,” Ramirez said. “He didn’t want to eat, he didn’t want to be touched, he was just sick all the way around.”

Sage presented to the emergency department with symptoms similar to colic. Ramirez’s motherly instinct burned deep.

“I knew there was something wrong with him,” she said. “I told them I’m not leaving until you find out what’s wrong with him.”

Doctors attempted a spinal tap, but couldn’t complete the test.

“At that time, they did an MRI and found a really large blood clot near his spine,” Ramirez recalled. “They had to do emergency surgery.”

New mom. New baby. New fears. Then, more fears.

“While he was in surgery, he bled out terribly,” Ramirez said. “That’s when they tested his blood and found out he had hemophilia. They gave him blood transfusions.

“It was pretty scary. I really wasn’t scared when we had to keep bringing him to the hospital because I know some babies have colic. But I wasn’t expecting the outcome to be (hemophilia).”

Nor was she expecting her infant to bleed profusely.

“He was losing a lot of blood,” she said. “My immediate thought was ‘is he going to make it?’”

She did the only thing she knew to do in that moment of completely helplessness. She prayed. Perhaps harder than she had ever prayed before.

‘It’s going to be OK’

“I was saying ‘don’t let this happen, please don’t let this happen,’” Ramirez said. “I really didn’t think he was going to make it through. But he came out of surgery, they had the blood transfusion going and had him on his factors. They told me, ‘Everything looks like it’s going to be OK.’”

For the moment, anyway. And for that child, anyway. But it wouldn’t be the first time hemophilia became an issue for the Ramirez family.

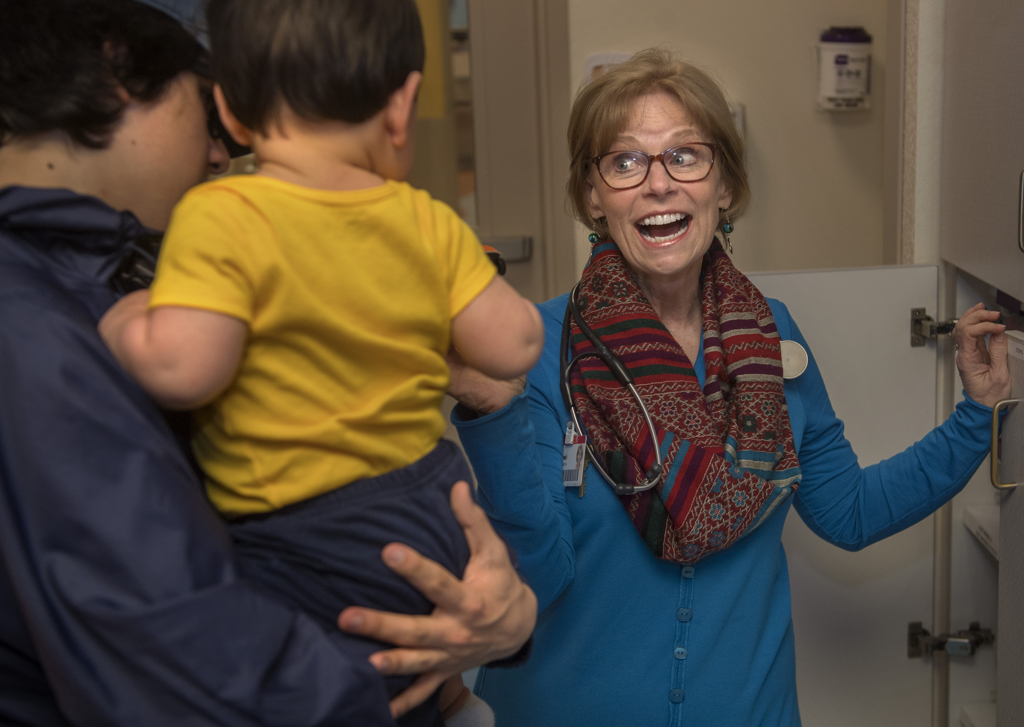

While Sage remained hospitalized, Ramirez met with Spectrum Health Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital hematologist Deanna Mitchell, MD, and the hematology team.

“They were so great explaining what hemophilia was and that it is something genetic,” she said. “They asked if I had any problems with bruising or bleeding. I said, ‘Well, I bruise pretty easily.’ They asked if anybody in my family had this.”

Ramirez thought, then thought some more.

“I was sitting there thinking about it and remembered that my cousin’s son has a bleeding disorder, but I wasn’t sure what it was,” Ramirez said. “We later found out that it was hemophilia, the same type that my son had.”

Ramirez said she learned from doctors that her maternal grandmother likely carried a gene that passed hemophilia along to her offspring.

All in the family

“My mom is a carrier and she passed it on to me,” Ramirez said. “My aunt was a carrier and she passed it to her daughter. That’s about as far back as they can go with it. Genetically speaking, it would have had to have started with my grandmother.”

Hemophilia is carried on the X chromosome and passed along by a woman, although females generally do not develop the condition.

“I always bruised so easily as a kid,” Ramirez said. “And when I get a cut or something, it takes me a little longer to stop bleeding than other people. I was tested through my doctor for my factor (VIII) level, and my level is pretty low, too. It’s not even close to what a normal person’s would be.”

Ramirez said she got an education. A big education, that stretched through her lineage, tracing a dotted line from her maternal grandmother to her children.

“We get out of the hospital and we’re well-informed,” she said. “They were talking about Sage’s whole future, what he could do and couldn’t do. The hardest part was when they have hemophilia and they start crawling and walking around. It’s not just about getting injured. You can have a spontaneous bleed in your body. If these kids have bleeding, sometimes you can’t see it.”

Not always on the outside

But what you feel, as a parent, she quickly learned, is constant fear. Fear not only for what is seen, but for what may be hidden. Fear for what could happen next, when the current moment has barely introduced itself. Fear for her children’s present, and an ever-uncertain future.

Ramirez took Sage to the Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital Hematology Clinic twice each week to receive infusions to help prevent bleeding.

“He was all boy and he got hurt so much,” she said. “Sometimes, it was like we lived there.”

As Sage entered second grade, Ramirez gave her son infusions at home. Then, when he hit age 12, Sage learned to give the infusion treatments himself.

You wouldn’t know he suffers from a bleeding disorder by looking at him, his mom says, but he can’t play football. Or any contact sports. He and his family have to be ever-on-the-ready for any sign of trauma or bleeding.

While Sage was Ramirez’s first experience with hemophilia, he would not be the last.

A year and a half after Sage, Ramirez gave birth to Jacob, now 16.

“They tested him from the cord blood when he was born and he was negative for hemophilia,” Ramirez said. “It made me feel really good, but I thought it might be a problem with them growing up and one can do certain things (like contact sports) and the other can’t because they’re so close in age. But Jacob always respected his older brother.”

More bleeding disorders

Later, Ramirez welcomed her daughter, Kayla, to the world.

“Only in rare cases girls can have it, but I wasn’t worried,” Ramirez said.

Symptoms interrupted her calm.

“She started to bruise really badly when she was a toddler,” Ramirez said. “That’s when she got tested for bleeding disorders. We found out she has another bleeding disorder called Von Willebrand disease.

Von Willebrand disease is a bleeding disorder caused by low levels of clotting protein in the blood. It affects about 200,000 people nationwide.

The problems could run deeper.

“We don’t know 100 percent, but we’re pretty sure she’s also a carrier for hemophilia,” Ramirez said. “She just got tested. We’re supposed to find out by June.”

For males with hemophilia, they cannot pass the gene onto their sons, but they will pass the gene onto all of their daughters, who will be carriers.

“For Sage, his sons cannot have hemophilia,” Ramirez said. “It ends with him. If Sage has a son, he will not have hemophilia, but if he has a girl, there’s a 100 percent chance of her being a carrier.”

Ramirez’s daughter Sophia, 8, has also been tested to determine if she’s a carrier. Those results are also expected in June. Dr. Mitchell tested Sophia for Von Willebrand disease last year and her levels were borderline. She will be tested again at the end of May.

Then, there’s Micah. Born on June 15 last year, he carries on the hemophilia legacy.

“When he was born they tested his cord blood,” Ramirez said. “He does have hemophilia. I was OK with it. They’ve come so far with treating hemophilia. I get nervous if they would ever be in an accident, just as any parent would. But it’s so treatable now.”

The news seemed almost inevitable, certainly not unexpected.

For now, Micah may seem safe. For parental purposes, he’s like a potted plant. He’s not crawling. He’s not walking. But threats arise when they least expect them.

“He’s had two bleeds already,” Ramirez said. “One, he got just from receiving his vaccinations. He had a bleed in his thigh. The last one we had was on Easter. In church, he was kicking the pew in front of us, not even that hard. Later that night I gave him a bath and his foot was so swollen and bruised. I called the hematologist on call and went to the ER.”

A history with hemophilia

Ramirez is more comfortable this go-around. She knows what to expect after a history of hereditary hemophilia.

“With Sage, there were a lot of ‘I don’t know if I should bring him in to ER’ moments,” Ramirez said. “Now, I know what to look for. On Easter, when I saw Micah’s foot, I knew we had to bring him in. This time around, I feel like I’ve got the hang of it.”

Dr. Mitchell said it’s been a pleasure working with Ramirez and her family for almost two decades.

“They are wonderful kids,” she said. “Their mother has demonstrated incredible compliance and care for their bleeding disorder. The kids have accepted their bleeding disorders and make the best of their lives.”

That includes attending The Hemophilia Foundation of Michigan’s bleeding disorders camp near Muskegon, Michigan, every summer. All the children attend.

Dr. Mitchell said it’s not rare for one family to have so many children affected by hemophilia or other bleeding disorders.

“Each of Heather’s sons would have a 50 percent chance of inheriting the X chromosome that does not code for normal factor VIII,” Dr. Mitchell said. “She has one son who does not have hemophilia and two that do have hemophilia. With each pregnancy, it is like a flip of the coin. Her daughters would also have a 50 percent chance of being a carrier for hemophilia.”

Dr. Mitchell said Sage and Micah are doing very well, much to the credit of Ramirez, and later Sage, being diligent about factor VIII infusions.

“Sage is a healthy 17-year-old who attends school daily, works and plays some sports activities,” Dr. Mitchell said. “Their prognosis is good.”

And the prognosis could get even better.

“Gene therapy has recently been demonstrated to be effective and will likely be an option for Sage and Micah in the next few years, which will likely eliminate the need for pokes or infusions,” Dr. Mitchell said.

The danger of the disease remains real.

“Males with severe hemophilia will bleed with minimal or no trauma into joints, muscles and even vital organs, including the brain,” Dr. Mitchell said. “They are treated with factor VIII (infusions). The factor products are very expensive, but allow the boys to grow up without joint disability or life-threatening bleeding.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>