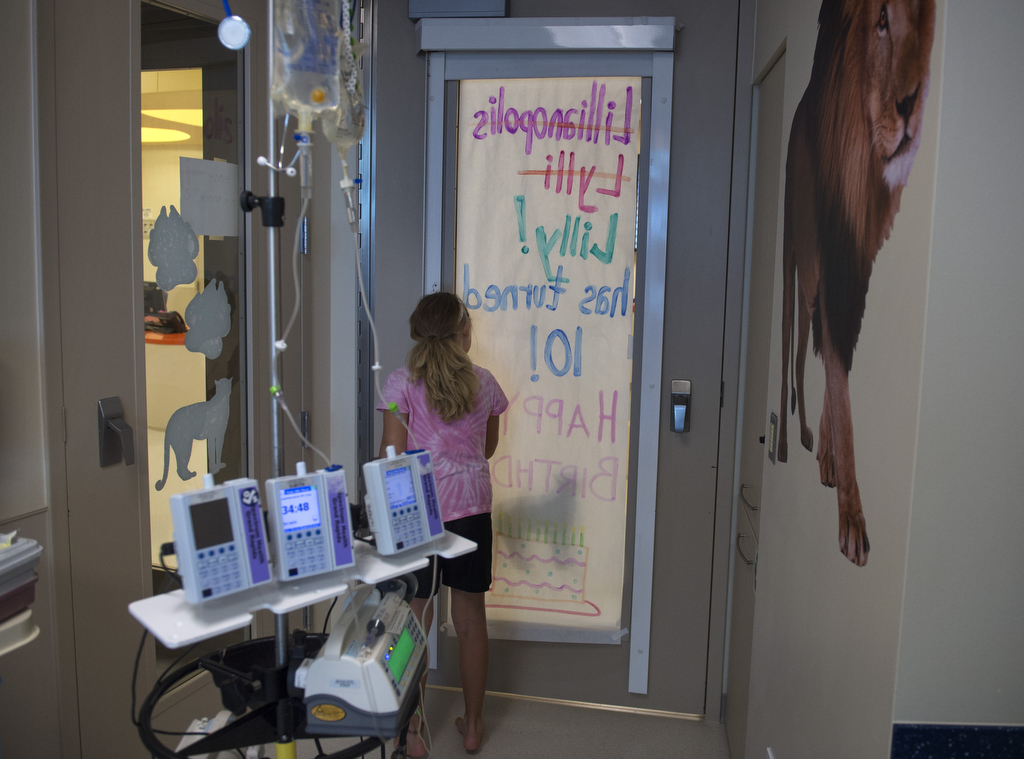

Armed with games, activity books and an iPad, Lilly Vanden Bosch wore a confident smile as she walked into her room at Spectrum Health Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital last week.

Anticipating her arrival, volunteers had affixed huge decals of cougars and African lions to the walls. A stuffed cat perched on her bed, which was covered with a fleecy pawprint throw.

“I’m a little nervous,” she admitted. “I’ve been waiting for a long time.”

But mostly, Lilly was eager to get started on the journey to wipe out her severe aplastic anemia once and for all.

The feline-themed room will be home to Lilly and her mom, Meg, for the next several weeks as Lilly undergoes a bone marrow transplant and then as doctors monitor her blood counts to see if the transplant effectively annihilates Lilly’s autoimmune disease.

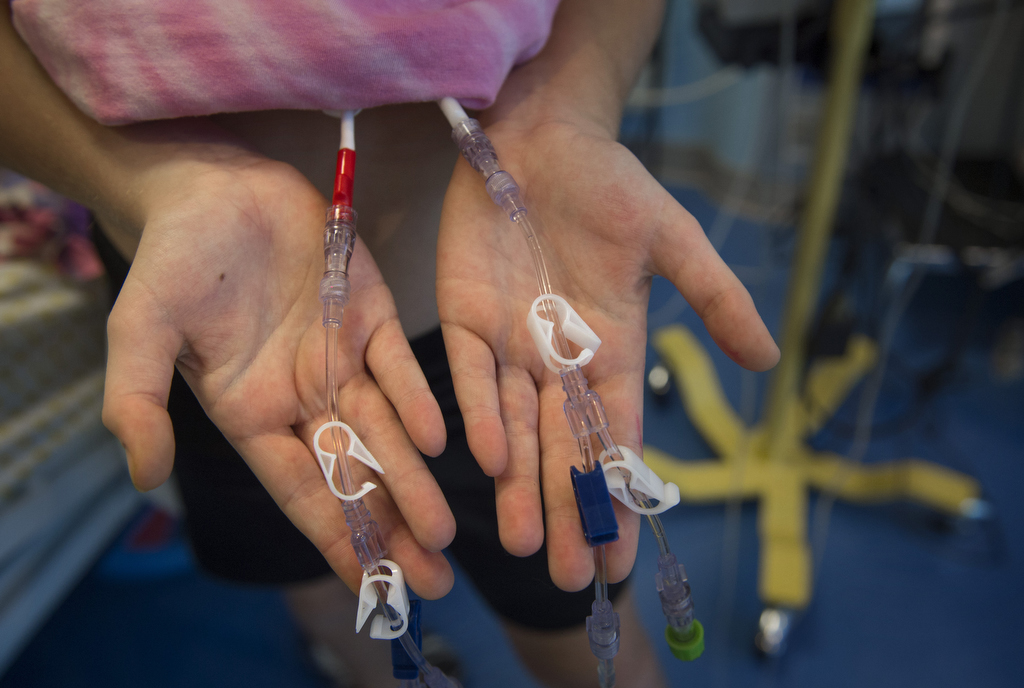

During this time, Lilly will be strictly quarantined in her room of big cats, Xbox games and Skype. Her parents, big sister, aunt and grandma have been designated as her chief caregivers. To curb the chances of Lilly contracting a virus or other infection, visits from others are discouraged.

Anyone who does enter her room, including doctors and nurses, must wear surgical masks.

Transplant preparation

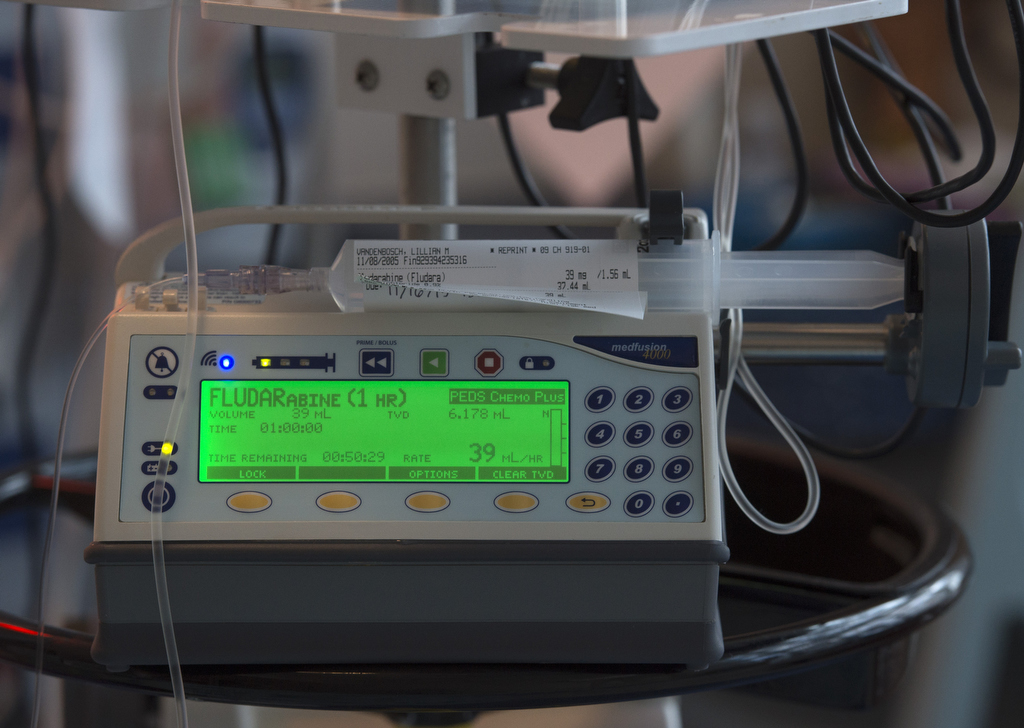

For the 11 days leading up to the bone marrow transplant, now scheduled for Friday, Nov. 27, Lilly will undergo chemotherapy and radiation.

This conditioning regimen of chemo and radiation won’t be as intense as that administered to most leukemia patients, said Ulrich Duffner, MD, director of clinical services for the Pediatric Blood and Bone Marrow Transplant Program at Spectrum Health.

As a result, Lilly will be less likely to experience damaging side effects, such as organ damage, infertility or malignancy.

The idea is to completely suppress her immune system so it won’t attempt to fight off the new bone marrow she’ll receive from 4,000 miles away.

The goal is to get Lilly’s body to accept the stem cells contained in the new bone marrow, Dr. Duffner shared.

“The immune system tries to reject foreign ‘non-self’ cells, so Lilly’s should have no power left to reject the donor cells,” he said.

This immune suppression is necessary to prevent the donor’s cells from attacking their new home—Lilly’s body.

“Such an attack would result in graft versus host disease, a possible complication of the procedure,” Dr. Duffner said.

In the meantime, Lilly will be defenseless against any sort of infection. And that’s a risk that will last for many months. Post-transplant, Dr. Duffner anticipates that a new immune system will form. It will be made from the donor’s cells, which will accept and protect Lilly. Then, about six months after the transplant, no additional immune supression drugs should be needed.

‘Giving thanks’

The fact that the transplant will take place right around Thanksgiving doesn’t go unnoticed by Lilly or her parents.

“I think it’s cool,” Lilly said. “I’m obviously going to be giving thanks because the donor is saving my life.”

While Lilly is engaged in her treatment—knowing the names of the drugs and the timeline of when she will receive them—she admitted the lengthy hospital stay is “kind of boring.”

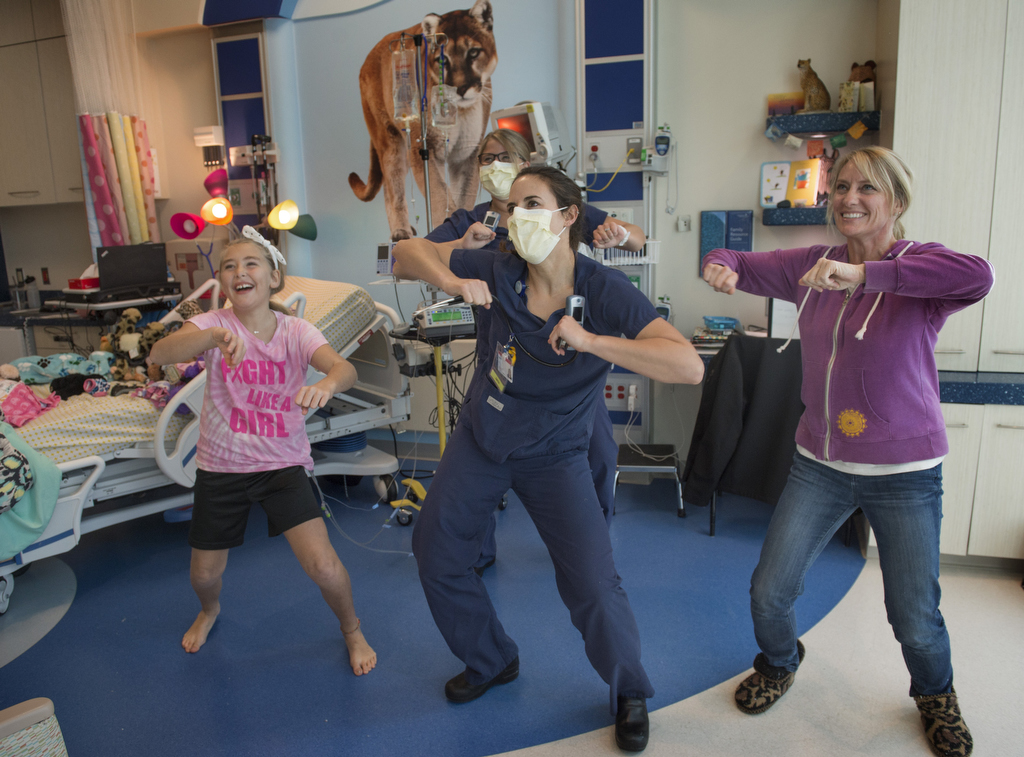

Thanks to infusions of blood and blood products, she still feels pretty good, so she’s spending time riding an exercise bike in her room, Skyping with her teacher and classmates at Saint Stanislaus Catholic School in Dorr, Michigan, and competing with her mom and caregivers for bragging rights as top scorer in her Xbox dance games.

“I won three times with my mom,” Lilly declared on her third day of hospitalization.

During quieter times, Lilly thinks about her friends and how she misses sleeping in her own bed and cuddling with her fox terrier, Julio. She’s worried that the chemotherapy might make her feel sick and that she is likely to lose her thick blonde hair.

“But I have a lot of hair so I’m hoping I won’t lose all of it,” she said with her trademark optimism. “And we brought along a lot of cute hats in case we need them” her mom, Meg Vanden Bosch, added.

Ask Lilly if she wonders why aplastic anemia chose her and she grows more somber, looking to her parents for support.

“They don’t know the cause so it’s weird that I got it,” she said finally. “But there has to be a reason. Maybe I’m being called to be a hematologist?”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>