Late one night, Tyrone Bell sat on the edge of his bed, ready to get a good night’s sleep before going to work in the morning.

His left hand began to tingle. The strange feeling spread from his fingertips up his arm.

“It’s like it fell asleep, but I wasn’t lying on it,” he said. “I stood up to try to walk it off.”

His left leg didn’t seem to cooperate. His steps came awkwardly. He realized he had seen someone walk like this before—his mother, after she had suffered a stroke.

Bell was only 35 years old, but the symptoms seemed too similar.

He called to his roommate, Sigmund Strickland, and told him he was having a stroke. As he spoke, he noticed his speech became affected, too.

“I was trying to say ‘bro,’ but I couldn’t pronounce the ‘R,’” he said. I kept saying ‘Bo. Bo, help me.’”

Strickland picked Bell up, threw him over his shoulder, carried him downstairs to his car and drove to Spectrum Health Butterworth Hospital.

“I was scared, but I was so calm,” Bell said. “I don’t know why. I didn’t freak out or panic or anything.”

To have a stroke out of the blue like that, it was scary.

Two weeks later, he sat in a bed at the Inpatient Rehabilitation Center of Spectrum Health Blodgett Hospital as he talked about his stroke and his drive to regain control of the left side of his body.

From the day he arrived at the rehab center, he impressed his therapists with his upbeat, determined attitude.

“I can’t cry over spilled milk,” he said. “What is done is done. All I can do is try to get better. I feel if I keep a positive attitude about it, I’m going to get better faster.”

Quick treatment

Bell thinks his stroke was linked to his diabetes, which he has had since age 26.

“I must have got too comfortable and got reckless with my diet,” he said.

But he still couldn’t believe a stroke could affect someone his age.

“I never, ever thought I would have a stroke,” he said. “I’ve always been so healthy and so active. I barely even catch colds. To have a stroke out of the blue like that, it was scary.”

He works in a factory, goes fishing with his brother and watches drag races. He likes to barbecue and he is helping his brother build a food truck.

When Bell arrived at the Butterworth Hospital emergency department, he received the clot-busting drug tPA, said Nadeem Khan, MD, a vascular neurology physician.

Act FAST

Use FAST as an easy way to identify the most common symptoms of a stroke. Get help immediately if you observe any of these symptoms:

F – Face drooping

A – Arm weakness

S – Speech problems

T – Time to call 911Source: The American Heart Association

A CT angiogram did not show a large clot that could be removed. Instead, Bell had suffered a lacunar stroke—which occurs when blood flow to the small arteries in the brain is blocked.

Lacunar strokes account for up to 20 percent of all strokes, according to the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

Even for those who suffer a lacunar stroke, research shows the clot-busting drug leads to improved outcomes in the long run, Dr. Khan said. Doctors give it to patients who are treated within 4.5 hours of suffering a stroke.

He praised Bell’s decision to seek help immediately after noticing his first symptoms, so he could receive the medication.

“I think that made a huge difference,” Dr. Khan said. “A lot of time, patients see right-side weakness and they think they will sleep it off and it will get better.

“Time is brain. That is why we do a lot of patient education and family education on common signs and symptoms of a stroke.”

Stronger by the day

Three days after Bell arrived at the emergency department, he transferred to the Inpatient Rehabilitation Center.

On that first day in rehab, he wondered what was in store. He couldn’t move his left leg or his left arm.

“I couldn’t even hold myself up when I was sitting,” he said.

In physical therapy, he began relearning to move his leg, to stand and walk. In occupational therapy, he learned new ways to manage daily tasks with just his right arm, while also regaining function of his left arm.

“Every day I wake up, I feel stronger and stronger and I get more confident,” he said.

On a spring afternoon two weeks after his stroke, he walked through a hospital courtyard, past blooming flowers and a bubbling pond. He navigated the cobblestones with help from a four-pronged cane—good practice for walking on uneven surfaces.

“We knew from Day 1 that he would do really well,” said physical therapist Linda Rusiecki as she walked beside him. “Tyrone has a few factors going for him.

“He’s lean (so he has less weight to support while standing). He was very active and mobile before his stroke. And he has had such good family support. That always makes a big difference.”

And because Bell is younger than most stroke patients, his brain has greater neuroplasticity, she explained. His brain can rewire itself more readily, changing and adapting after an injury.

“I feel like the therapists make a big difference, too,” Bell said as he sat in his wheelchair to rest. “If you’ve got good therapists, you’ll recover well.”

Rusiecki smiled.

“Look at that,” she said. “You walked about 100 feet.”

‘It’s juicing your muscles’

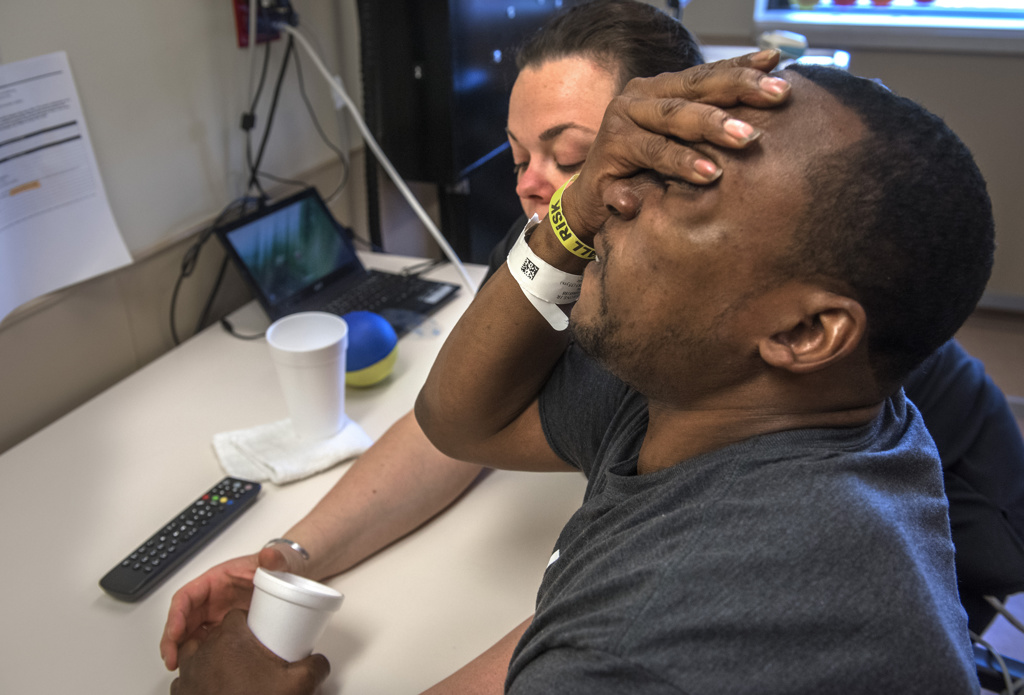

In occupational therapy, Bell sat on a therapy table and performed exercises with his left arm, reaching to the side and forward. He swung the arm from the shoulder, trying to hit a target with his hand.

“I can move my arm, but I can’t move my hand at all,” he said. “Not my wrist, not my fingers.”

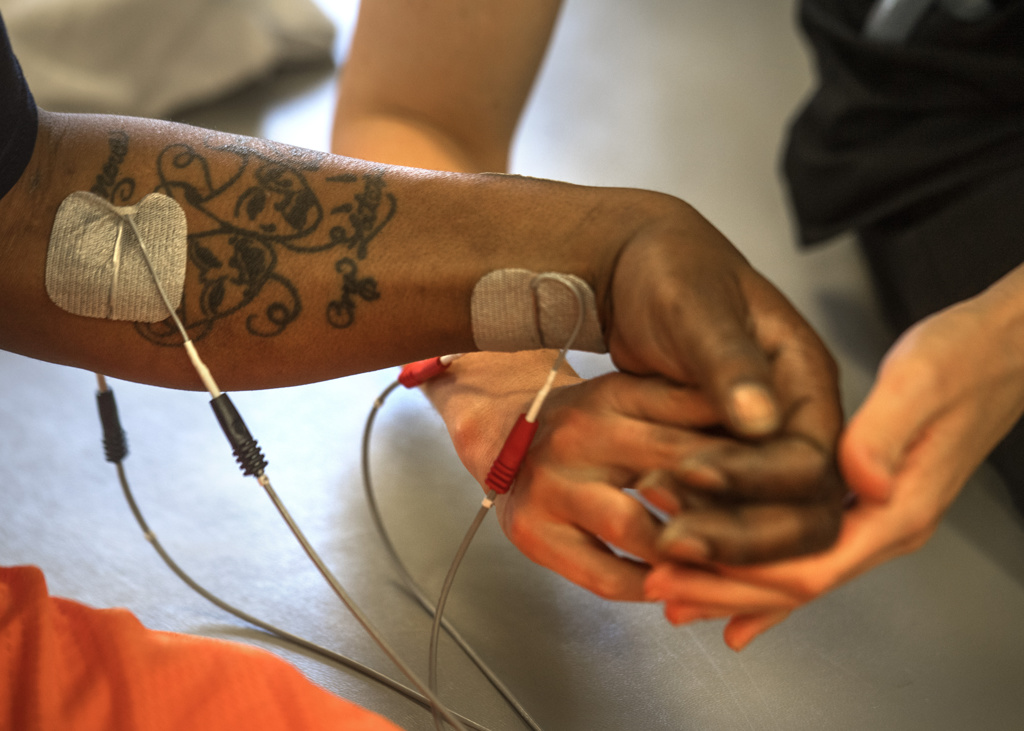

Occupational therapist Holly Omiljan used electrical stimulation to boost his arm function.

Through electrodes placed on the front and back of his forearm, a device delivered electrical shocks that allowed his hand to open and close. With the electrical help, his fingers curled in to grasp a towel, then uncurled to drop it in a pail.

Bell also uses electrical stimulation to aid the movements of his foot and leg as he walks.

“It feels so weird at first,” he said. “But once you get used to it, you realize it’s juicing your muscles.”

In the hallway outside the therapy gym, he practiced raising his left arm to tap the handicap-accessible button that opens the door. He tried twice while sitting in his wheelchair but couldn’t quite reach the square target.

He stood up and leaned on a cane for a better angle. He raised his arm and brought his hand solidly onto the button. The door began to open, and Bell laughed.

“I’ve been trying to do that for so long,” he said.

I feel confident that I am going to fully recover.

Back in his room, next to the balloons and cards from his daughter and siblings, he rested after a full day of therapy.

He explained his willingness to share the story of his stroke and recovery. Early in his stay at the Inpatient Rehabilitation Center, he met a man whose wife had experienced a stroke. The man told him about the great progress she made with therapy.

“That gave me a whole lot of hope and motivation right there,” he said. “If his story helped me, then maybe my story can help somebody else and motivate them.”

With each step forward, he becomes more optimistic about life after a stroke.

“I feel confident that I am going to fully recover,” he said. “I feel pretty good about it. I’ve got a lot of love and support. That makes it easier, too.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>