Follow the sound of laughter at the Grand Rapids Home for Veterans, and you’ll wind up bumping into Daniel McCarthy, 61.

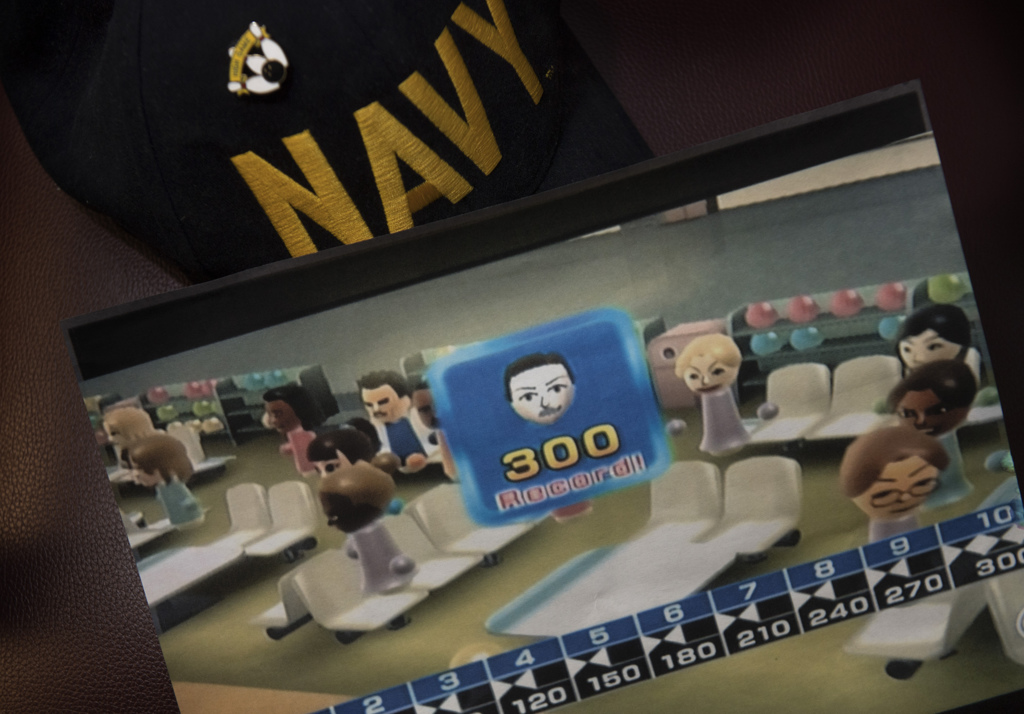

Seated in his wheelchair, tipped back for a perfect view of the television screen that displays a Wii game system, he painstakingly manipulates the game controller with trembling hands.

His hands shake with tremors from the Parkinson’s disease that has ravaged his body if not his spirit.

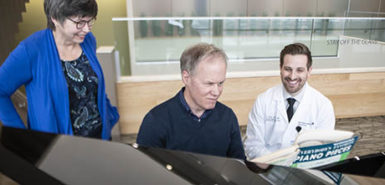

Brian Spyker, a Spectrum Health Hospice social worker, sits beside him to help with the game and chuckle at McCarthy’s jokes—some of which are meant to give him a ribbing as he plays along.

They are playing a Wii bowling game, competing for a perfect score of 300. It’s an online, computerized version of bowling, and it’s a challenge for even experienced bowlers.

With a grin barely hidden beneath his bushy mustache, McCarthy makes it known he has beaten Spyker at the game. Several times.

“It’s true,” Spyker says.

A perfect score

But then McCarthy pauses to tell his story, and Spyker leans in to help clarify when McCarthy’s voice weakens from the strain.

“I’ve bowled a perfect score of 300 on this system,” McCarthy says. “It’s one of my proudest achievements.”

He was introduced to the computerized game at the Veterans Home, and he was immediately hooked. Prior to learning it, back when his body was still strong, he had bowled for 35 years, often on bowling leagues and in tournaments, with an average score of 179, but a record score of 289.

“I’m very competitive,” McCarthy says. “I’m very determined.”

Spyker nods in agreement. “He plays every day.”

“My first Wii game wore out, just like me,” McCarthy smiles. “So I got a new one.”

A string of challenges

Parkinson’s has not been McCarthy’s first health challenge.

Born in South Bend, Indiana, in a family that included eight boys and one girl—“Dad wanted to create a baseball team,” he joked—he and the “team” moved to Saginaw, Michigan, where he graduated from Douglas McArthur High School in 1976.

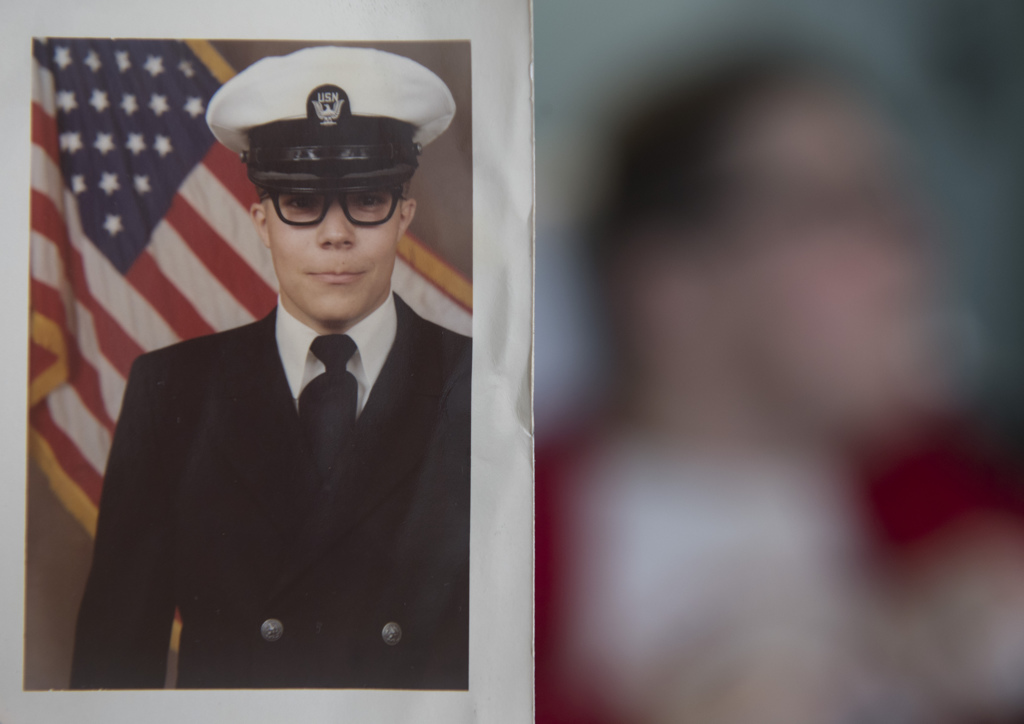

“I joined the Navy then, and I was an operations specialist in radar,” McCarthy says.

He served in the Navy, in San Diego, California, for five years on the USS Leahy. After completing his military service, he remained in California for several more years.

“I didn’t have an occupation,” he says. “I had jobs.”

McCarthy also met a woman, became engaged, but later broke it off. Another engagement came to the same end.

He struggled with money problems and sank into depression.

“I tried to commit suicide, but I heard a voice that told me—don’t do it,” he says.

Part of the plan

McCarthy returned to Michigan, and he returned to school, earning his college degree in human resource management at Baker College in Flint.

In his 30s, however, health problems began to come up, one after another.

At age 39, doctors diagnosed him with diabetes. A few years later, he beat kidney cancer. A kidney was removed as well as his gall bladder. A few years more, and he had triple bypass surgery. Arthritis ate away at his bones, causing more pain.

In 2011, McCarthy learned he had Parkinson’s disease, a degenerative disorder of the central nervous system. Symptoms include shaking, rigidity, difficulty with walking and movement in general.

Growing despondent once again, McCarthy contemplated ending his life a second time in 2016. He couldn’t take the pain anymore.

McCarthy took what should have been an overdose of pills, but still—his body wouldn’t give up. He realized it wasn’t his time and God, he says, wouldn’t let him go. The experience strengthened his faith.

“It was hard for me to learn to accept help,” McCarthy says, but he did learn.

“Daniel is very motivated,” Spyker says. “He’s a fighter.”

McCarthy has even found love again. He checks the time for when Jeanne, his love, will come by again to visit him.

“She’s a beautiful woman, and I love her,” he says, and it’s clear that this time he’s not joking. “We met when she would come by to visit her brother here at the Home. She could have loved anyone, but she chose me—she says because I make her laugh.”

As the passing days take their toll on McCarthy’s body, he remains strong in his conviction that life is worth living—and that he was wrong in trying to bring it up short. He sees life now as a gift.

“One should never give up,” he says. “Stay positive. God has a plan for each one of us, and I’m living mine.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>