Daniel Hannapel has been through a lot in his first 20 years of life.

He’s had three heart-related surgeries tied to a rare condition known as Marfan syndrome.

The condition has prevented him from participating in many of the sports he had hoped to enjoy, but it hasn’t changed his positive outlook—nor has it weakened his desire to give back to people who have helped him along the way.

Marfan syndrome is a rare connective tissue disorder that affects about 20,000 people each year in the U.S., said Jason Slaikeu, MD, RPVI, a Spectrum Health vascular surgeon.

It affects the integrity of connective tissues that normally support the body’s vital organs and structures.

Marfan syndrome can be hereditary, although in Daniel’s case it arose from a rare, random mutation, according to doctors. Daniel could still pass the incurable disease on to his future children.

Symptoms of Marfan syndrome may vary from person to person, but the most serious side effects of the disease can affect blood vessels in the heart and lead to weakened arteries.

People diagnosed with Marfan syndrome are often taller and thin, with long arms, legs, fingers and toes.

Daniel, 20, a sophomore at the University of Michigan, has some of those basic characteristics.

Doctors first diagnosed him with the condition in 2013, at age 12, when he went to the hospital for a dislocated shoulder.

They also detected a heart tremor.

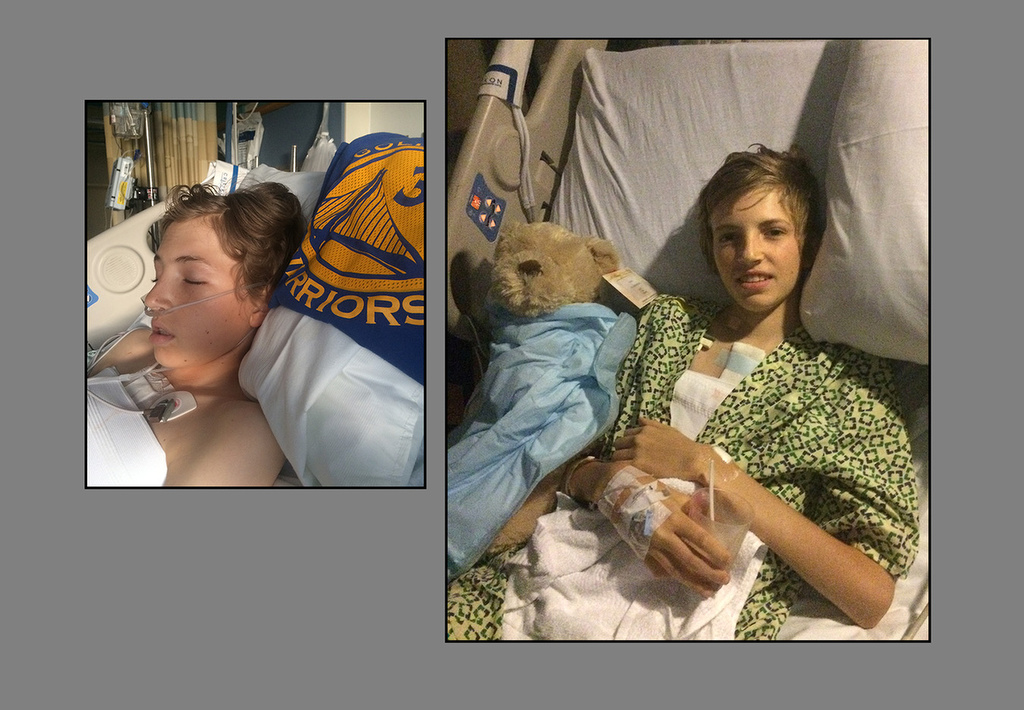

In 2015 he underwent his first surgery, a heart valve repair. The operation wasn’t easy, as doctors had to surgically break 12 of his ribs and reconstruct his sternum.

Almost one year to the day, in 2016, Daniel collapsed with what ended up being an undiagnosed abdominal aortic aneurysm.

Dr. Slaikeu was the surgeon on call that day who performed the emergency surgery when Daniel’s aneurysm ruptured. This experience created a unique relationship between doctor and patient.

High hopes

Daniel went several more years without any major incidents.

In January 2021, however, he underwent a third heart surgery, this time at a hospital outside Michigan.

Dr. Slaikeu phoned Daniel on the evening of surgery to check on him.

“Throughout the whole recovery process, Dr. Slaikeu called me every day to check up on me,” Daniel said. “I appreciated the time he took out of his busy day to see how I was doing. He is an amazing doctor and surgeon and his bedside manner is remarkable.”

The doctor has returned the admiration in kind.

“I’ve been so impressed with him and his family ever since I’ve known them,” Dr. Slaikeu said. “He is an incredible young man—resilient, caring individual. And he’s also smart, ambitious and extremely personable.”

Daniel’s diagnosis during his teen years came as a blow, for as a young boy he had high hopes in participating in contact sports. He was a natural athlete and his world was sports.

But instead of letting Marfan syndrome dictate his course, he found satisfaction in activities that offered plenty of challenges and rewards—activities that proved less stressful on his heart.

At Thornapple Kellogg High School in Middleville, near Grand Rapids, he played golf and sang in the honors choir. He devoted careful concentration to his studies and ultimately graduated in the Top 10 of his class.

Now at the University of Michigan, he has founded an intramural golf club. He’s involved in the men’s glee club, which performs nationally and internationally.

Most importantly, he remains ever grateful for the support he received from friends, family and the community.

And he wants to pass along the goodness.

As a pre-dental student, he’s tutoring elementary children in Ann Arbor through his fraternity. Daniel is also involved in a hospice program started during the pandemic.

He feels he can still do more.

He’d like to establish an organization to help children with cardiac issues.

“I am in a unique position to help guide pediatric patients experiencing cardiac issues,” Daniel said. “I’ve been there and I know what they are feeling. I know how scary it can be.”

Giving back

At a young age, Daniel learned about the importance of helping others. He follows in the footsteps of his parents, Beth and Eric Hannapel, both orthodontists who have instilled in their four children the importance of giving back.

Eric volunteers at the Spectrum Health Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital oral cleft palate program in Grand Rapids. He’s part of a team of doctors and dentists who develop treatment programs that often involve jaw surgery, bone grafts and other major procedures. Beth is also heavily involved in community service.

The Hannapels’ philosophy for their children: “Choose a career you enjoy, work hard at it and then make giving a part of your life.”

Daniel has taken it to heart.

And he knows that, to help others, he must also pay close attention to his own health.

There’s no cure for Marfan syndrome, but the goal is to avoid future heart problems by way of regular exams and testing.

Amid it all, Daniel has learned to thrive.

“Marfan has many physical limitations that come in varying severity, but as I’ve gotten older, I’ve found that the mental aspect has been more challenging,” Daniel said. “Before I was diagnosed, I was a typical teenager enjoying life in my carefree world and that all changed.”

And now?

“I’ve created a positive mindset through the support of my friends, parents, brother, amazing doctors such as Dr. Slaikeu and the entire community.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

He is an amazing young man from an amazing family! Keep reaching high Daniel you will succeed and conquer! Very proud of you and love you very much! Larry n Betty Fischer

I remember Dr. Slaikeu fondly from his residency in colorectal surgery several years ago. (I tried to dissuade him from moving on to vascular surgery, but he followed his passion!) Always positive and completely genuine, he was as skilled with people’s emotional needs as with their surgical challenges. I found it inspiring to read Daniel’s story, particularly when I realized he had attended Thornapple Kellogg High School, where our three sons also graduated. All the best to Daniel and to Dr. Slakieu!

You are so inspirational and as I read your story over, over and over it reminds me of how special life is and that we each are given an opportunity to aspire to guide, help and to educate our friends, neighbors and to show our caring and love. Your friend, Linda

What a gift to be part of your families friend base and your journey. This article depicts the very essence of Daniel’s being. I was always in awe of his mature, loving kindness at such a young age that was only enriched as he became a young man. So proud of your resilience and sharing your gifts Daniel! Thank you to the medical team that continues to care fir this rare condition and special man. A big shout out to Eric, Beth and the rest of the Hannapel tribe moving through such difficult times with love, positivity and consistent gratitude. Love you! Keep the soul light shining Daniel!