A clear liquid dripped from Benny Boes’ IV pole as he and his wife, Elise, reminisced about their trip to San Diego three years ago.

“We rented a Ford Mustang convertible, and we did the Pacific Coast Highway,” Elise said.

“And all the towns along the way,” Benny said. “That was fun.”

They hope Keytruda, the experimental drug slowly infusing into Benny’s bloodstream, will give them more time to travel. More time to enjoy each other and their two sons.

More time to live life to the fullest, even as Benny battles a brain tumor.

“Any extra time I can get,” Benny said. “If I can get an extra year out of it, I’ll be pumped.”

The experimental treatment almost didn’t happen. It took advocacy from a cancer doctor and coordination with a drug company and insurer to bring the small bag of immunotherapy agent to Benny’s treatment room at Spectrum Health Cancer Center.

The Jimmy Carter connection

Every three weeks, Benny spends a half-hour getting an infusion of Keytruda. It’s also known by its generic name, pembrolizuma, or pembro. Benny’s not sure what effect it will have on his glioblastoma―but he’s glad he at least got the chance to see.

It’s a pretty amazing thing that they are actually going to mimic the clinical trial for us.

Keytruda was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for treatment of melanoma and lung cancer. It came into the public spotlight last year when former President Jimmy Carter took it for metastatic melanoma―and subsequent scans showed no sign of cancer.

Researchers now are testing it against glioblastoma, an aggressive brain tumor that is considered incurable. The median survival for patients is 15 to 16 months.

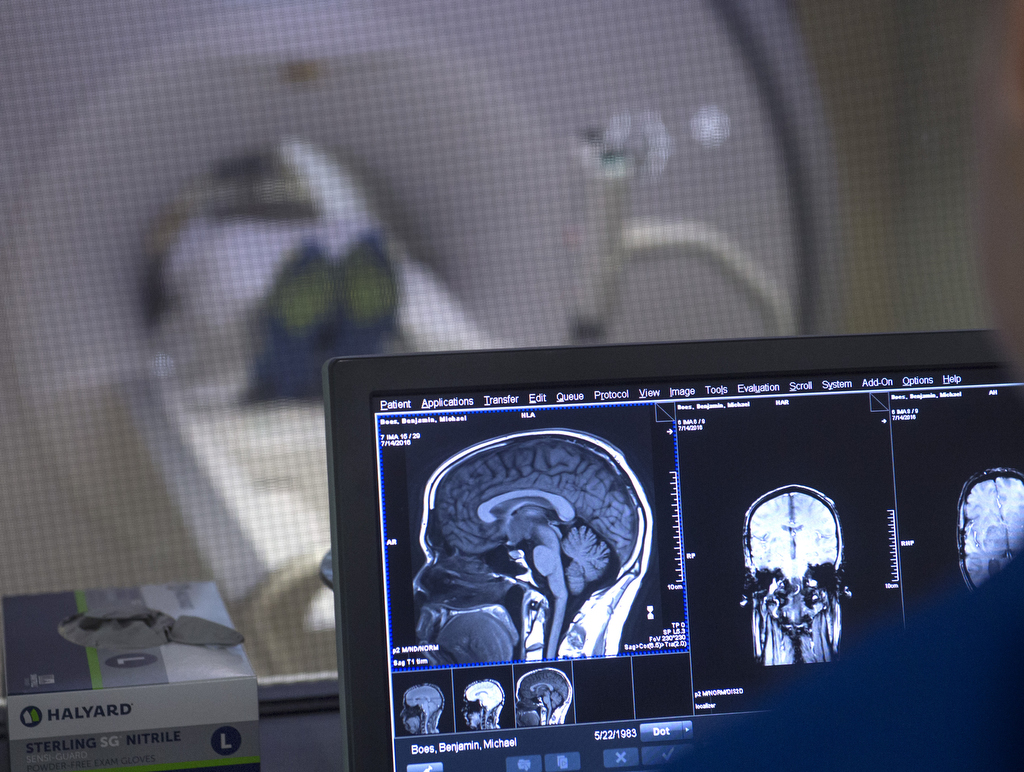

Boes, 33, was diagnosed with glioblastoma in April. Since then, he has undergone surgery, chemotherapy and radiation therapy. He looked into clinical trials in hopes that an experimental treatment would boost his odds of defeating the tumor or at least prolong his life.

Keytruda is a genetically engineered, antibody-based medicine designed to work with the body’s disease-fighting system. It blocks proteins that prevent the immune system from attacking cancer cells.

“The immune system as a whole is down in glioblastoma,” said Wendy Sherman, MD, Boes’ neuro-oncologist. “The idea behind the drug is it’s essentially driving the immune system to recognize the cancer as it would a virus and attack it.”

Research into Keytruda and glioblastoma has found early evidence that it “has some activity in some people,” Dr. Sherman said.

If that’s sounds vague, it’s because there are not enough results yet to be more specific.

“It’s still very, very early,” Dr. Sherman said. “The big trials that are really going to tell us anything are currently ongoing.”

The hope offered by immunotherapy, however, is crucial for Boes, because chemotherapy is not particularly effective against his type of brain tumor. His glioblastoma, called non-methylated, includes enzymes that detect the damage caused by chemo and repair the tumor cells.

Boes tried to get into a clinical trial for Keytruda at two sites. A study in Chicago was not enrolling new patients at the time. And one in Detroit would have required him to relocate there for his six-week course of radiation. He and Elise decided the disruption in daily life would be too hard on their sons, Callan, 7, and Stuart, 4.

For a while, I had a feeling that hope was denial. But I’m starting to change my mind about that.

Dr. Sherman sought to provide the drug to Boes in Grand Rapids, outside of a clinical trial, but modeling its use after the trial’s protocol. She contacted Merck, the maker of Keytruda, to see if he could receive the drug under compassionate use.

Merck agreed to provide the drug at no charge. Boes’ insurer, Priority Health, agreed to cover the infusions.

An additional benefit to the treatment is that it causes few side effects, Dr. Sherman said. In boosting the immune system, it can cause skin rashes and colitis, but medications can be used to minimize them.

“It’s nice to be able to offer something more,” Dr. Sherman said. “This could be potentially beneficial and is a relatively low-risk therapy.”

“It’s a pretty amazing thing that they are actually going to mimic the clinical trial for us,” Benny said. “It’s such a ray of hope for us.”

Planning the next move

The day after his third Keytruda infusion, Benny returned to the cancer center early in the morning. He lay on a table as radiation beams targeted what remained of the tumor in his brain.

It was his last radiation treatment.

Afterward, he and Elise met with Gwen Leegwater, RN. Benny grinned and held up the colorful “graduation certificate” he received.

“I got my official recognition,” he said.

Leegwater thanked Benny and Elise for the lessons she has learned from them.

“We’ve got to take each day one day at a time,” she said. “I’ve seen that in you guys. One day at a time.”

Elise talked about their next move.

“We just want to pick up and go,” she said. “Take the kids to the Grand Canyon. To Moab. To Arizona. Let’s go to Seattle and Portland. Let’s just go everywhere.”

A week later, Benny sat on his couch, picked up his smart phone and recorded a video to update family and friends. With the grueling days of chemo receding into the past, he felt stronger every day.

“I’m getting really hopeful again,” he said. “For a while, I had a feeling that hope was denial. But I’m starting to change my mind about that. I’m getting really hopeful about how everything is going.

“We’ll see, but it’s a journey and I’m feeling pretty good about it right now.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

My late husband had same brain tumor in 1977. He opted for immunotherepy after chemo and radiation didn’t work. Within 6 monthd he was cancer free and remained that way for almost 4 years. Unfortunately he released in 1981 and succumbed to the . The quality of life on immunotherepy was so improved out was amazing. Now, his regiment wasn’t a genetically made antibody, it an autologous vaccine made from his own immune system. There were other things such as cleansing body and boosting his immune system with mega-vitamin therapy. Immunotherepy has been in research since 1950 or so. He amazed oncologists with his remission and they did implement some of the boosting therapies along with chemo radiation. I have no idea how that worked for them. Congratulations for getting some real help. I’m excited for you and I pray this works wonders for you. Immunotherepy is the future for helping to conquer this terrible disease.

Glioblastoma doesn’t seem to be a rare form of cancer among Virtnam vets and their children. Finally the Vetrans Administration recognising it as a service connected disease. Stephen King eluded to it in one of his books set in the 1970’s stating something such as how can the Government not recognise this as service connected when so many of my friends are dying.from it. I have to believe it’s much more prevalent than what our medical community seems to believe.

Benny & Elise, I have been praying for you everyday. I was just going to message Marilyn to ask for an update. God is on the move. I’m expecting a good report.

NEVER give up hope! I am a 20 year cancer survivor and I’d like to think attitude is very critical. Keep your positive attitude strong!