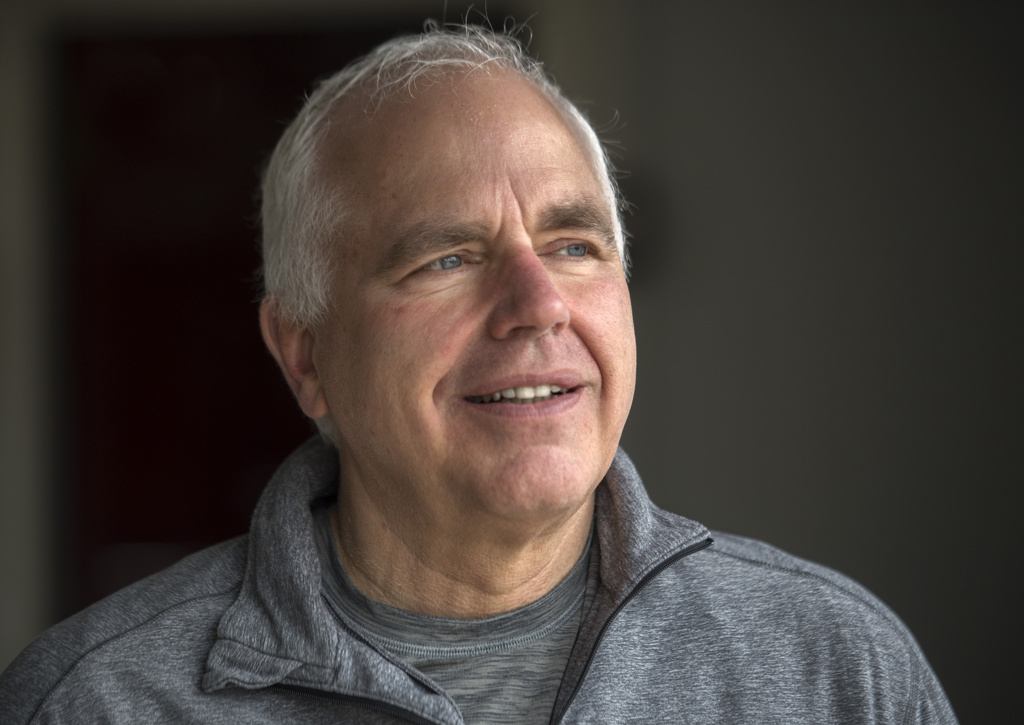

Bob Kingma, 69, grew up surrounded by healthy foods at his family’s business, Kingma’s Market, on the southeast side of Grand Rapids.

Leafy greens, root vegetables, strawberries, blueberries and more were his constant companions.

Later, when he took over the business, eventually moving it to Plainfield Avenue on the northeast side of the city, his health remained a priority.

He walked. He biked. He didn’t shy away from manual labor.

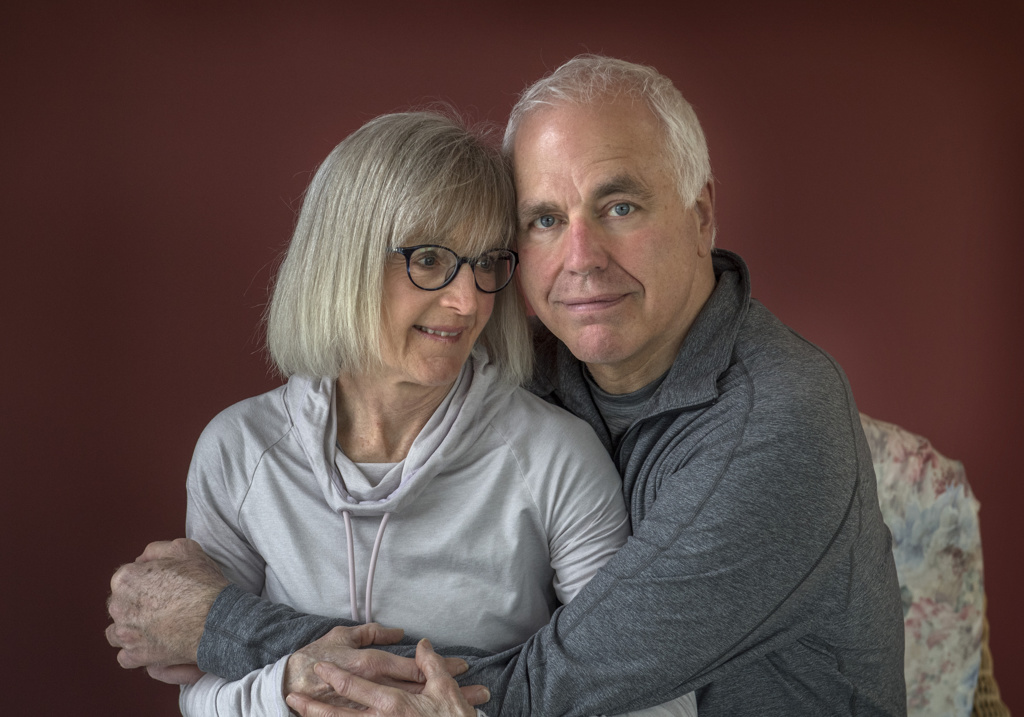

In June 2019, he and his wife, Kae, completed a two-and-a-half-week journey around Israel.

“We went all over and hiked around,” he said. “We went all over the country.”

A few days after returning home, life took a haunting turn.

Kingma and Kae went out to eat with another couple to celebrate Kae’s birthday.

“I was feeling well,” he said. “I went to bed and woke up in the middle of the night because I had to use the bathroom. When I got into the bathroom, the wall seemed to shift back and forth sideways. I’ve never had anything like that. It just got worse.”

He sat down on the toilet seat. He couldn’t focus his eyes. He couldn’t cry out for help. His body swayed.

Thankfully, the toilet behind him and walls on both sides helped him stabilize, keeping him from crashing to the floor.

Kingma attempted to utter his wife’s name, a single consonant. He failed.

“I couldn’t talk,” he said. “Things were not well. I remember focusing and trying to get out, ‘K.’ I made a guttural tone. She came in. I couldn’t stand. She went downstairs to get a cane. That didn’t help.

“She said my mouth was sagging and I was drooling,” he remembers. “I could hardly focus. I was swaying back and forth. She said, ‘I think you’re having a stroke.’”

Kae dialed 911 and explained her husband’s condition to the dispatcher, providing critical information that indicated he might be having a stroke.

The dispatcher instructed her to leave the front door unlocked.

Within minutes, an ambulance arrived.

“I can visually picture everything that night,” Kingma said. “There were two gals in the back of the ambulance. I remember the ride to the hospital in the middle of the night. The streets were empty. My mind was fully aware of what was going on, but I couldn’t sit, stand, walk or talk. My head was slumped down.”

Even though he could barely move, his mind moved to a frightening future.

Would he ever walk again? Talk again? Would he ever again embrace Kae and their children and grandchildren?

“There was terror of living like this for the rest of my life,” he said. “It was kind of a broken prayer I couldn’t even mouth.”

‘I could feel him threading’

At Spectrum Health Butterworth Hospital, the health team wheeled Kingma into an operation room.

“There were people in gowns waiting,” he said. “They were all gloved up. It was the stroke team. They lifted me onto the observation table and started hooking me up to all kinds of stuff.”

Kae arrived just as the stroke team finished a CT scan.

They identified the problem—a left vertebral artery occlusion.

Spectrum Health neurosurgeon Paul Mazaris, MD, prepared for the procedure. He would insert a catheter through an artery near Kingma’s groin to reach the clot at the back of his neck.

“We went in with a small catheter, which is a long skinny tube, and opened up the vertebral artery with a small balloon on the end of the catheter,” Dr. Mazaris said. “This restored blood flow to his brain that was starving for oxygen.”

Kingma said he could feel the catheter being threaded through his body.

“One of my arteries in the back of my neck wasn’t functioning and the other was pretty thin,” Kingma said. “I could feel him threading. All of a sudden, control of my fingers returned and I could start talking again. They were asking all kinds of questions and I was answering quickly.”

The turnaround stunned everyone, including Kingma.

“Everything returned—my fingers, voice, body commands,” he said. “I could move my fingers and toes. They couldn’t believe it. It felt good to have it back.”

Kae remembers the feeling of relief that swelled over her, like a calming wave.

“The doctor came back and said, ‘He’s very fortunate, we got it,’” she said. “He seemed totally fine. There was no permanent damage at all. I don’t notice any difference in him compared to before the stroke.”

Kingma credits the stroke team’s quick response with saving his life.

“They acted so fast,” he said.

Still, more work remained.

Kingma would need to undergo another procedure to help prevent blockages from returning.

‘Very fortunate’

The following week, surgeons replaced Kingma’s neck arteries with more viable arteries from another part of his body. This provided his brain a thicker and more assured blood supply.

“I asked how soon I could get back to hiking and biking,” Kingma said.

The doctor suggested he take it easy for a week.

So he did.

He felt a bit tired that summer, but otherwise he had no limitations.

And he’s since taken on life’s other adventures.

“I’ve been hiking up and down small mountains in the wilderness and heat,” he said. “Kae and I do a lot of biking. The prompt treatment saved my brain. I have no residual effects whatsoever. Nothing.”

He sold Kingma Market about six years ago. He now spends some of his time as an associate chaplain at the Kent County Jail.

It’s all been a wild ride, Kae said.

“It was kind of crazy,” she said.

She and her husband count their blessings—their children, grandchildren, travel adventures. Good health.

They’re grateful for the speedy response from health teams that day.

“I kept thinking if this had happened when I wasn’t home, he could have died,” Kae said. “He got to the hospital right away and they were right on top of it. They were ready and waiting for him before he got there and they knew exactly what to do.

“That’s what saved him. We were very fortunate.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>