Brenda Bristol’s art pieces contain curious twists and swirls, a sense of making seemingly incongruent pieces come together as a whole.

Feathers, pine cones, peace signs, Scrabble tiles. Bold and blazing colors arch perceptively on canvas, perhaps more a conversation than a piece.

If there’s any good that came from a horrific car crash on March 5, 2007, it’s this—Brenda is expressing her creative side, something she rarely did prior to the traumatic brain injury she suffered when she lost control of her car on icy roads en route to her job as a residential instructor for Hope Network.

She lives at the Spectrum Health Neuro Residential Program on Kalamazoo Avenue in Grand Rapids, Michigan.

‘A blur’

Her recollections of the accident are vague.

“I was on my way to work and hit black ice,” said the red-haired, blue-eyed 40-year-old who sits in a wheelchair. “A cop that knew me identified me.”

Brenda’s younger sister by three years, Sara Babcock, an RN at Spectrum Health, said Brenda lost control of her car on Morrison Lake Road and was struck by another vehicle.

While checking for a patient in the emergency room, Babcock saw her sister’s name on the ER roster. She immediately recognized the birth date. She rushed there.

“It was a blur of asking questions, answering questions and consenting to procedures,” she said. “Once I knew the severity of her accident I called my mom and told her she needed to come.”

Brenda was in a coma, medically-induced, for about a week, then remained in a coma for roughly another 11 weeks.

“It was very hard when they turned off the sedation and she continued to remain comatose,” Babcock said. “As a nurse and the only medical person in the family, I was the go-to for answers and it killed me to not have one for why she wasn’t waking up.”

When Brenda did wake up, it wasn’t as the person her family once knew. She has trouble speaking, difficulty thinking, a hard time expressing herself.

‘It’s beautiful’

Brenda spent time in various rehab facilities before settling into Spectrum Health’s residential rehabilitation center. She uses a wheelchair for mobility in the residential home.

It’s there that she and other residents spill their feelings onto canvas during the weekly Expressive Arts program, led by program coordinator Ranae Couture.

On this winter weekday, Brenda is adding pink and blue hues to a diamond-shaped, three-dimensional piece she has named “Flying.” It’s full of texture and dimension, with 1-by-3-inch tiles, twine and a kite tail.

Babcock said it’s through her sister’s art that her personality shines through.

“It’s beautiful, original, and bits of her old self,” Babcock said. “Brenda was never really an art type of gal when she was younger. She was more into music and being a social butterfly. I see a lot of the old her when she talks about her art.”

But her art comes as a natural expression.

Couture, an art coach mentor for these patients who are re-imagining their lives, describes Brenda’s specialty as “mixed media using found objects.”

“I try to collect all different stuff for her,” Couture said. “She picks the colors and placement.”

It’s a way for them to be expressive, to feel joy and have purpose and hope. …They can be free. It’s exciting when you see breakthrough moments.

They’re popular pieces, as are most created by brain injury patients during the Expressive Arts program. They sell for $30 to $100 in the on-site “Thumbs Up” gallery during the annual art show and during regular 9-5 studio open hours.

The program residents sell about 150 pieces a year, according to Couture. Proceeds are split between the resident and the purchasing of the studio’s professional-grade art supplies.

“I’ve done more than this, I’ve done a bunch,” Brenda said, surrounded by paintings and mixed media creations.

Wearing a denim smock smeared with yellow, pink, white and green paint stains, Brenda propels herself forward in her wheelchair. A loud crinkling noise erupts as she rolls over a blue tarp that serves as a drop cloth in the ground-floor studio. She pulls herself up to the art table where she soon will be joined by four other residents.

Expressive Arts focuses on art, but often includes, poetry, storytelling, music and dance. On this day, Couture plays Michael Jackson and AC/DC tunes on her CD player. Brenda and the rest of the patients in wheelchairs sing and rock along to the music as they work on their painting projects.

“It helps the brain and it helps residents be alert and engaged,” Couture said. “Brenda likes country music.”

No matter what the skill level, or the brain-function level, Couture, who considers herself a “facilitator of creative expression,” said the goal is to give residents the freedom to express themselves through art, at a time when so many other forms of self-expression may have been shut down due to brain injury.

For some, that just means working up enough strength to put paint brush to paper.

“If they just make one little mark, it’s a great day,” Couture said, as she mixed up red and white paint to form a pleasant shade of pink.

But make no mistake. These artists, despite their injuries, are creating some awesome work. More than 30 of their paintings and sculptures have been part of ArtPrize. They’ve compiled a popular calendar. Other paintings are framed and hanging in homes throughout the region.

As Brenda works on her piece, resident Steve Howell paints clay with an Irish-kind-of-green as Couture speaks. Robin Pierce swoops and swirls lines on poster paper with a magenta Sharpie. Jorge Sanchez, who sometimes paints with his toes, eyes his abstract orange, yellow and green painting. At table’s end, Shannon Dever cuts fabric pieces.

‘I can be me’

Brenda dips her brush into the pink that Couture just mixed and massages the brush against the 3-D tiles of “Flying.”

She paints with her left hand. Her right hand, the dominant one, hasn’t worked since the car crash.

“Good job, Brenda,” Couture tells her. “Wow, that really made a difference. Think you should add another color in there?”

Brenda chooses light blue. Couture mixes the paint.

It’s like this most every week in Expressive Arts. Mixing, mingling, conquering and creating. The goal is not a masterpiece, although there are plenty of those hanging on the studio walls. The goal is mastering a moment.

“It’s a way for them to be expressive, to feel joy and have purpose and hope,” Couture said. “For some, it’s a way for them to express their feelings when they can’t in any other way. It’s a safe place. They can be free. It’s exciting when you see breakthrough moments.”

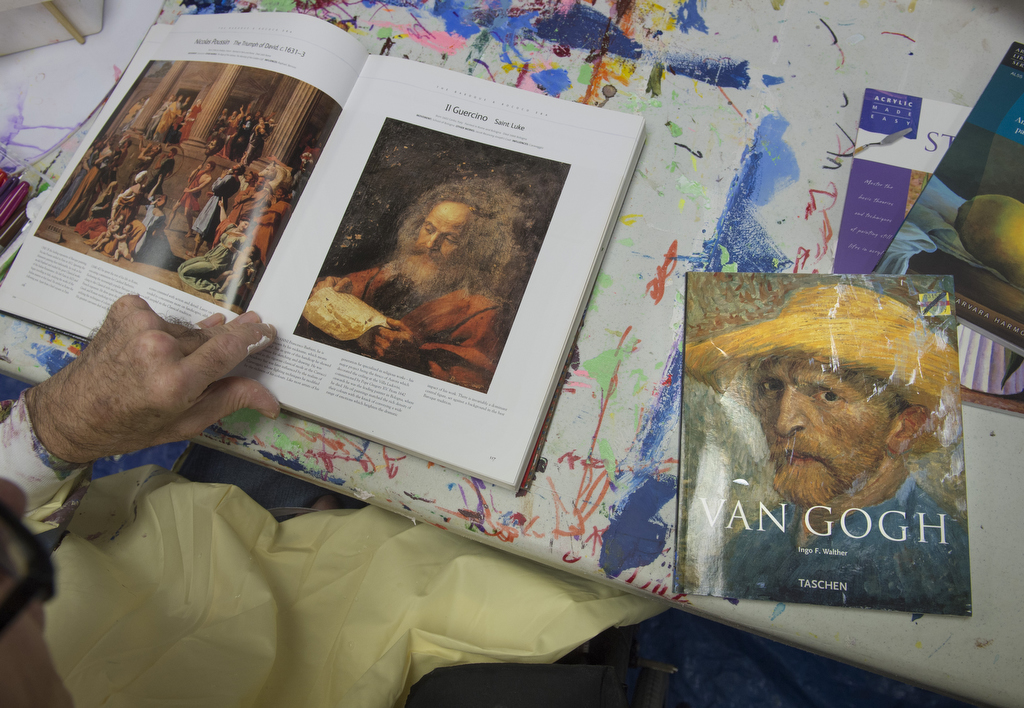

They study the masters—Van Gogh, Picasso and others. But the real person they’re delving into is themselves, sometimes reaching deep enough to touch the person they were before traumatic brain injury erased much from their life’s canvas.

With the swish of a brush, a stroke of color, there’s somehow a glint of remembrance in their eyes.

“I can be me,” Brenda said as she poked her brush into the paint. “I can just be myself.”

Couture sees the progress. It’s not just in the pigment choices. It’s in the person, whether that person actively paints, or just stares at a blank canvas.

“You have to never give up on them,” Couture said. “Build on their strengths. Help them find their way in the creative process so they can become confident with their unique style of expression and this will be healing.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>