“Don’t get too attached.”

Debra Peck’s parents heard that warning as they held their newborn baby girl for the first time.

Their daughter had a serious heart defect. She would not live long, a nurse said. Don’t get too attached.

Of course, her parents did. Her whole family did.

Sixty years later, Peck is still living. Still deeply attached to her large, supportive family. And she hopes to continue to survive, to keep proving that grim prediction wrong.

I have a will to survive. I’m going to keep going and fight.

Peck recently became the second person in the U.S. to receive an innovative life-saving heart device.

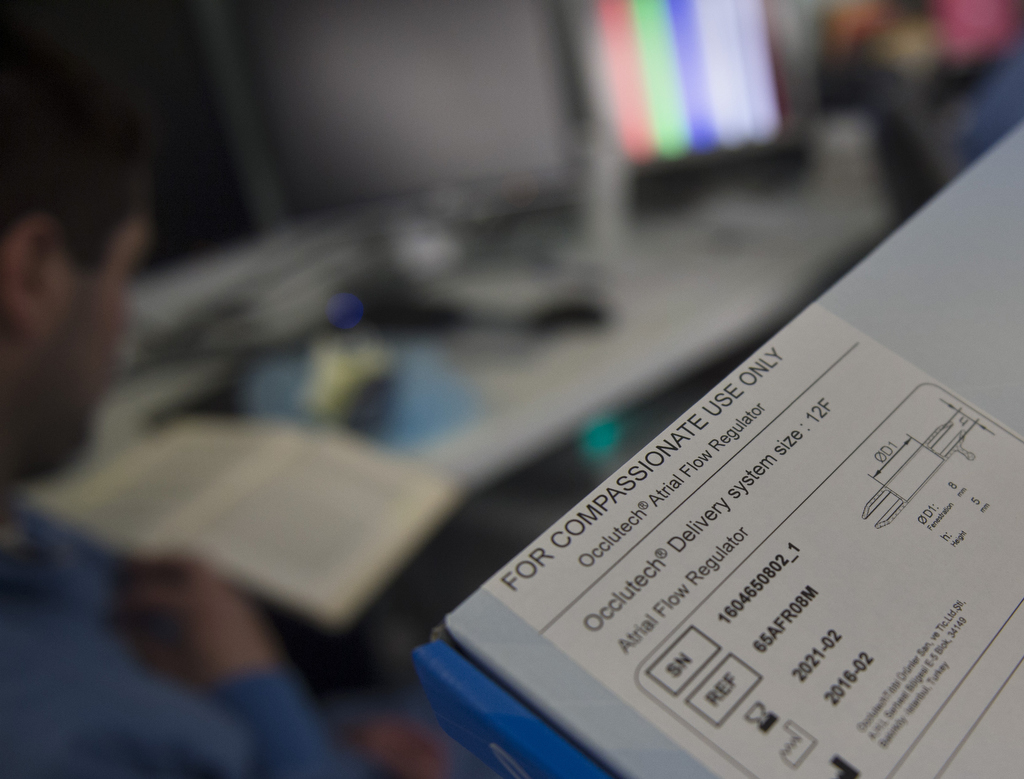

Joseph Vettukattil, MD, co-director of the Congenital Heart Center at Spectrum Health Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital, had to get special permission from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration so Peck could get the device, called an atrial flow regulator. Dr. Vettukattil was involved in developing the device while at his previous institution in the UK. The device is designed to help extend the lives of those suffering from heart failure and give them better quality of life.

That fits with Peck’s goal.

“I have a will to survive,” she said. “I’m going to keep going and fight.”

She hopes this treatment option will give her more time to enjoy life with her siblings. To travel. To play with her dogs at her home in Muskegon, Michigan. To serve on her church’s altar guild. To finish cross-stitching the Christmas tablecloth.

Her family believes in her, said her sister Sue Waggoner. She has watched her soft-spoken sister defy the odds many times.

“She’s got a stubborn streak,” Waggoner said fondly. “When she puts her mind to something, she carries it through.”

‘She always looked so fragile’

Waggoner was 7 when her little sister was born with “blue baby syndrome.” The same chamber of the heart sent blood to both the body and to the lungs―which meant not enough blood was sent to the lungs to be oxygenated.

Peck spent most of her first two years in the hospital.

“Her fingers were purple. Her lips were purple. Her feet were purple,” Waggoner recalled. “She was just a skinny little thing. She always looked so fragile.”

The Peck kids tiptoed around the new baby, careful not to make her cry. If she became upset, she turned purple all over.

As a toddler, Peck underwent surgery to get a shunt. That improved blood flow to her lungs, but she still struggled. Her fingers remained blue, a sign of the lack of oxygen in her blood.

“After the first surgery, they said she probably wouldn’t live to see her teens,” Waggoner said.

The family―which grew to include six children―adapted to Peck’s activity limits throughout her childhood.

Her older brother, Greg, carried her piggyback during games of tag. When she started school, he carried her to the bus stop. An uncle gave the family a shopping cart and they padded it with pillows, so she could ride in comfort after she outgrew a stroller.

By the time Peck turned 35, progress in treating heart disease opened up new possibilities. In 1981, she had a porcine valve implanted in her pulmonary artery. She noticed a difference immediately.

“I looked at my nails and said, ‘I got pink fingernails,’” she said.

She could take long walks. She planted flowers and did yard work. She could stay outside in the winter for more than a brief 10 minutes.

In 1999, surgeons replaced that valve with a new one.

A new solution

Peck now lives with her younger sister, Amy. Both parents have passed away.

About three years ago, Peck became sick with what she thought was the flu. Eventually, she learned she had right heart failure. A doctor told her nothing more could be done for her.

Peck then sought treatment from Dr. Vettukattil. He initially tried to treat the heart failure with medication, but Peck’s condition continued to deteriorate.

Her kidneys began to fail, and her liver stopped working. As an infant years ago, Peck got hepatitis C from a blood transfusion, so she was not considered a candidate for heart transplant.

Dr. Vettukattil suggested trying the atrial flow regulator. He has placed it in one other patient in the United States. There is currently a clinical trial in Europe testing the device, but a trial is not yet open here in the U.S.

“I don’t think she could have survived much longer,” Dr. Vettukattil said. “This was a last resort. This was just to see if she could go back and live near-normal quality of life for a bit longer.”

The regulator is a springy stent, made of nickel titanium, about the size of a nickel and with a central opening. Dr. Vettukattil delivers it through a catheter and places it in the wall between the right and left atrium, the upper chambers of the heart.

This reduces pressure in the right atrium―which in turn relieves pressure on the lungs.

The mixing of blood in the right and left atrium means the blood pumped to the body has less oxygen―but there is more blood going to the body. The patient may be slightly blue, but less in danger of a sudden collapse or organ failure, Dr. Vettukattil said.

“It’s not a cure. It is a palliation,” he said. “It may help them survive longer.”

Breathing easier

A multi-national effort brought the atrial flow regulator to Peck. After Dr. Vettukattil received permission from the FDA for a one-time emergency use procedure, the device was fabricated. A Swiss-based company, Occlutech, manufactured it in Turkey and shipped it from Sweden.

It arrived at 7:45 a.m. May 4, the day of Peck’s procedure.

In the catheterization lab at Spectrum Health Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital, Dr. Vettukattil placed the device in Peck’s heart. Almost immediately, the blood flow from Peck’s heart to her body increased by 28 percent.

The next day, Peck noticed her skin was pinker and she could breathe easier. Over the next couple of weeks, she recovered strength and her failing organs rebounded. She looked forward to visiting family members and enjoying the sunshine outdoors.

“She is such a delightful person,” Dr. Vettukattil said. “She doesn’t complain. She takes it all in stride. Every week she survives, as long as her quality of life is good, it is a great success for us to support her.”

Peck said her lifelong struggle with congenital heart disease has taught her patience, as well as gratitude for life’s blessings.

“It doesn’t pay to complain too much,” she said. “I have great support from my family. When I need something, they are there.”

She and her older sister talked about the predictions made so many years ago when she was born. It was hard to imagine then the medical progress that would occur, that could help keep her heart pumping.

“She showed them,” Waggoner said.

Peck nodded.

“I’m still here.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>