Fred Nelis stood alone outside the Plaza de Toros de La Malagueta in Malaga, Spain, his heart awhirl with emotion.

What a journey.

As the late afternoon shadows gathered, his thoughts turned briefly to the coming week’s competition, then to the friends and family who had trekked to this stretch of sunny Europe to watch him compete.

Sunday, June 25, 2017. Exactly three years and seven days since his heart transplant at Spectrum Health Fred and Lena Meijer Heart Center.

Now here he stood, an ocean away, readying for the opening ceremonies of the World Transplant Games, a competition that would pit him against athletes such as Japanese powerhouse Chikara Wakamatsu, one of the swiftest swimmers he’d ever encountered.

In that moment, Nelis grew quiet as he focused on the one person who had, above all others, made this journey a reality.

The same person he focused on each morning in the past three years, every time he looked in the mirror and saw the surgical scars on his chest.

Nelis decided he would dedicate his first medal to his anonymous heart donor.

Let the games begin

The biennial World Transplant Games attracts athletes from across the globe.

Amid the ferocious competition, of course, there’s a hearty dose of camaraderie and celebration. The athletes share a common bond of organ transplant, their stories brimming with inspiration and fortitude.

Nelis is no different in this regard.

Doctors first diagnosed him with a heart condition in his late 30s. As a lifelong athlete drawn to competitive sports—swimming, foremost—his good health allowed him to avoid invasive treatment for more than two decades.

“I tried to out-swim and outrace Father Time,” Nelis said. “I tried to stay physically strong and enhance my possibility of surviving, but in the back of their minds everyone with cardiomyopathy knows where they are going to end up.”

In 2013, after various setbacks, he began suffering atrial fibrillation, an irregular heart rate that causes poor blood flow. Doctors equipped him with a left ventricular assist device to keep him alive and serve as a bridge to heart transplant.

“At that time, he was critically ill,” said Michael Dickinson, MD, medical director at the Spectrum Health Richard DeVos Heart and Lung Transplant Program and Nelis’ longtime cardiologist. “He was going to die without it, probably within a month or two. He was dependent on IV medicines to keep him alive.”

The LVAD, however, prohibited Nelis from submerging his body in water.

That made for some difficult days.

“He’s always been a swimmer,” said Jean Nelis, his wife of 36 years. “When he had the LVAD and he couldn’t get wet … he felt so bad. He always wanted to get back in the pool. And a transplant was the way to do that.”

On June 18, 2014, Nelis, then 59, received the gift of life from an anonymous donor.

To this day, his youngest daughter, Jami Nelis, 28, remembers the carton of water her father kept with him at the hospital.

“That was the goal from the start—to always be able to come back and swim,” Jami said. “He liked the smell of it, to be able to focus on something. It could be months or years from now. But that was the goal, to always be back in the pool.”

As a former high school and college All-American swimmer, and a competitor in U.S. Masters swimming competitions, Nelis wasted no time jumping back into the water.

In summer 2016, after conditioning, he competed in the Transplant Games of America in Cleveland, emerging with gold medals in each of his competitions.

No sooner had his hair dried than he set his sight on the World Transplant Games in Spain.

Water, water, water

The World Transplant Games opening ceremonies began late, with the teams entering the Plaza de Toros one by one, alphabetically by country.

Nelis entered as the last member of the U.S. team. He took his time, his hat off as he waved to his loved ones and snapped photos of the crowd and his teammates.

He savored the moment.

After each team entered the stadium, a thunderous applause rose up when the parade of donor families emerged—an emotional outpouring of gratitude for the gift of life their loves ones had bestowed on the athletes.

Later that night, Nelis and his group enjoyed dinner at an outdoor restaurant in a plaza fronting an old Roman amphitheater.

Nelis seemed low-key as he discussed the opening ceremony and the looming competition. Within 48 hours he’d be competing in the 50-meter backstroke, the 50-meter butterfly and the 50-, 100- and 200-meter freestyle events.

But he’d been fighting a cold and felt jet-lagged. Dehydrated. And keenly aware his blood pressure seemed low.

As he stood to leave the restaurant, he staggered and knocked over a table.

He collapsed into Jean’s arms.

Several bystanders helped lift him, unconscious, onto an empty table. The restaurant’s owner fanned his face with an abanico, a traditional Spanish fan borrowed from a female patron. A waiter held Nelis’ legs above his head while someone called an ambulance.

Paramedics arrived and, after checking his vital signs, advised him to get plenty of rest and drink lots of water.

The long, dry days under the hot sun of Spain’s Costa del Sol were a far cry from the hottest days in Holland, Michigan, Nelis’ hometown.

The first games would begin the following morning, a Monday, but Nelis would still have until Wednesday to recuperate for the start of swim competition.

And although Jean had learned not to underestimate the determination of her husband, she grew concerned as she watched him slump, exhausted, into the taxi that took them back to their hotel.

“It was an emotional roller coaster,” Jean later recalled. “It’s a fragile balance for a transplant patient and you can tip the cart easily. You kind of forget that sometimes.”

On your mark

Even in the best environments, a swim competition can be hot, crowded and noisy.

In the enclosed space of the Centro Acuatico de Malaga on Wednesday morning, boisterous chanting made for a clamorous crowd. Fans of the Argentine and Brazilian swimmers were especially exuberant, lending to an atmosphere more akin to soccer’s World Cup.

Nelis’ family, no strangers to natatoriums, took it all in delight.

“Both parents have always been there for us and have always been our biggest cheerleaders,” Jami said as she waited for the competition to start. “So it’s great to be able to do that now for him.”

For his part, Nelis felt much better.

He knew he’d be diving into a sea of fierce competitors, each bearing the scars of transplant. Many had the names of donors and surgery dates written proudly in marker across their backs and torsos.

Mingled with that competitive vibe was an unmistakable sense of gratitude and respect.

“Everybody here has been through hell in their lives,” Jean said. “And they are happy to be healthy. A new kind of healthy. And happy to be here.”

“The amount of love in this group is humbling,” said Lindsey Rocafort, 29, another daughter. “Everyone has their common person to support, but it is also the camaraderie of the situation that heightens everything.”

Jean, meanwhile, worried secretly about her husband’s health, despite the brave front she maintained for her family.

“I keep telling him, ‘You need to drink, you need to eat, you need to adjust your medications,’” she said.

Nelis’ first day of competition came with surprises—some pleasant, some unpleasant.

In the 200-meter freestyle he took fourth place, finishing 30 seconds behind gold medalist Chikara Wakamatsu, of Japan.

Nelis would come to recognize that name well over the next two days.

In the 50-meter backstroke, not typically one of his better races, Nelis surprised himself and his family with a strong second-place finish, gliding in half a second behind Great Britain’s Simon Randerson.

Nelis dedicated that medal to his anonymous heart donor.

“There isn’t a lot more you can say to the donor family,” Nelis said. “Three years of effort has gone into this. My note is just going to say, ‘Thank you.’ There are just no words to express your gratitude to a family that parted with their loved one.”

His family’s sentiments were evident.

“I’m pretty proud,” said another daughter, Kelly Nicholas, 33. “It was a little emotional, but fun to see. Dad’s been to about a thousand of my swim meets—and it’s nice to be able to go to one of his.”

Spirit of competition

As Wednesday progressed, Nelis also won a silver in the 50-meter butterfly. Once again, he finished just behind Wakamatsu, who set a blistering pace.

The day’s final race, the 100-meter freestyle, was historically one of his stronger competitions.

He got off to a good start, keeping pace much of the first lap.

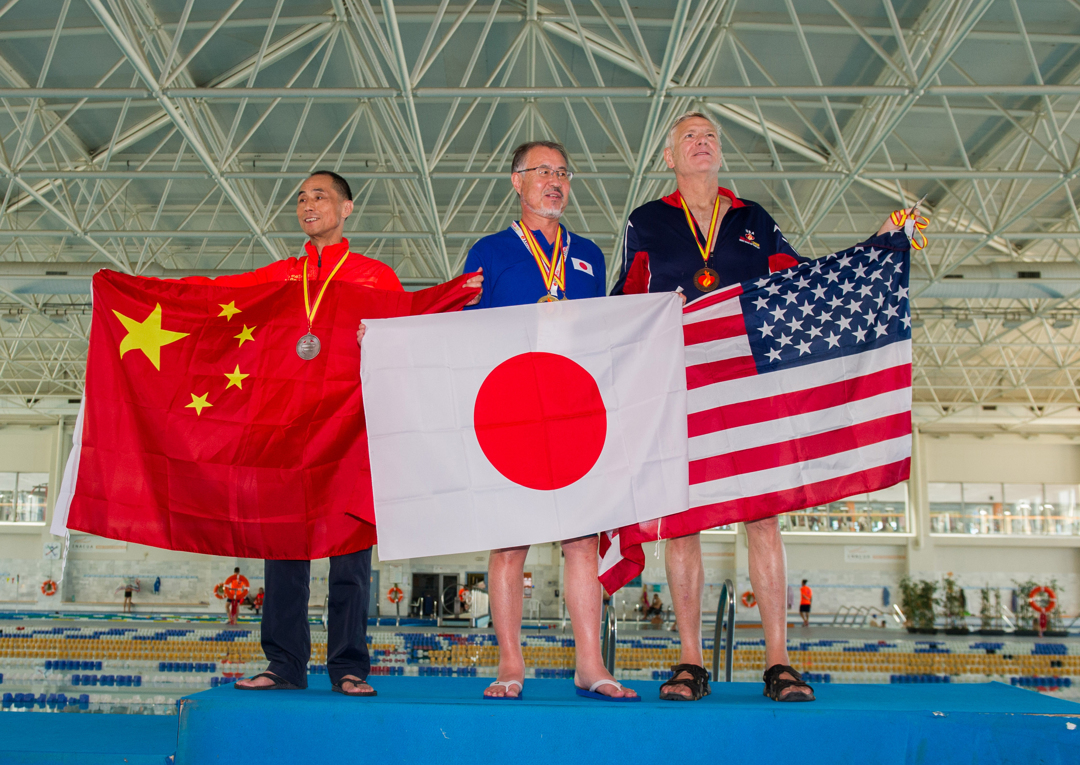

After the turn, however, two swimmers began to pull away. A late kick put Nelis next to the swimmer in the lane to his left, Lu Jin Xiang, of China. Both men appeared to slap the wall simultaneously, but the official time showed Xiang edging Nelis by 0.33 seconds for the silver medal. He finished seven seconds off the gold medal pace set by Wakamatsu.

Nelis took home the bronze.

On Thursday, Nelis would get one more chance at Wakamatsu, in a showdown in the 50-meter freestyle.

Nelis’ final event demanded a no-holds-barred race from one end of the pool to the other.

No holding back. No saving energy for a final kick. No hopeful spurt to overcome the leader.

As the bell sounded, both swimmers got off to a strong start.

Nelis’ strong, fluid strokes propelled him along lane 5. Wakamatsu kept pace in lane 4.

At the halfway point, it appeared the two were neck and neck. Both swam several body lengths ahead of the nearest competitor.

As Nelis and Wakamatsu cruised toward the finish, it looked, from Jean’s angle, like a dead heat.

Both swimmers appeared to touch the wall simultaneously.

As the two men leaned over the ropes to shake hands, the official time showed Wakamatsu won by a mere 0.65 seconds.

The gold would elude Nelis this year.

After his final race, he found the awaiting arms of his family.

“I’m ecstatic,” Jean said. “I’m much more relaxed. He’s done great. I didn’t realize I was nervous, but now that it is over, I’m relieved.”

Nelis felt relieved, but perhaps a little motivated, too.

The 2019 World Transplant Games are slated for Newcastle, England.

“We’ll have to see,” Nelis said, mulling the idea. “I tried very hard, but there are a lot of talented swimmers here.”

At the very least, he expects to be ready for next year’s Transplant Games of America in Salt Lake City.

“Although I have always wanted to see Ireland, my mother’s homeland,” he added with a mischievous grin.

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

As a 53 year old liver transplant recipient, this story exemplifies how much the donors give to us, and we owe it to them to make the very best of our gift.

Wonderful sentiment, Chuck! Thank you for sharing! 🙂

What a great story. The gift of life-God has given you another chance.