Ryan Brown, 22, lay writhing in pain and gasping for breath on the pavement of Lafayette Street in downtown Grand Rapids, Michigan.

Only moments before, he’d been riding his moped to his nursing class at Grand Valley State University when a silver Impala struck him.

He moved his head from side to side, then wiggled his fingers and toes—just to be sure he still could.

“I thought, ‘OK, I’m not paralyzed,’” Brown said.

When he had flown off the moped, he had slammed up against the front wheel of the car. The left side of his chest had absorbed the brunt of the impact.

“I felt excruciating pain to my left chest wall and I felt as if my lung was a balloon with a hole in it as I took very short, whimpering breaths,” Brown said.

When emergency crews arrived, he could scarcely talk.

“I was only able to communicate one- or two-word responses to bystanders and the EMTs as I squirmed and whimpered on the ground,” he said. “The ambulance got there within five to 10 minutes, but it felt like an eternity.”

A ‘devastating’ injury

The ambulance rushed him half a mile away to the emergency department at Spectrum Health Butterworth Hospital, where Gaby Iskander, MD, division chief of the hospital’s acute care surgery department, stood ready.

Dr. Iskander found Brown had suffered a “devastating” chest injury.

“I have been doing trauma for 25 years and I have never seen a chest injury as bad as this one,” Dr. Iskander said. “It destroyed the whole left side of his chest.”

Brown’s ribs had been driven inside his body, completely tearing through the muscle of his diaphragm. Part of his abdomen had moved inside his chest. He also had lacerations to his spleen and left lung and he suffered massive internal bleeding.

Normally, Dr. Iskander said, a patient in this condition would be rushed into emergency surgery. But Brown’s injuries were so severe that surgery might have hurt more than helped.

Instead, doctors focused on saving Brown’s life by stabilizing him, supporting his breathing and circulation.

And that approach worked.

A tricky fix

Brown soon stabilized in the surgical intensive care unit.

Spectrum Health acute care surgeon Alistair Chapman, MD, would be tasked with putting Brown’s ribs back together. He immediately began plotting out the surgery.

Dr. Chapman specializes in rib plating surgery, but even he knew the extent of the challenge.

He prepared Brown for the road ahead, including possible complications.

“We see a lot of rib fractures, but this is probably one of the worst—if not the worst—that I have seen,” Dr. Chapman said. “This particular injury is simply jaw-dropping.”

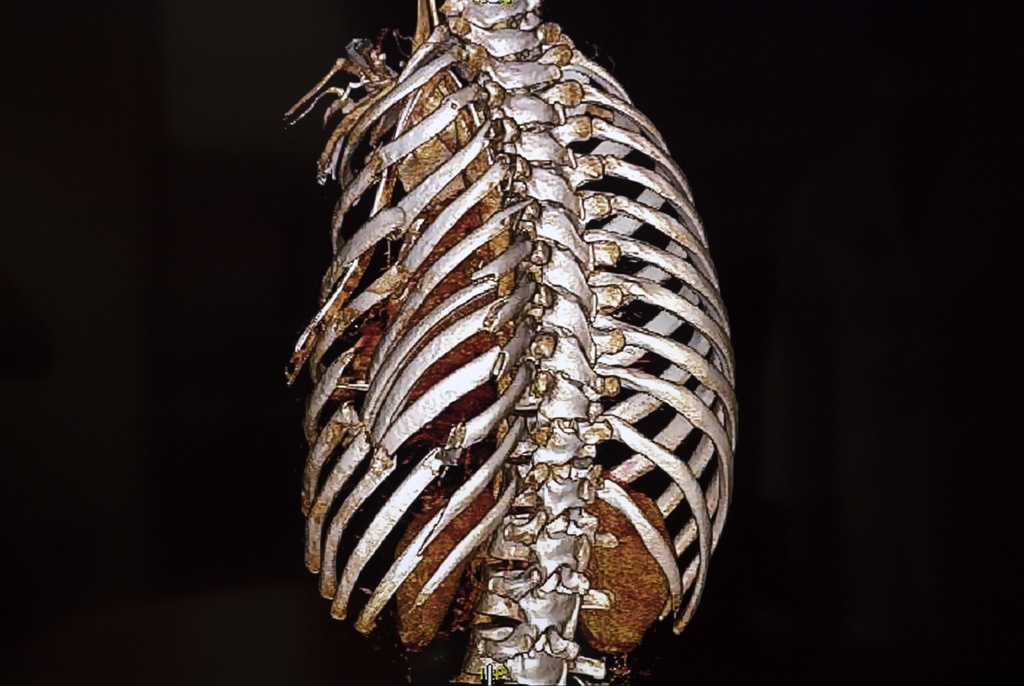

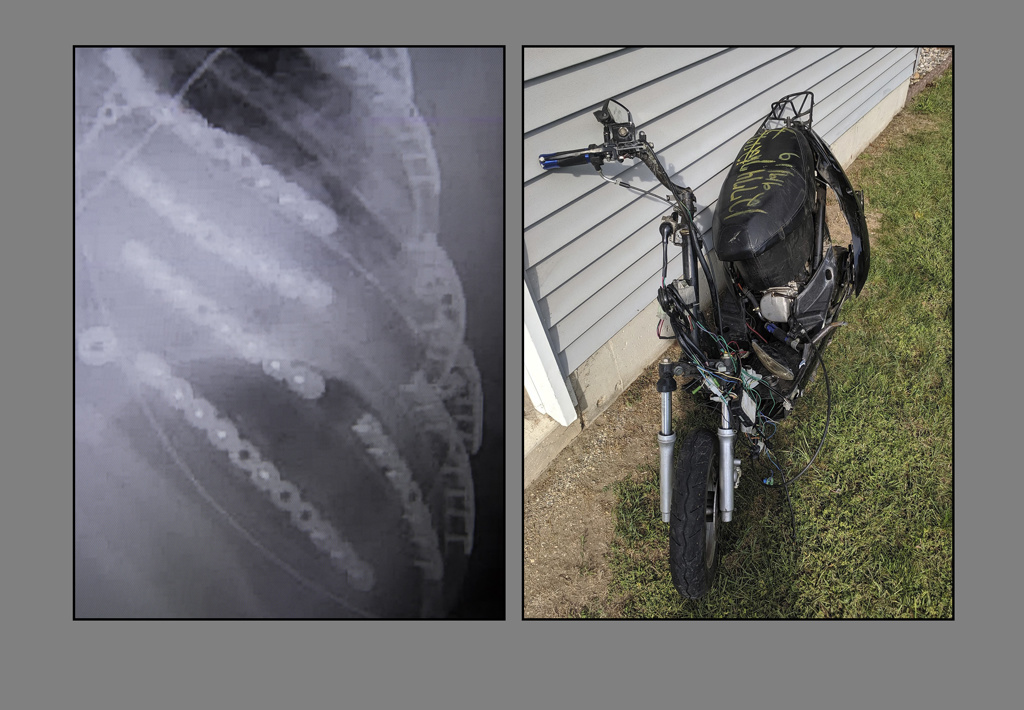

There are 12 ribs on each side of the body. On nine of the ribs on his left side, Brown suffered 19 different breaks.

Three consecutive ribs—ribs seven, eight and nine—were broken in two or more places. This meant Brown had a very serious condition called flail chest, essentially a floating segment of ribs.

The left side of his chest had sunken to about 25% the size of his right.

“Every chest wall injury pattern is quite different,” Dr. Chapman said. “And his was very complex.”

Dr. Chapman would need to reconstruct Brown’s chest wall. He would do it with a muscle-sparing technique—a minimally invasive approach that makes the surgery more difficult to perform, but also makes healing and long-term results much better for the patient.

Surgery came Sept. 14, 2019, just five days after the crash.

Nine hours, 11 titanium plates and 66 screws later, Dr. Chapman had pieced Brown’s ribs back together.

Headed home

On Sept. 20, 2019, doctors discharged Brown to Mary Free Bed Rehabilitation Hospital. Five days later he returned to his parents’ house, where he would complete the long road to recovery.

At the time of the crash he’d been working toward his registered nursing degree at college. During his recovery he took a semester off to heal.

A year later, he’s back at it—and plans to graduate in December.

He’s also back to his job as a nurse technician at Spectrum Health.

He hopes his experience will make him a better nurse.

“I feel like I had personal-empathy hours,” he said. “Just being on the other side of things, I noticed when the nurses or doctors would just do the smallest gesture, it meant the world to you. Some of those little things, I want to put that into my practice because that meant so much to me.”

He has his sights set on a job in the same intensive care unit where doctors treated him.

“I just feel like I have this debt that I want to repay to every patient I have,” Brown said. “If I picture myself in that hospital bed, I can take better care of them.”

That’s an invaluable advantage, Dr. Chapman said.

“Most of us don’t have that,” Dr. Chapman said. “I think he’s going to have a unique perspective of understanding being a critically ill, traumatically injured patient. Throughout his career he’s going to be able to provide an inspiration to his patients because they will see him right in front of them, doing so well.”

Brown is getting used to what he calls his “new normal.”

His left side still feels stiff. He experiences pain in his back, particularly if he has been on his feet for a 12-hour shift.

But he sleeps fine now. He’s able to do what he loves, including church league softball and snowboarding.

“You never know if it could be your last day,” Brown said. “I’m thanking God every day for another day.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

August 30th 2019 I suffered a very similar accident where a car hit me at 62 miles an hour while I was on my motorcycle going 55 to 60 miles an hour I had 15 broken or cracked ribs and Dr Iskander was my chief surgeon they did a wonderful job it’s been a year later and I’m back to almost normal

Wow what a wonderful story about this young man and the skill of staff at Spectrum Hospital. Best of luck to you Ryan Brown with your studies and making a difference! You are an inspiration!

Ryan,

Your story of resilience is inspiring to so many. Thank you for sharing it.