The coffee slipped from his right hand, but it didn’t hit the floor.

Neither did he, thanks to his fast-acting friend.

It all happened in an instant: Robert Bennitt slipped into darkness and slumped down into his seat inside Red Rock Grille in Kent City, Michigan. His friend, Steve Johnson, reached across the big round breakfast table to pull him up.

The two men and some others had met up for a bite to eat that morning last fall, but shortly into it Bennitt fell unconscious at the table.

Later, of course, he’d learn how a clot broke free inside him and made its way from his neck into his brain. It rendered him unconscious in a split second, and he avoided a nasty fall to the floor only thanks to Johnson’s quick hand.

Former ambulance medic Al Follette was in the restaurant that morning, too. He remembers rushing to Bennitt and touching his throat to feel for a pulse.

“It was very irregular,” Follette said. “I yelled to call 911.”

To Follette’s amazement, Bennitt regained consciousness and began to speak as if nothing had happened.

Bennitt, of Casnovia, Michigan, assured everyone he didn’t need a trip to the hospital, although when his wife arrived just ahead of the ambulance, there was no debating it—he would go to the hospital.

Curiously, Follette still remembers the sign hanging on the wall near the table that morning: “There will be a $5 charge for whining.”

No worries. Bennitt, 76, had never been one to whine.

Critical timing

A stroke occurs when blood flow is cut off from an area of the brain. The oxygen-deprived brain cells begin to die, and when that happens, certain abilities controlled by that area of the brain—memory and muscle control, for instance—are gone forever.

The National Stroke Association characterizes a stroke as a “brain attack.” About 800,000 people experience it each year, and it’s the fifth-leading cause of death in the U.S.

The signs are unmistakable: A person experiencing stroke may have weakness or numbness in an arm or leg, and one side of their face may droop. Their speech may also become slurred and they’ll find it difficult to repeat a simple sentence.

A stroke victim can also have trouble walking, and they’ll stumble or experience sudden dizziness. They may also have difficulty swallowing and they will experience headaches, mental confusion, or rapid involuntary eye movement.

A patient’s symptoms will depend on two things: Where the stroke occurs in the brain, and the extent of the damage.

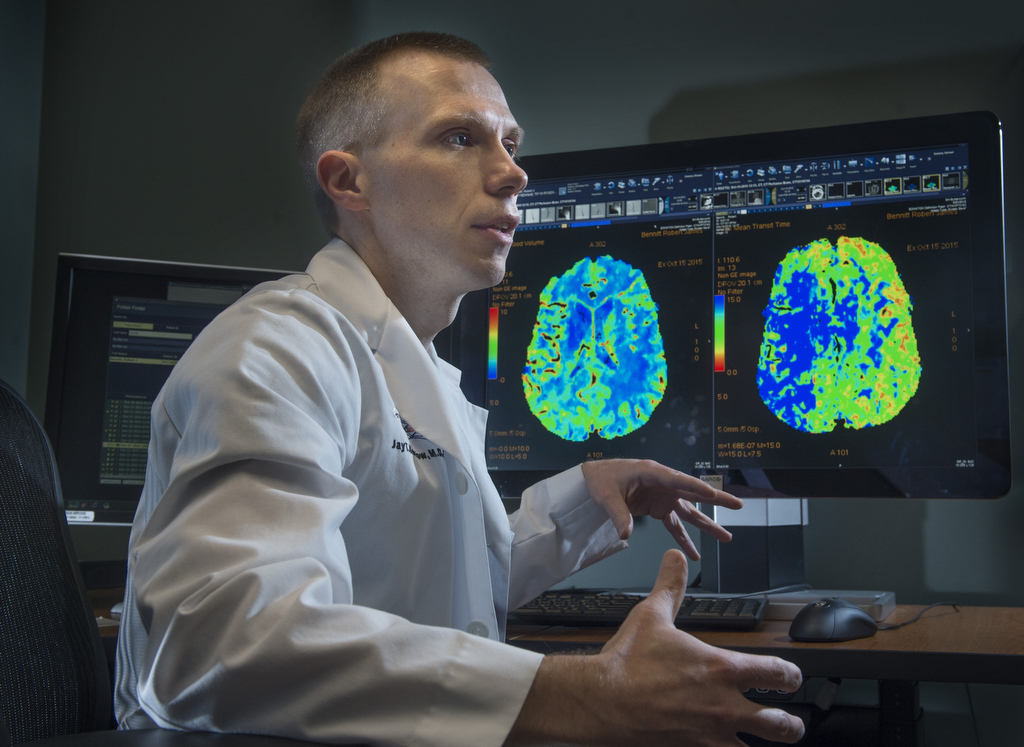

In Bennitt’s case, a segment of internal carotid artery in his neck was almost completely closed up, said Jay Morrow, MD, a neurointerventional and interventional radiologist at Spectrum Health. On the right side of Bennitt’s head, a segment of internal carotid artery was entirely occluded, as was the middle cerebral artery.

When the clot broke off and tumbled into his brain and blocked an artery, Bennitt was in deadly danger from ischemic stroke.

Millions of his brain cells could die each minute. And once gone, there was no getting them back.

In such moments, speed is critical.

Bennitt was fortunate. The breakfast crowd at the Red Rock Grille knew what was happening and they got an ambulance there quickly.

And when he arrived at Spectrum Health Butterworth Hospital, doctors were quick to use a relatively new stroke treatment involving a device called Solitaire.

The procedure doesn’t just dissolve a brain-killing clot—it removes it altogether.

The FDA approved it in 2012, and Dr. Morrow used it at Spectrum Health later that same year. He was, in fact, the first physician to use the procedure in West Michigan.

“I’ve been using Solitaire for four years at Spectrum Health with good results,” Dr. Morrow said. “It has been just a little over a year that landmark studies were published in prominent medical journals, which prove the effectiveness of endovascular ischemic stroke treatment.”

Previously, and in many cases still, drugs alone are used to dissolve a clot. This new procedure, using a device known as a stent retriever, physically removes the clot.

It’s done mechanically, with the doctor first inserting a guide wire and then a catheter into the patient’s artery, then inserting a device that feeds up and out of the catheter, where it then essentially enmeshes the clot and extracts it.

Throughout the procedure, the doctor and his team use fluoroscopic imaging to see inside the artery.

Bennitt is one of two patients who Dr. Morrow treated this past fall for ischemic stroke.

“These patients would have had large strokes that would carry greater than 50 percent mortality if left untreated,” Dr. Morrow said. “They are also the type of strokes for which intravenous (drugs) are largely ineffective.

“Today, both individuals are completely independent,” the doctor said. “It would be difficult to tell that the individuals even had a stroke.”

Symptom free

During a recent checkup at Spectrum Health, Bennitt wondered aloud at the “what ifs.”

He fought back tears and his breath grew ragged as he listened to a doctor tell him how close he came to disaster. Next to him sat his wife, Barbara, who reached out for his hand. His emotions are not all for himself.

Before the stroke, Bennitt drove a heavy truck for Nyblad Orchards in Kent City, Michigan. The morning of his stroke, he had planned to head to work after breakfast.

Plans change. He didn’t go to work. He no longer drives truck.

“What if this had happened while I was driving?” he wondered aloud.

There’s always plenty to think about afterward. Like this: What if he hadn’t received rapid treatment with a new procedure?

Some people recover from strokes, but more than two-thirds of survivors are left battling some type of disability.

To this day, Bennitt is symptom free. It’s likely due in large part to the quick use of the new procedure.

Spectrum Health’s approach to stroke treatment—stent retrieval, combined with medicine—has led to much better outcomes for patients, said Muhib Khan, MD, a vascular neurologist at Spectrum Health.

Clot removal is part of the new frontier in stroke treatment.

“We’ve had success treating strokes, previously with drugs and now with stent removal,” Dr. Khan said.

While the medical world can’t restore brain cells that have died—once they’re dead, they’re dead, Dr. Khan said—that doesn’t mean researchers aren’t trying.

That could be the next frontier for treatment.

“In the future, we would restore the cells and limit permanent damage,” Dr. Khan said.

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>