Alzheimer’s disease is a bewildering diagnosis for any family to confront.

Ginger Sisson and her son, Christoph Sisson, want to help bring it out of the shadows.

With guidance from Christoph, 57, who’s also her full-time caregiver, Ginger, 80, is sharing her experience in a monthly podcast called Living With Alzheimer’s.

The mother-and-son duo hope to help patients with Alzheimer’s—and their family members—talk more openly about the disease. About 6.2 million Americans live with Alzheimer’s, an illness that people sometimes find difficult to discuss, particularly when they see it affect their own family members.

Ginger is a former English teacher and retired librarian.

“I just totally enjoy words, period,” she said.

The two make a great team.

Christoph is a former journalism teacher and amateur radio host.

Together, they’ve found their podcast helps them process the changes Ginger is going through. And, at the same time, they hope it’s helping other families adjust.

Their informal, honest conversations are balanced with experts on other subjects, with topics ranging from yoga to documenting memories to social engagement.

For both mother and son, the endeavor has helped ease their fears of the unknown.

A deeper understanding

Spectrum Health doctors diagnosed Ginger with Alzheimer’s in 2019.

“I didn’t really have a great understanding of what that would mean,” Ginger said. “It took me a while to figure out that there were increasing moments when I had to go to somebody else to clarify what I was doing or where I was going.”

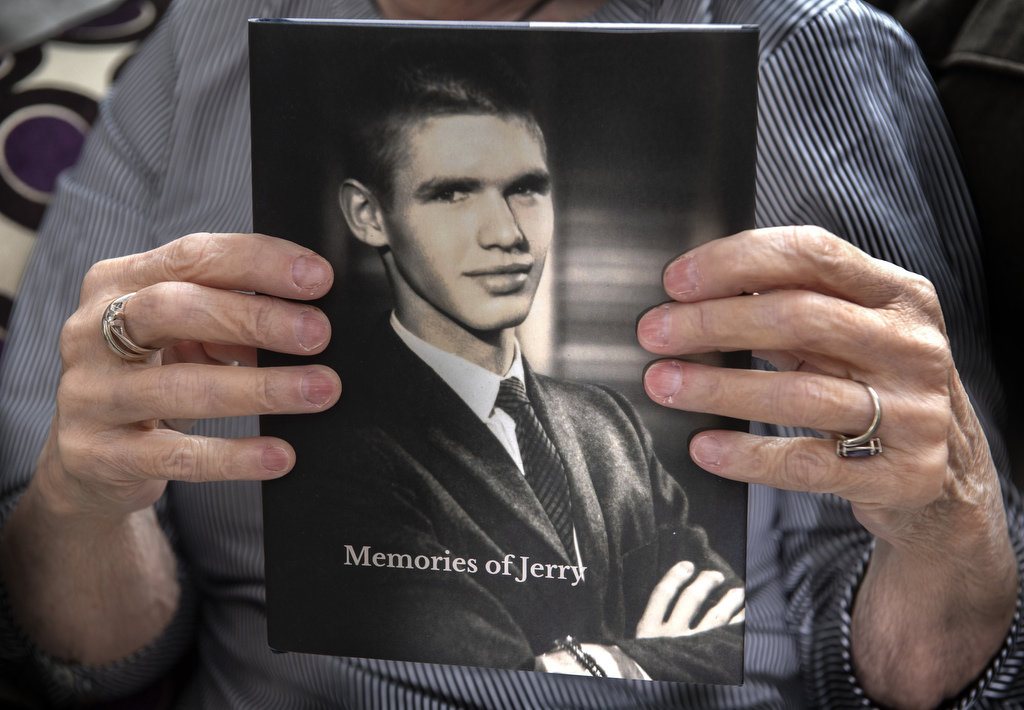

Jerry, her husband, had been diagnosed with vascular dementia.

Christoph and his family arranged for Ginger and Jerry to move into an assisted living facility in January 2020. Within months, COVID-19 drastically altered their visitation schedules, a difficult situation for everyone.

Jerry then grew ill with cancer. He died in fall 2020.

Loneliness quickly became a factor, Christoph said.

“It was clear that even after a few weeks, Ginger felt very isolated,” he said.

After lots of soul-searching, family conversations and work with a counselor, Christoph decided to become his mom’s full-time caregiver.

He left his life in Kansas City and he and his family took Ginger out of the assisted living facility.

“It just became apparent that it was really important to me,” Christoph said. “After a lot of consideration, I realized that this is something that could be very rewarding for both of us. And thankfully, that’s proved to be true.”

When they launched the podcast, it helped Christoph dig deeper into issues that patients like his mom face.

“I wanted to know more about dementia and the best practices for caregivers,” he said.

He grew frustrated with the way so much information and experience remains hidden away, even by people he knows.

“It seemed like everyone I spoke to would say something like, ‘Oh, my mom had Alzheimer’s, and I cared for her,'” Christoph said. “But I had known these people a long time and never known that. It became very clear that Alzheimer’s is not part of our day-to-day conversations.”

Another motive for the podcast?

“I was considering how I might keep her as engaged as possible,” Christoph said of his mother. “And knowing that she loves conversation, it seemed a good idea to involve her in some storytelling of her own.”

‘Many windows’

The Sissons record their podcast at home, in a little recording studio Christoph pulled together.

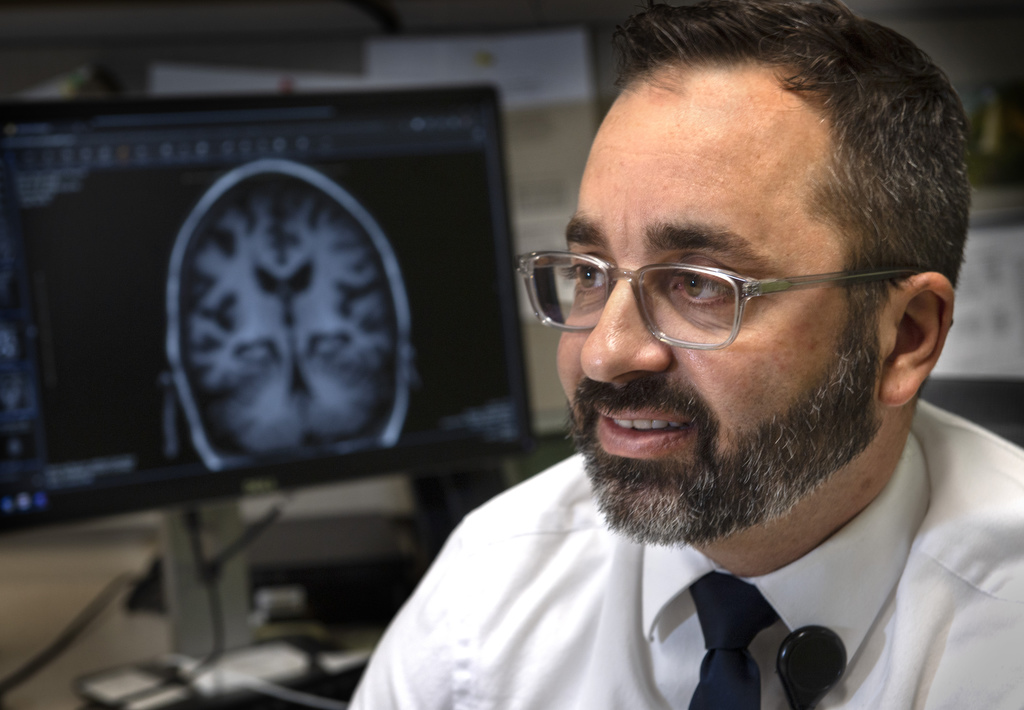

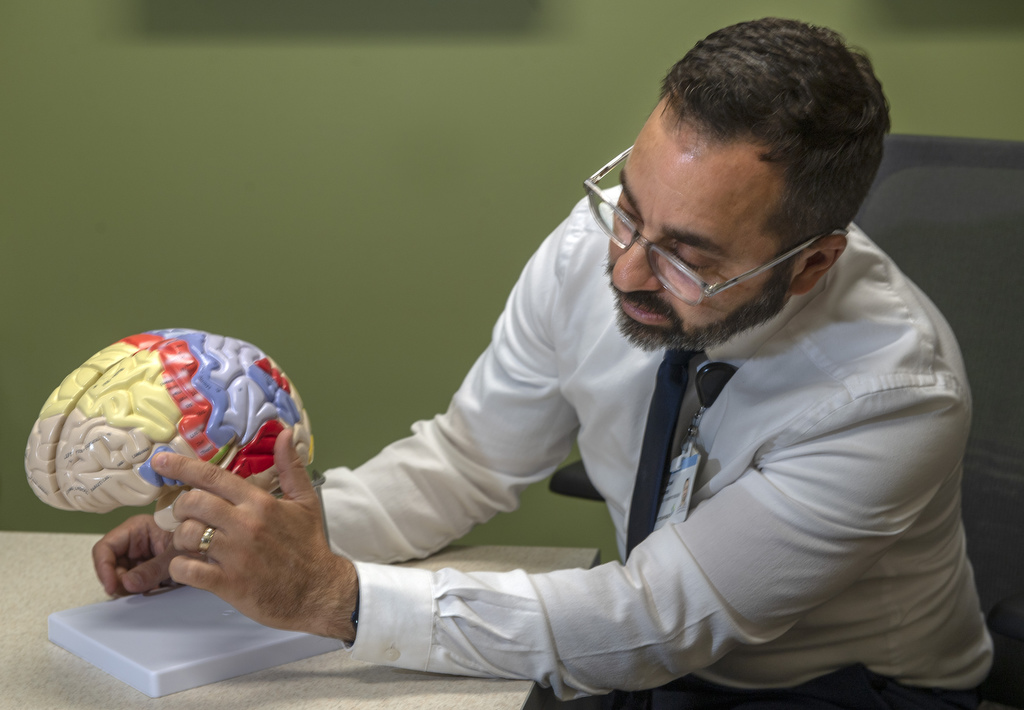

It has been a great way for them to make sense of a difficult diagnosis, said Michael Lawrence, PhD, the Spectrum Health clinical neuropsychologist who treats Ginger.

“Switching roles from child to caregiver is difficult,” Dr. Lawrence said. “And the podcast is a way for Christoph to educate the public and pull the curtain back on what it’s like.

“And it also allows Ginger some dignity, to talk about her health and her mind. That probably helps her process and cope with what she’s losing.”

The podcast is one more tool to help dispel perceptions about Alzheimer’s as an either-or condition.

“There are many windows as the disease progresses,” Dr. Lawrence said. “And there are often some very good moments, even on bad days.”

Respectful caregiving involves meeting people with dementia precisely where they are at a given moment.

If someone with Alzheimer’s is having a difficult moment, for example, it sometimes helps to give them an hour or so. It’s unrealistic to expect them to reason things out if they’re having difficulty.

“Alzheimer’s is a marathon,” Dr. Lawrence said. “Not a sprint.”

Caregiving can put family members at a higher risk of burnout, depression or chronic health problems.

Christoph has been careful to protect himself, turning to paid caregivers and other family members to offer him breaks.

“I make sure that there’s time for me to see friends, to get some respite,” he said.

He has a bowling night, for example, and makes time to get away for short weekend trips when he can. He also relies on a counselor, a valuable resource for discussing the complex challenges of caring for someone who is increasingly struggling.

“It’s just another way for me to take care of myself,” he said.

The Alzheimer’s Association runs virtual support groups, which are free and confidential. This type of emotional, behavioral and educational support is invaluable as families come to terms with the sometimes baffling illness.

Plenty of happiness

It can be difficult to describe the progression of Alzheimer’s disease, because each person’s experience will vary. But on average, a person lives four to eight years after diagnosis—although some people can live as long as 20 years, depending on other factors.

And there’s no predictable timeframe for the phases of the disease.

“Typically, short-term memory tends to go quickest, followed by language declines,” Dr. Lawrence said. “And the windows when patients can engage get shorter and less frequent.”

That’s true for the Sissons.

Christoph is keenly aware of his mother’s progression, but he has found that she’s typically at her best at about 2 p.m. each day. When they started their podcast, Ginger could interact more readily with guest speakers.

“But that’s become more and more difficult,” Christoph said.

He now interviews the experts separately, then edits those parts in with Ginger’s responses.

“At some point, I’m assuming her ability to interact will be diminished, so she can’t participate much,” Christoph said.

He hopes to keep the podcast going as long as his mom can be involved.

Maybe even beyond.

“There’s a lot of evolving information about the disease and about how to care for the many people who have it,” Christoph said.

Those changes can be heartbreaking.

“You lose a little piece of your family every day in this slow, gradual slipping away,” Dr. Lawrence said.

But because the Sissons have been proactive about Ginger’s care, they’re both better prepared.

That’s the benefit of early diagnosis, Dr. Lawrence said.

“We can help people figure out medications and understand what life might look like two years from now, or five,” he said. “We talk about hoping for the best, yet help plan for the worst. That way, families don’t get caught in a crisis.”

For Christoph and Ginger, that long view has tempered sadness with plenty of good days—and plenty of happy moments.

“I still like to watch TV,” Ginger said. “And sit with the cats in my lap. And in the summer, I love to sit on the deck watching what’s happening in the neighborhood. And I still enjoy my roses.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

Thank you for sharing your journey Christoph & Ginger. And helping others.

Thank you for sharing this story. I loved it. I give Christopher credit for the way he is going about caring for his mom, in such a loving way. My mother also had Alzheimers so I could relate to this story. God bless you both!

Are there any tests that can be given to diagnose Alzheimer’s? I have a brother that has been diagnosed w/Alzheimer’s at 80. My older sister died at 84 but, did not have Alzheimer’s . Is this disease hereditary? I am 79.

Hi Pat, Thank you for reading and for the question. According to the Alzheimer’s Association, there is no single test that can determine if a patient has Alzheimer’s disease. Doctors consider a number of factors in reaching a diagnosis, including physical examination, symptoms, medical history, cognitive tests and brain imaging. The Alzheimer’s Association website offers additional information that may be helpful in respect to diagnosis and genetic aspects of the disease.

Thank you!

Thank you for doing this! I will share it with my mom and dad as they are on their own dementia journey

christoph – I remember talking with Ginger about you lots when you were young. I’m so sad to learn of her struggle but so glad for the two of you to be sharing this part of her journey. So beautiful. So hard. I hope you both find much joy along the way.

What a gift you are giving here, Ginger and Christoph. Sharing your own experiences can truly help others on this challenging journey.