In October, a bullet shattered Paolo Bautista’s arm in a mass shooting at a country music concert in Las Vegas.

As the bullets rained down on concertgoers, Bautista’s quick-thinking sister stuffed her wound with a sock. A stranger pulled a belt tight above the hole. Doctors say this makeshift tourniquet saved Bautista’s life.

Fifty-eight people died in that incident.

As the number of mass shootings in America increases—there were 11 school shootings in the first three weeks of this year—advocates would like to see tourniquet kits made available in public spaces such as schools, shopping malls and arenas.

Doctors believe tourniquets could potentially save lives if they were more readily available in places where mass shootings can occur.

“In reality, bystanders are usually the first responders,” said Laura Maclam, injury prevention and outreach coordinator for trauma services at Spectrum Health Butterworth Hospital. “Whether it’s three minutes or six minutes or nine minutes that you’re waiting for the ambulance, if you can get care during that time, it can be the difference between life and death.”

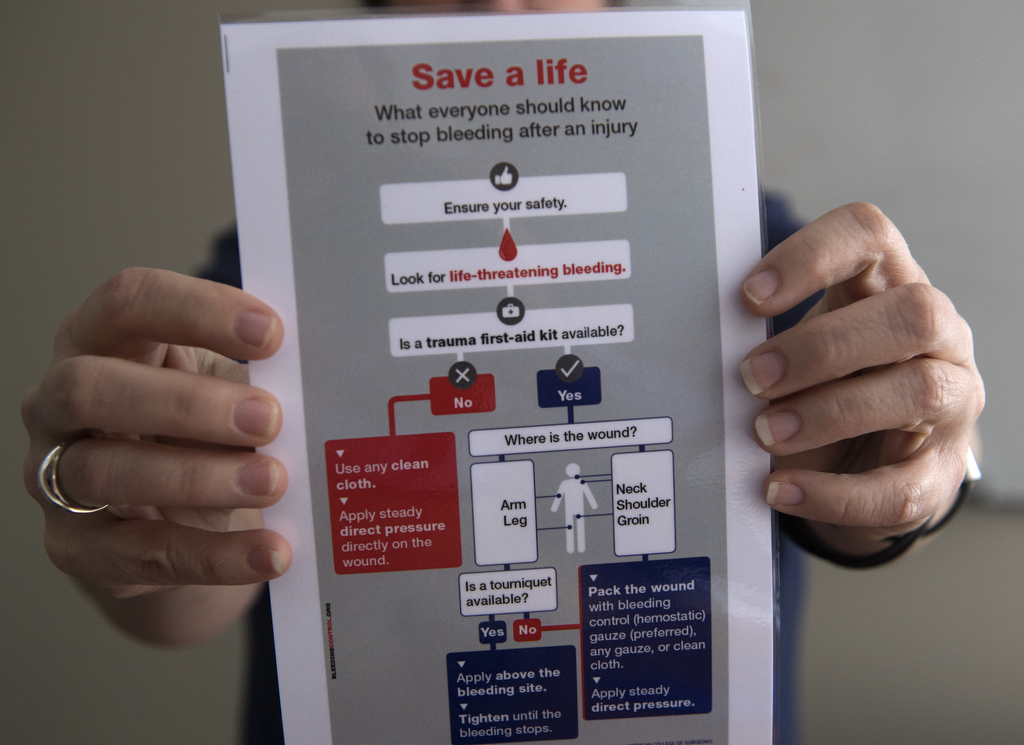

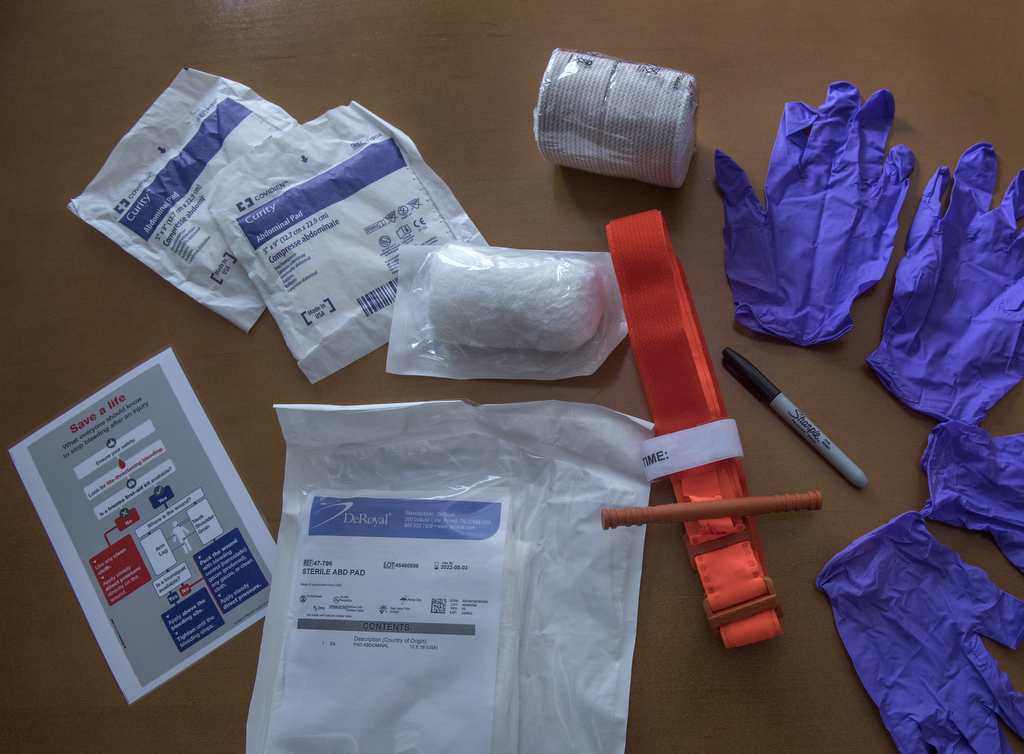

Maclam is spearheading Butterworth Hospital’s Stop the Bleed campaign, part of a nationwide effort to increase the number of tourniquets in public spaces and teach citizens how to apply them.

“Just like we train people to administer CPR, we should be training people on how to stop bleeding,” Maclam said.

Past is present

Tourniquets are not a new invention.

As Alexander the Great marched through Asia and northeast Africa during the fourth century B.C., tourniquets were used to staunch the bleeding of wounded soldiers.

They were used by the ancient Romans under Julius Caesar and during the American Revolution under George Washington, and by nearly every army in between.

The most basic tourniquet is basically a tight cord or bandage placed above a wound, which compresses the limb and restricts blood flow. It prevents injured people from quickly bleeding to death.

But tourniquets fell out of favor after World War II, when medical experts blamed prolonged cutoff of blood flow for the number of amputations soldiers were suffering.

Transportation was much worse in those days, and it often took many hours—if not days—for wounded people to get treatment. That’s no longer the case.

The thinking began to change after a study found that 10 percent of combat deaths in the Vietnam War could have been prevented by tourniquets.

In the 1980s, the Israeli military adopted them. And by 2005, the American military had re-adopted them after a study at an Iraq hospital showed that 87 percent of patients who came in with a tourniquet survived. Among those who were good candidates for tourniquets but didn’t receive them, none survived.

“Tourniquets have come along way,” Maclam said. “When applied properly, they can cause quite a bit of pain, but they stop blood loss very effectively.”

If a tourniquet stays on many hours it could still lead to amputation, but that rarely happens, Maclam said. And even if it did, “loss of limb is better than loss of life.”

Life lessons

The Stop the Bleed campaign began in 2012 after the Sandy Hook school shooting in which 20 children and six adults were massacred.

“There’s a research project called the Hartford Consensus that came together after Sandy Hook,” Maclam said. “What they realized: Potentially several of those lives could have been saved if some bleeding could have been controlled at the scene.”

The Obama administration heavily promoted the Stop the Bleed campaign. It recommended that tourniquet kits be added to locations where automatic external defibrillators are available—places such as stadiums, business offices, airports, airplanes, hospitals and shopping centers.

Maclam and Butterworth Hospital’s goal is to get tourniquet kits in as many places as possible in Michigan.

They’re providing free or low-cost training to any person or group who wants it. The Spectrum Health Foundation recently donated $10,000 to the campaign.

Maclam said anyone, including children as young as 11, should be taught the basics of how to stop bleeding in an emergency scenario.

“I think I could teach anyone,” she said. “It can be a little scary—some people don’t want to think about blood or an open would—but it’s just like teaching someone CPR or an AED. It’s a little upsetting, but it’s important.

In the last decade, 40 percent of mass shootings have occurred at education institutions, Maclam said. These types of large gathering places are prime for this sort of campaign.

“So, looking at universities, local schools, the arena, the places you think about where people gather—sporting events, malls, school buses, elementary schools, mass transit,” she said. “There’s a program out of Seattle—they have light rail there—and they taught all their employees. Any opportunity where people can gather, those are probably the best targets and the best places for installation and training.”

Beginning last year, Michigan passed a law requiring students to learn how to administer CPR and AED before graduating. Maclam believes tourniquet kits should be included in that curriculum.

“I think this will be included with that education moving forward,” she said. “In order to graduate, what a great thing to add.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

Good job

Nice work Laura! What a great program!

How truths change over time! In the 70s and 80s we spent a lot of time trying to convince people taking first aid NOT to use tourniquets, citing the people who died when people foolishly applied tourniquets to the chest area to stop bleeding of the head and neck that should have been stopped with direct pressure, and the tourniquets were so tight they compromised respiratory function and at the ED the victims were found to be profoundly anoxic, etc. Talked to many ED nurses, they all had stories of the damage tourniquets could do if not wisely used. Yet I was taking my Boy Scouts regularly into the back country, where medical help could be either hours or days away- so in my Merit Badge teaching I taught the use of tourniquets and that each injured with tourniquets was to have a big T marked on their forehead using whatever was to hand and teaching the count to 10 release and re-establishment of the tourniquets to try to mini.ize the results of lack of blood , and nerve pressure.

Now that I’m retired and travelling in my RV I’ve thought of adding the clotting factors out there on the first aid aisles for treatment of profuse bleeding, and after reading this article I think I’ll also add tourniquets.

Happy travels to you, Mitzi!