When Denise Veltkamp’s friends from church came to clean her house one day last February, she took it as a wake-up call.

Weak and constantly short of breath after two hospitalizations because of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Veltkamp realized she had a choice. She could either accept dependence on others as her new normal or she could push back against her COPD.

For someone who’d always done everything for herself, losing her independence at age 71 wasn’t an option.

“I just decided I wasn’t going to live that way,” said Veltkamp, who lives outside of Sand Lake, Michigan. “I’m too young to depend on my children and my grandchildren and my church friends to take care of me.”

She decided to fight back.

Taking the advice of her pulmonologist, John Cantor, MD, she enrolled in the pulmonary rehabilitation program at Spectrum Health United Hospital in Greenville, one of five Spectrum Health pulmonary rehab locations. The Greenville-based program recently received certification from the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation.

The first few sessions were rough for Veltkamp. She almost gave up on day one when a respiratory therapist asked her to walk for six minutes to establish her personal baseline.

“I said, ‘You’ve got to be kidding me—I can’t even walk two minutes,’” said Veltkamp, who arrived at the facility in a wheelchair. But taking it at a snail’s pace, she made it.

As the weeks went by, she slowly built up her strength and stamina. Now she can drive to the grocery store and do her own shopping. Though she’ll always need to be on oxygen, pulmonary rehab has made a huge difference in her life.

“Because the stronger you are, the easier it is to breathe,” Veltkamp said.

Monitored exercise

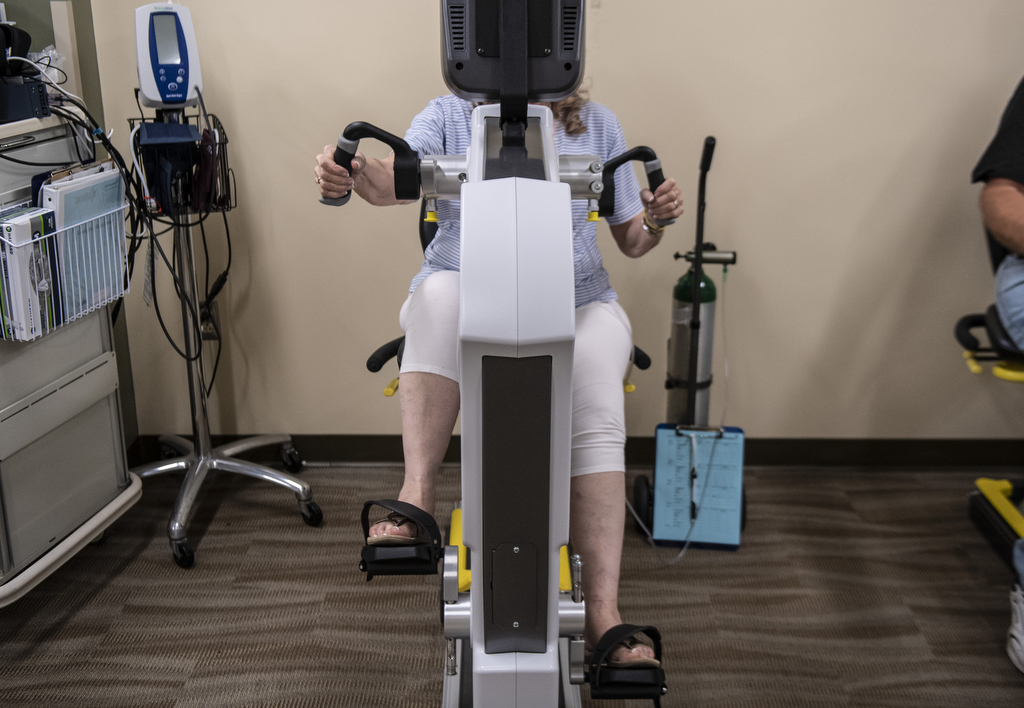

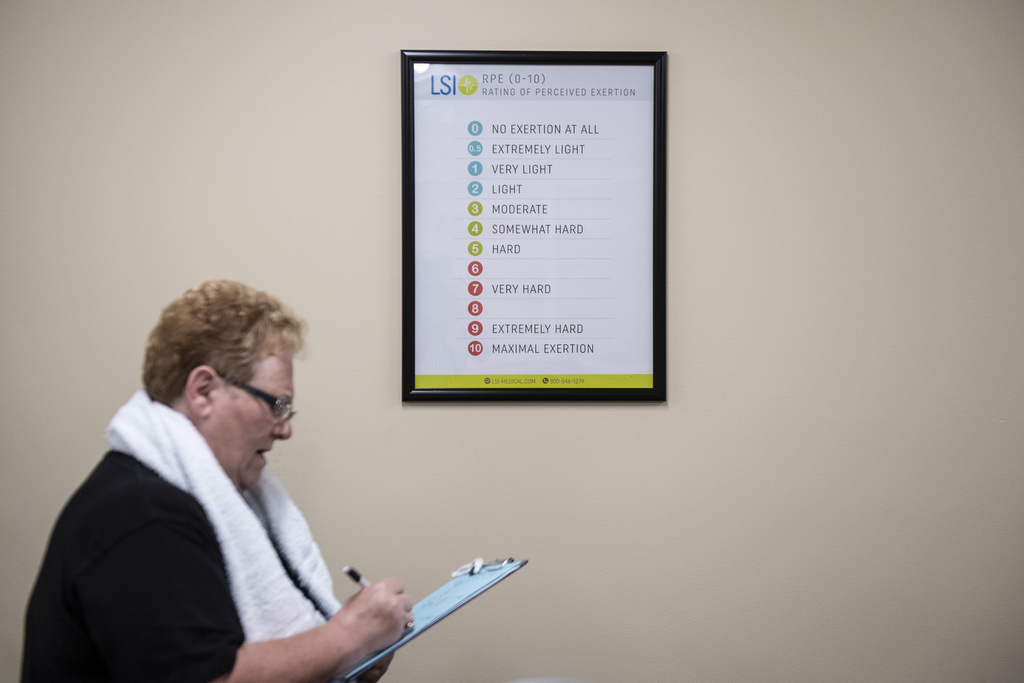

Pulmonary rehab looks like a typical aerobic exercise program, except participants move at a slower pace and stop between activities to have therapists monitor their oxygen saturation and other vital signs, said Dana Adams, a respiratory therapist who leads the cardiac and pulmonary rehab programs at United Hospital.

Two or three times a week, patients use treadmills, exercise bikes, stair steppers and weight machines. Oxygen tanks are available for patients who need them. Once a week, participants stay for an hour of pulmonary education to help them manage their disease. The eight-week program is covered by Medicare and most insurance plans.

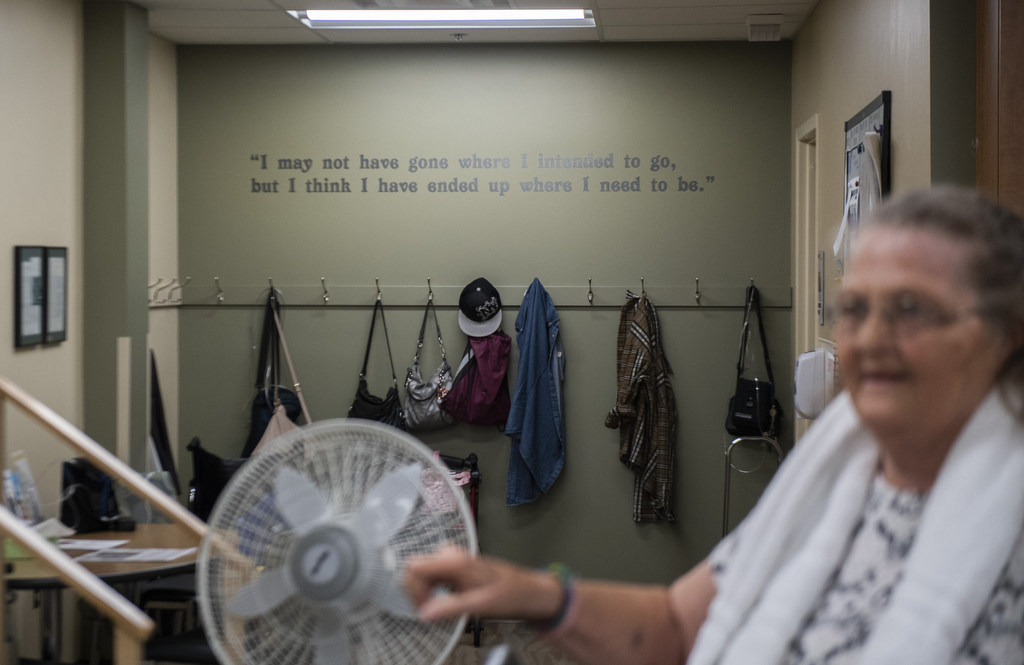

After patients complete the program, many come back to exercise alongside other pulmonary patients for a nominal fee.

Pulmonary rehab provides tremendous benefits, Dr. Cantor said, but it doesn’t actually improve lung function.

“What it does is it improves the patient’s fitness level so that their lungs have to do less work for a given level of activity, so they’re less short of breath,” he said. “Just about everyone feels a lot better and can do more.”

These improvements in fitness add up to fewer pulmonary flare-ups and hospitalizations, lower rates of depression and an overall improvement in quality of life for her participants, Adams said.

Family ties

For Veltkamp, her sister Jennie Magoon, and their cousin Debra Elder, pulmonary rehab is a family affair. Both sisters are COPD patients, while their cousin has shortness of breath caused by both asthma and a diaphragm problem. Doctors for all three women referred them to United Hospital’s pulmonary rehab program. Other relatives share the sisters’ COPD diagnosis.

The prevalence of COPD in the family isn’t surprising when you consider the era in which they grew up.

“Every one of us that has it has smoked. I honestly and truly believe it was our smoking that was 90 percent of the cause,” Veltkamp said. “Everybody you knew smoked. Even when you went to the doctor—even the doctor smoked. … But nobody knew back then, 50 years ago, how bad it was.”

She remembers the day she quit, in 2002. Something her 3-year-old granddaughter said as she lit up stopped her in her tracks.

“She said, ‘Grandma, why you want to leave me?'” Veltkamp said.

Her other grandma, also a smoker, had recently died.

“And that was it. I threw that cigarette away, and every time I wanted one I’d see her face. … She is the reason I quit.”

Magoon quit a year and a half ago using a smoking cessation medication. A self-proclaimed couch potato, she’s proud of what she accomplished in pulmonary rehab and plans to keep exercising.

If she slacks off, Veltkamp will be on the phone encouraging her sister to keep at it. She can’t accept the alternative—for her family or herself.

“It’s not going to get better. That’s just the nature of the disease,” Veltkamp said. “But how fast it progresses is kind of going to depend on me. I can either just sit here and let it take over, or I can fight back.”

With her tight family circle, she has too much to live for to take COPD sitting down.

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>