Henry Dai can truly say he has crushed cancer.

The 17-year-old celebrated his remission by destroying a replica of the tumor that once grew in his chest.

In a room at Spectrum Health Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital, Henry raised a sledgehammer and slammed it down—crash! boom! bang!—multiple times, smashing the tumor to smithereens.

“It felt great,” he said. “It’s like this feeling that I really beat cancer—but literally, as well.”

The cancer-crushing celebration marked a first for the pediatric hematology-oncology program at Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital.

“We wanted to signify the destruction of this evil he has been fighting,” said David Hoogstra, MD, a doctor in the pediatric hematology-oncology fellowship program. “It went really well.”

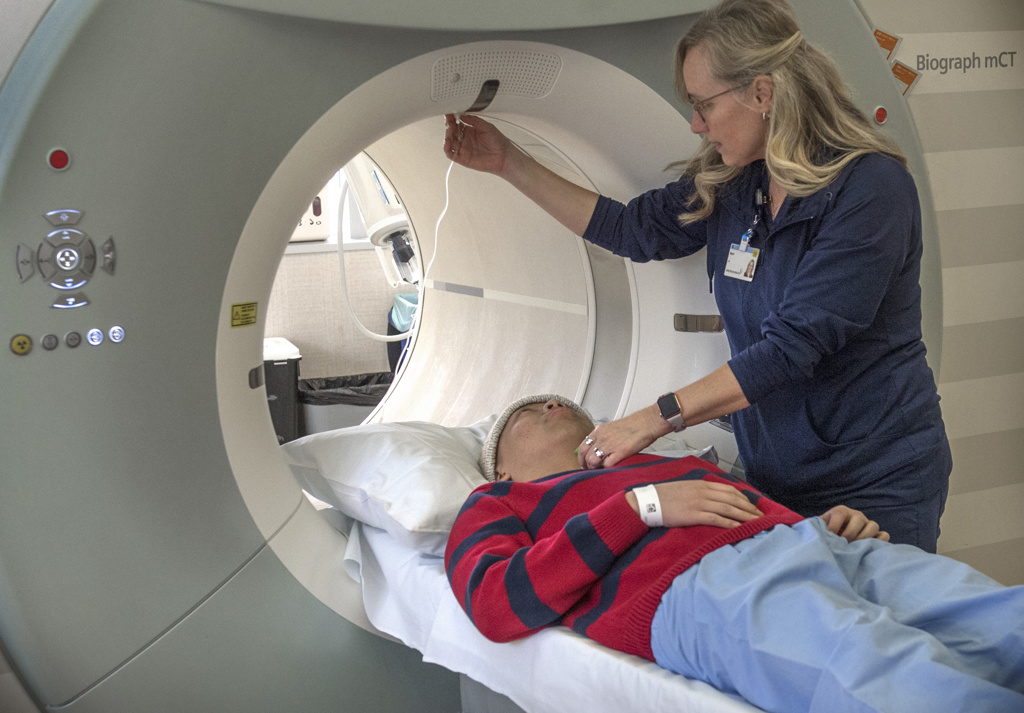

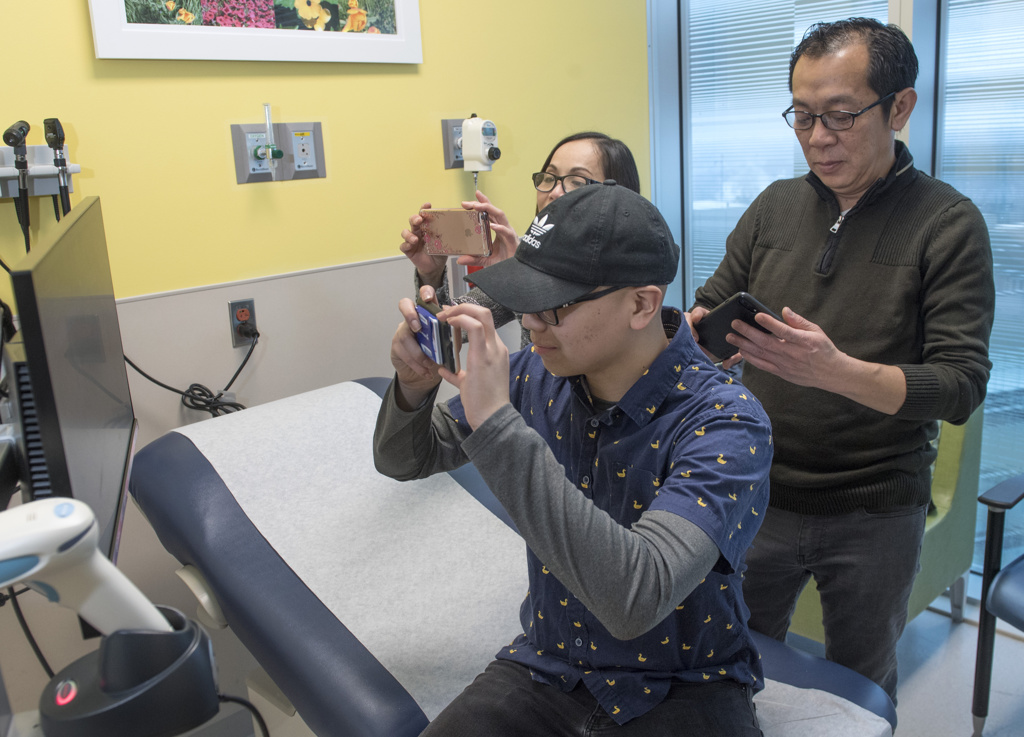

Shortly before the celebration, Henry and his parents met with Dr. Hoogstra to discuss the results of his recent PET scan.

He showed them two scans, side by side. In the one taken before treatment, the tumor appeared as an orange blob near his heart. In the one taken earlier this week, the tumor was gone.

“It has melted away,” Dr. Hoogstra said. “Your scans are clean. They’re clear.”

Henry and his parents welcomed the news with relief.

“That’s amazing,” said his mother, Truc Nguyen.

Shocked by his diagnosis

Henry traced his first signs of lymphoma to late May 2019—exam week of his sophomore year at East Kentwood High School.

He had a bad cold, and that seemed to develop into asthma. After several months of treatment, he still struggled.

In August, during marching band practice, he felt too sick to march.

His doctor ran a blood test and referred him to Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital.

After more scans and tests, Henry sat down with his doctors and learned he had lymphoma, a cancer of the lymphatic system.

He felt numb when he heard the diagnosis.

“It was not a denial kind of thing. I just didn’t feel anything,” he said. “I knew it was serious. But I was too shocked.”

A bright student with a passion for science and math, Henry wanted to focus on the facts about his illness and the plan for his treatment.

Three days after classes started for his junior year at East Kentwood, Henry began a four-month series of chemotherapy treatments.

Every three weeks, he arrived at Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital on a Friday. He received continuous chemotherapy for the six days.

On Wednesday, he left the hospital. He spent 2 ½ weeks at home before returning for his next session.

In handling that demanding schedule, Henry had support and prayers from family and friends, said his father, Luan Dai.

And he encouraged his son, saying, “You’re young. You’re strong. Your mind is strong. You can get through anything.”

Big plans

Henry has long had big plans for his future. After high school, he hopes to attend the University of Michigan or an Ivy League school.

Determined not to let cancer throw his academics off track, he took a full course load at school, including four advanced placement classes.

He continued to play alto saxophone in the school band and the jazz band.

And despite the chemotherapy regimen and 26 absences from school, he finished the semester with a stellar report card: 5 A’s and one A-.

“I am so proud of him,” his mother said.

Proud, but not surprised.

She said Henry has always been a highly motivated student.

He draws inspiration from his parents, who came to the United States from Vietnam in 2000.

“My parents are immigrants and they worked really hard to get to America,” he said. “It would be a waste if I didn’t make an effort, too.”

Henry’s tenacity and kind nature impressed his medical team.

“I have been continually amazed by the grace and courage he demonstrates,” Dr. Hoogstra said.

“In six months of intensive chemotherapy, I could count on one hand the number of times Henry had a negative thing to say. He is just not a complainer.”

During his inpatient stays, Henry passed the time by doing homework. He received tutoring to cover the calculus classes he missed.

“Henry would request to be the first patient seen on his day of discharge, so that he could get to school as soon as possible,” Dr. Hoogstra added.

A unique way to celebrate

As Henry neared the end of his treatment, Dr. Hoogstra began to think about the tumor-smashing celebration. When he was a medical student, he heard about another patient doing something similar.

He ran the idea past Henry, who agreed enthusiastically.

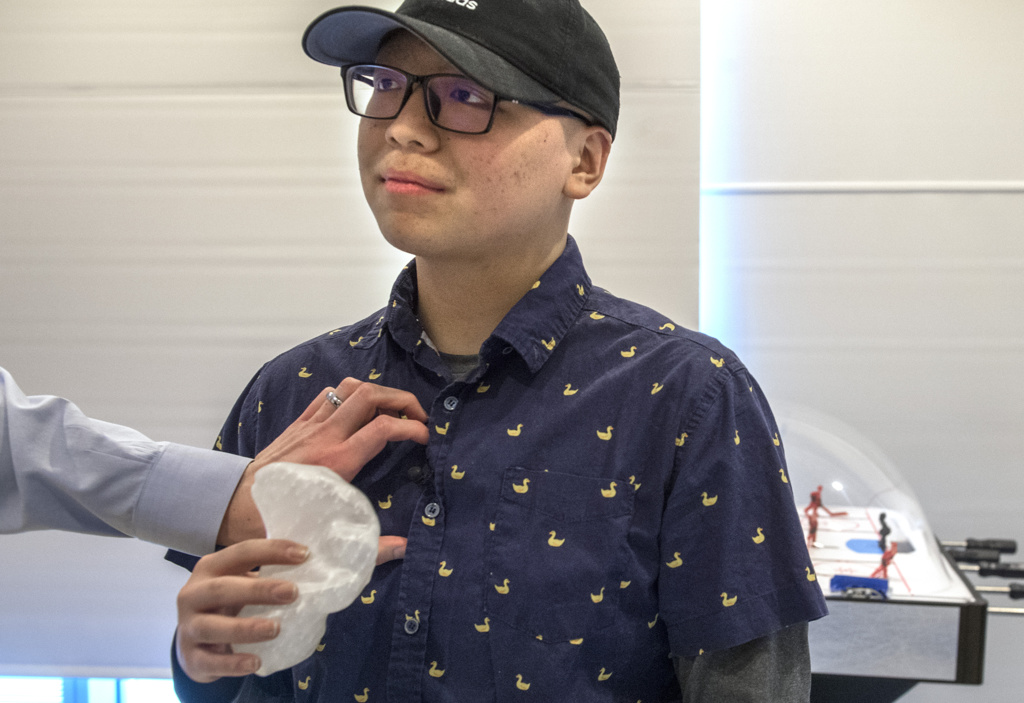

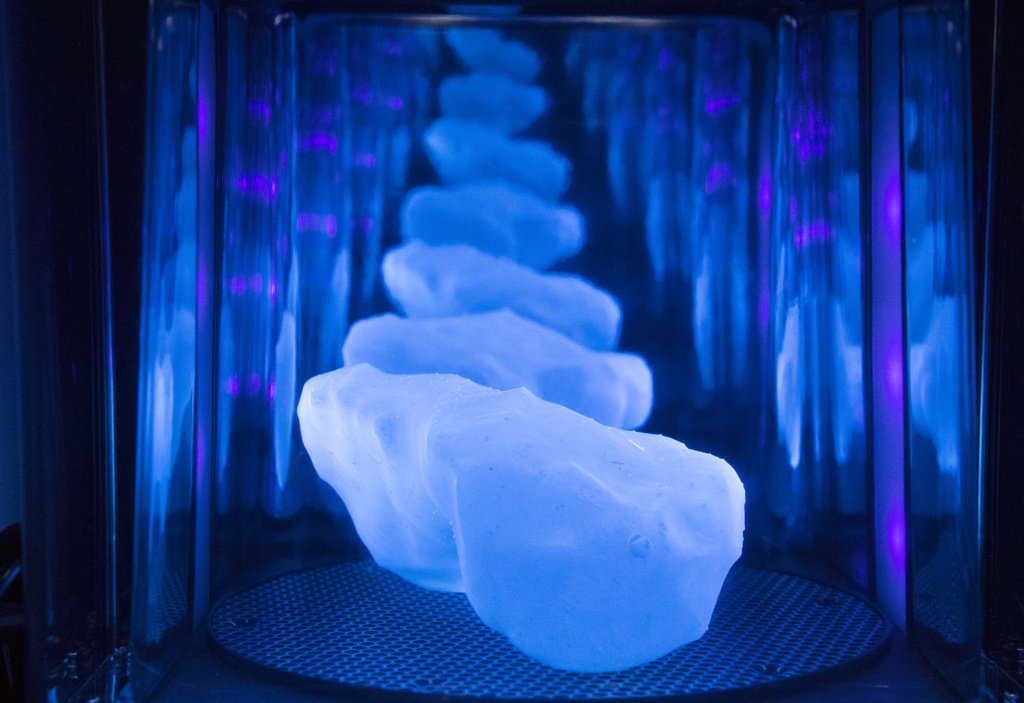

To create the replica, the pediatric hematology-oncology department tapped the 3D printing expertise of the Congenital Heart Center of Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital and Spectrum Health Innovations.

Innovations engineer Eric Van Middendorp, cardiac sonographer Jordan Gosnell and clinical research nurse Bennett Samuel created the models.

They experimented with several materials before settling on a thin, hard plastic that would shatter in a satisfying way.

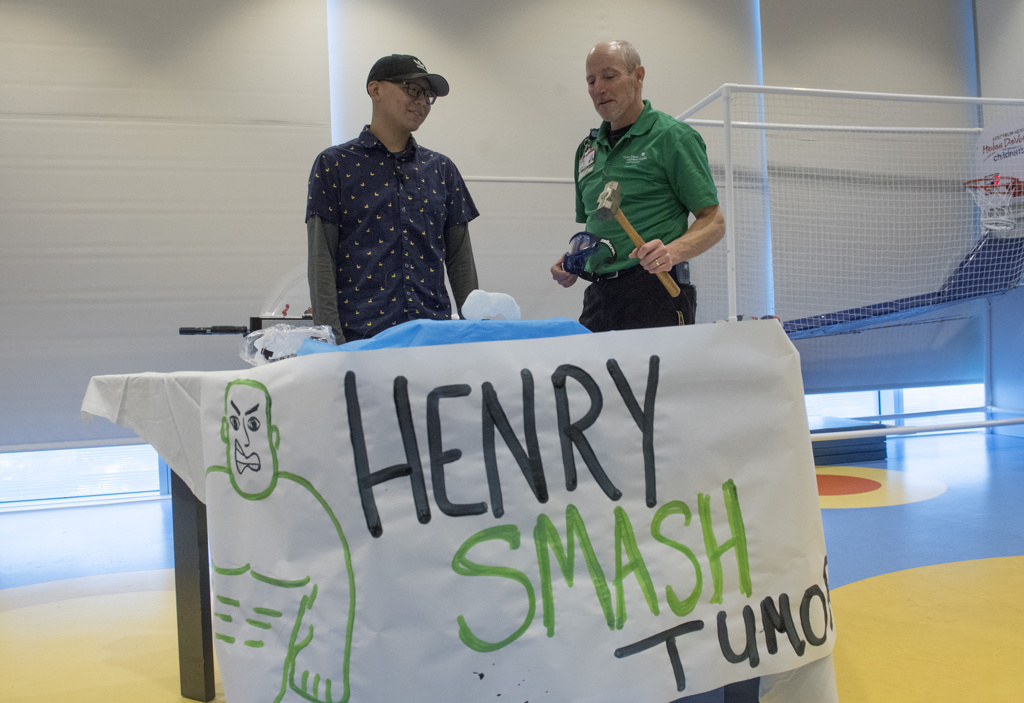

On Friday, Child Life specialist Rhys VanDemark set up a table with a block of wood, covered by a sheet, in a playroom on the 11th floor of the hospital.

On it he set the tumor model, a lumpy white hunk of plastic about 5 inches long and 3 inches wide.

Henry put on safety glasses and gloves.

His parents and medical providers began the countdown: 10, 9, 8, 7, 6, 5, 4, 3, 2, 1.

Henry swung the sledgehammer.

Thunk! He smashed through the tumor into the wood block. He kept swinging until he reduced it to a thousand tiny pieces.

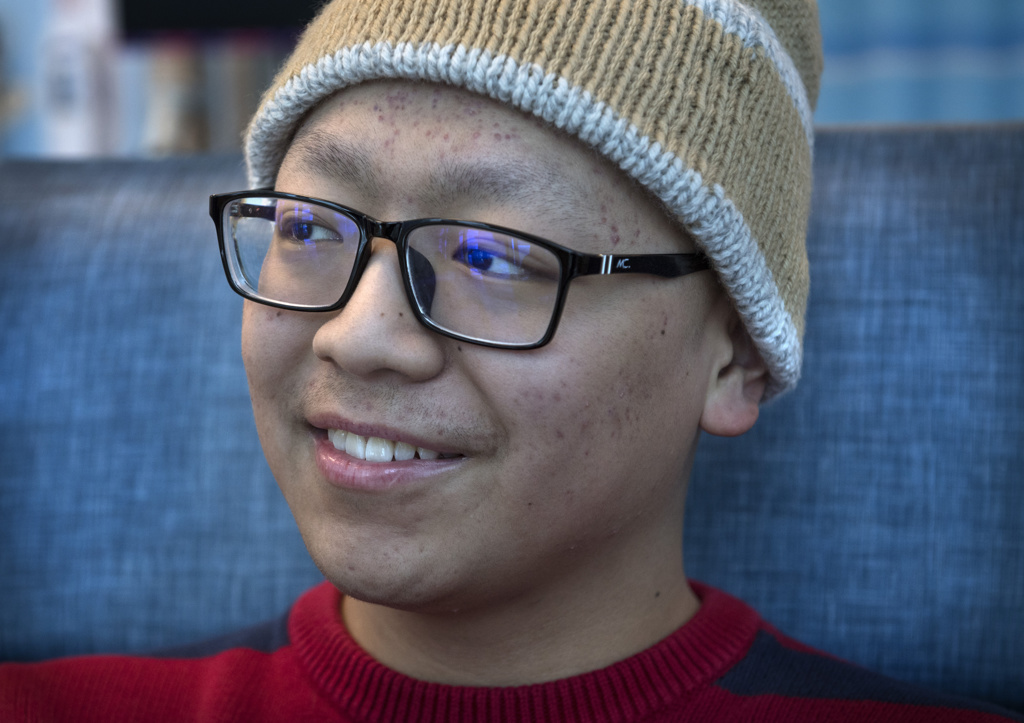

And then he looked up with a smile.

A healing moment

Such end-of-treatment rituals are important for emotional and psychological healing, his caregivers said.

“We are here at Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital not just for physical healing, but for holistic healing of our patients,” Samuel said.

“I think just connecting the external action of smashing the tumor to being internally healed just makes it real for Henry.”

Young patients, and particularly teenagers and young adults, feel a loss of control as they go through cancer therapy, James Fahner, MD, the division chief of pediatric hematology-oncology at Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital.

“To really be able to take ultimate control over your disease has to be cathartic,” he said. “It has to be an amazing closure for what he went through.”

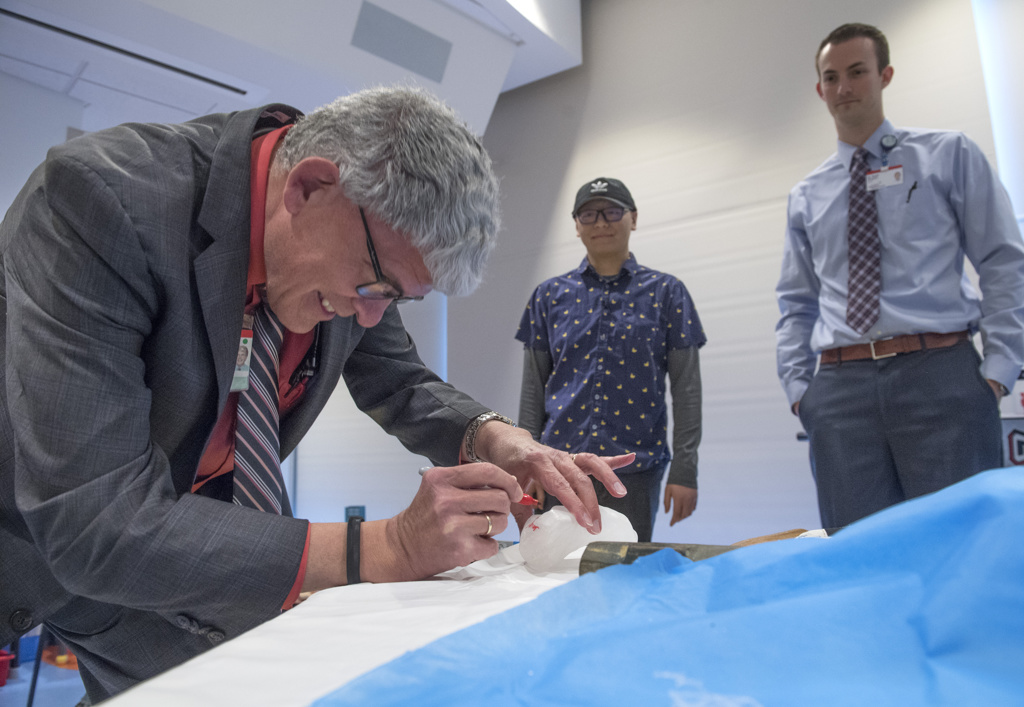

After he obliterated the tumor model, Henry received a second copy of it to take home. He asked his medical caregivers to autograph it.

Looking ahead

His experience battling lymphoma has prompted Henry to consider a change in career goals. He once planned to become a technology engineer or work in a computer-related field.

“After being in the hospital a while, I am thinking something medical-related,” he said. “Maybe cancer research.”

After the tumor destruction was complete, Henry looked forward to another event.

The next day was the Vietnamese Lunar New Year, celebrated with family gatherings, feasts and gifts of red envelopes containing “lucky money.”

“We are ready for the celebration of a new year,” his father said.

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

I loved this story. what a great idea to smash the tumor. High fives to Dr hoogstrate for a great idea and for child life for following thru with the idea

It was a great moment for Henry — and his parents, too. It involved quite a collaboration from a lot of people to make it work. I think Dr. Hoogstra was as delighted as Henry at how it all came together.

Reading this gave me chills. The size of that tumor! The timing…what a celebration that was on the Lunar New Year. What an incredible collaborative by Peds Hemoc, Engineers, Research Clinicians and Child Life. So much to be proud and grateful for. Well done, HDVCH! Congratulations and Chúc Mừng Năm Mới, Dai family!

Brilliant news for Henry! So thankful! And what a great way to celebrate . . .

Congratulations Henry!!! What a great story of your journey. I can only imagine the great impact you will have as an adult, regardless of your career path!!