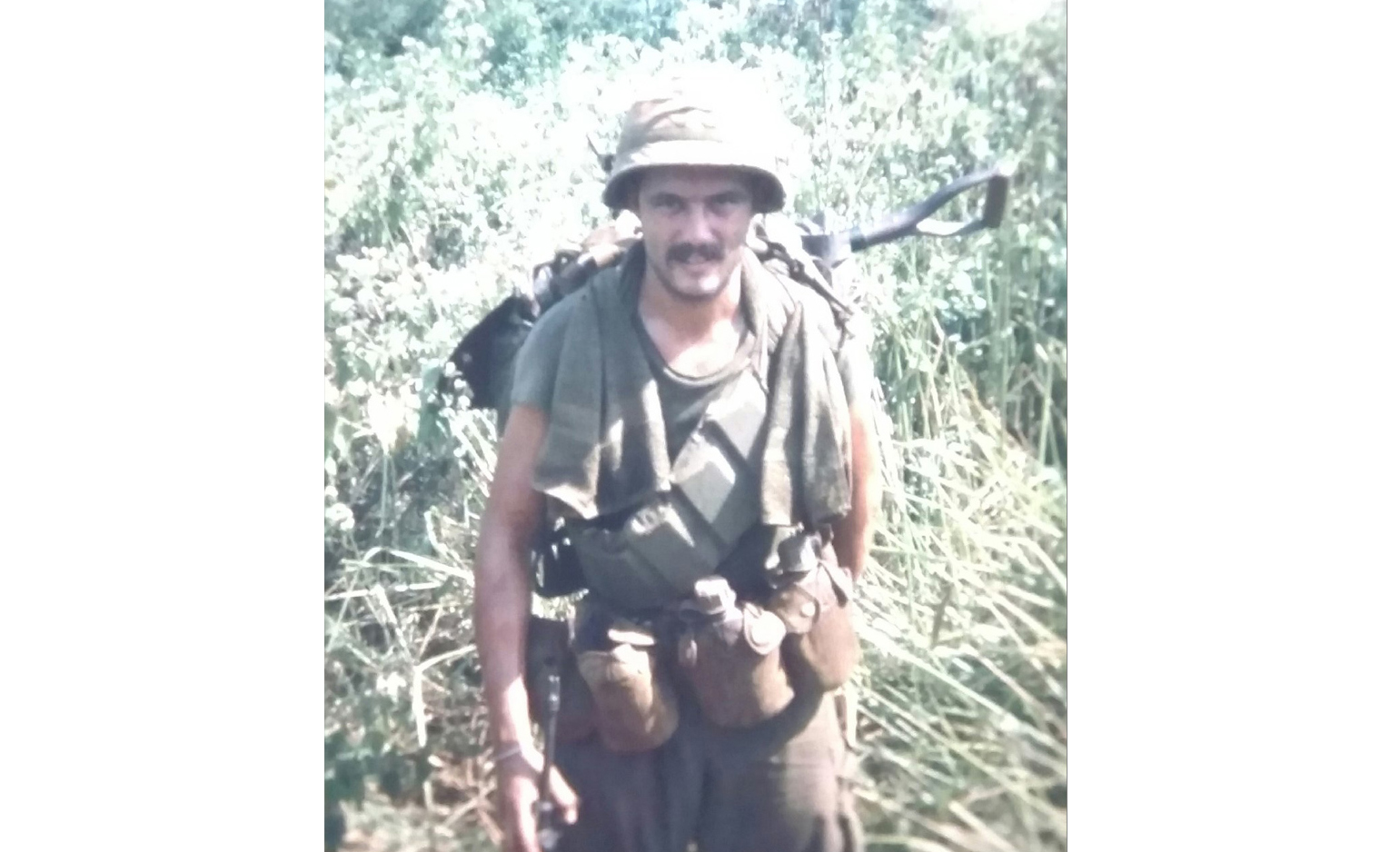

George Welte, 75, is keenly aware of just how close he came to death.

His problems started in earnest about five years ago, in his early 70s. After playing golf for decades, he began encountering serious trouble on the courses.

“It seemed like, every year, it became harder to breathe when I walked the hills of the golf course,” the retired school guidance counselor said.

His doctor took some X-rays of his chest and sent him in for a stress test.

“I hadn’t been on the treadmill for a full minute before I had to stop,” he said. “They had to stop the test.”

He initially underwent a heart catheterization but this turned into a triple bypass surgery once doctors discovered the extent of blockage.

That wasn’t the end of things.

During his post-op examination, a CT scan revealed trouble in his lungs.

The doctor called it “honeycombing.”

In December 2016, doctors diagnosed him with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. The scarring and thickening of his lungs had made it increasingly difficult for him to breathe.

‘I became resigned’

Life expectancy after a diagnosis of pulmonary fibrosis runs the gamut, but it can often be tragically short—sometimes as little as three to five years.

Medical advancements and new medicines can help combat the symptoms, but sometimes the only solution is a lung transplant.

Welte’s dilemma? Doctors told him his age made him a difficult candidate for a transplant.

“The doctors I saw before I came to Spectrum Health told me a lung transplant was my only hope, but that at 73 I was too old for a transplant,” he said.

So he followed a regimen of medications.

For a year and a half, that slowed the progression of the disease.

But he knew it couldn’t be cured.

In 2017, he and his wife, Krista, went on a vacation out West. They spent some time in the mountains, where the higher altitudes exacerbated his breathing problems.

By the time he returned to his home in Owosso, Michigan, he had to use oxygen treatment to ease his breathing.

“I used a portable, 2-liter oxygen tank that I leased from a medical supply company,” Welte said.

That soon lost its effect.

In December 2017, his pulmonologist told him he had perhaps six months to a year to live.

Nothing more could be done.

“So I became resigned to that,” Welte said.

Never too old to hope

Welte learned that age 65 was the average cutoff for lung transplants.

His age then? 74.

Doctors told him a surgery of that type would likely prove too grueling for someone his age. And organ donations were too few.

About that same time, he began visiting a site called Inspire.com, connecting patients with each other and with caregivers—to ask questions, compare answers and banter about a range of health issues.

“It was in a chat room on Inspire that I met Charlie Bell,” Welte said. “I later learned that he had a lung transplant in 2018, too, the day before I did. He had it at Spectrum Health.”

Welte learned about the Spectrum Health Richard DeVos Heart and Lung Transplant Program.

“I wrote a letter to the program,” Welte said. “And I got a reply. They asked for my records.”

The quick response astounded him.

Just like that, someone showed interest in his case—and they didn’t just turn him away.

A candidate

In March 2018, Welte visited Spectrum Health lung transplant pulmonologist Anupam Kumar, MD.

They talked about his chances.

Suddenly, he had one.

“We are one of the few programs to consider patients for lung transplants past the age of 65 or if they have undergone a previous surgery like triple bypass,” Dr. Kumar said. “George had been told he was too old, but we had done a transplant on someone a year older than him.

“We look at the whole patient, not just the age,” Dr. Kumar said. “And George was otherwise in good medical health.”

To confirm this, Dr. Kumar put Welte through a battery of tests. He gathered all his health data to ensure he was healthy enough to undergo surgery.

“I had my previous doctor send test results to Dr. Kumar, but I wasn’t hopeful,” Welte said. “Frankly, I was giving up.”

Then he got the news.

“The next morning, Dr. Kumar called and said I was a good candidate for transplant evaluation.”

A day to remember

For the first time in a long time, Welte felt his hopes soar.

In October 2018, he underwent five days of various health tests.

“I think there must have been some 15 tests,” he said. “Blood tests, pulmonary tests, swallowing tests to be sure I wouldn’t aspirate during surgery.

“And then one more test: I had to have a colonoscopy to make sure I didn’t have any polyps.”

On Nov. 5, 2018, while enjoying dinner with friends, his cell phone rang.

He learned he passed all his tests and was now on the donor list.

“I almost started bawling,” he said.

The next call—at 4:40 a.m., Nov. 11, 2018—proved even better.

For this Vietnam vet, it held special meaning because it was Veterans Day.

“They said, ‘We have a lung for you,’” Welte said.

The long drive from the Weltes’ home in Owosso to Spectrum Health in Grand Rapids felt incredibly short.

“When I got to Spectrum Health Butterworth Hospital, I still had to wait as they had to do a dry run with the lung to make sure it was good,” Welte said. “So I didn’t know for sure until the last moment.”

It was a right lung only. Doctors deemed it healthy.

Dr. Kumar said, “Most patients can function well on one lung. And we can save another life with the second lung.”

About seven hours later, Welte woke up in recovery with a new lung in his chest. Dr. Kumar told him the surgery was uneventful—just what he wanted to hear.

Taking on the hills

By the next day, Welte was taken off oxygen and breathing on his own. Doctors placed him on medication to help his body accept the new lung. He’ll have to take the medication for the rest of his life.

Spectrum Health heart and lung transplant coordinator Megan Gates, RN, met Welte in his hospital room to talk about his care after surgery.

“We go over what he should expect when he goes home, provide general education on transplants,” she said. “Then I see George when he visits the clinic for checkups.”

Gates coordinates Welte’s care with a team of transplant specialists who ensure the success of not only the surgery but his life afterward, too.

She monitors his medication through blood work and keeps an eye on white blood cell count, which can hint at infections. Gates also oversees these lab tests to monitor his kidney function, which is very important after transplant because of the immune suppression medications.

Nine days following surgery, doctors sent Welte home.

He and his wife decided to stay at the Renucci Hospitality House next to the hospital for the first week afterward, just to stay close to medical care should he need it.

He didn’t.

“George is doing amazing,” Gates said. “He’s done all the hard work of recovery from a transplant.”

Welte chuckled.

“I’m kind of a whiny guy, but I healed good,” he said.

On April 10, 2019, he went golfing.

It rained a bit and the course got muddy, which stalled his golf cart.

“I got out and walked the golf course hills that day,” he said. “And I’ve been walking ever since.

“This journey has been a miracle of increments,” he said. “It took many steps to make this transplant happened, but even with all the risks involved, it was all worth it for one day of easy breathing.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

This was an amazing & inspiring story because I have COPD. I am finding it harder to breathe. Thank you for this great true story.

I met this man last summer. I was in Owasso to visit my friend Kay. All of the Welte’s are amazing people. George seems to be doing really well and is such a nice man.