Doug Leland isn’t one to jump into surgery just because a doctor advises it.

For this Detroit Lions fan and former Saranac High School football coach, big medical decisions require a game plan. You need to do the research and look at the options before you can call the play.

This was Leland’s mindset when he took the advice of his family doctor and visited a Grand Rapids, Michigan, urologist in early 2013.

Evidence pointed to an enlarged prostate. For one thing, the physically fit 51 year old, a retired state corrections officer, had found himself in a couple of unexpected must-urinate-now situations. Then a blood test showed his prostate-specific antigen levels were above normal.

Elevated PSA levels indicate swelling in the prostate gland, which is sometimes caused by cancer.

The urologist did a biopsy, which confirmed the presence of prostate cancer. In discussing the biopsy results with Leland and his wife, Angela, the doctor said he wanted to perform surgery without delay.

“Right away, right now, it’s got to come out,” Leland said, paraphrasing the doctor.

Focused approach

Leland called a timeout.

Conversations he’d had with his family doctor and other men had taught him that removing the prostate wasn’t necessarily the only option—or the best—for a man his age.

He told the urologist he wanted a second opinion. That’s how Leland ended up at the Spectrum Health Cancer Center at Lemmen-Holton Cancer Pavilion, where he met with Eric Buth, MD, a radiation oncologist.

It was Dr. Buth who told Leland about a nationwide clinical trial Spectrum Health had joined that would offer focal therapy—a one-time injection of an experimental prostate cancer drug—followed by five years of regular follow-ups with a research team.

Leland was interested in the research study, so he met with Brian Lane, MD, PhD, and Sue Engerman, RN, members of the team running the clinical trial at Spectrum Health, to learn more about it.

True to form, he and his wife asked a lot of questions and took careful notes.

“I always want to know what my options are and then make an educated decision,” Leland said.

Leland enrolled in the study. A month later he received his study drug injection, targeted to the area of his prostate where the cancer was found. From then on the plan was active surveillance: a recurring schedule of lab work, physical exams, imaging and biopsies.

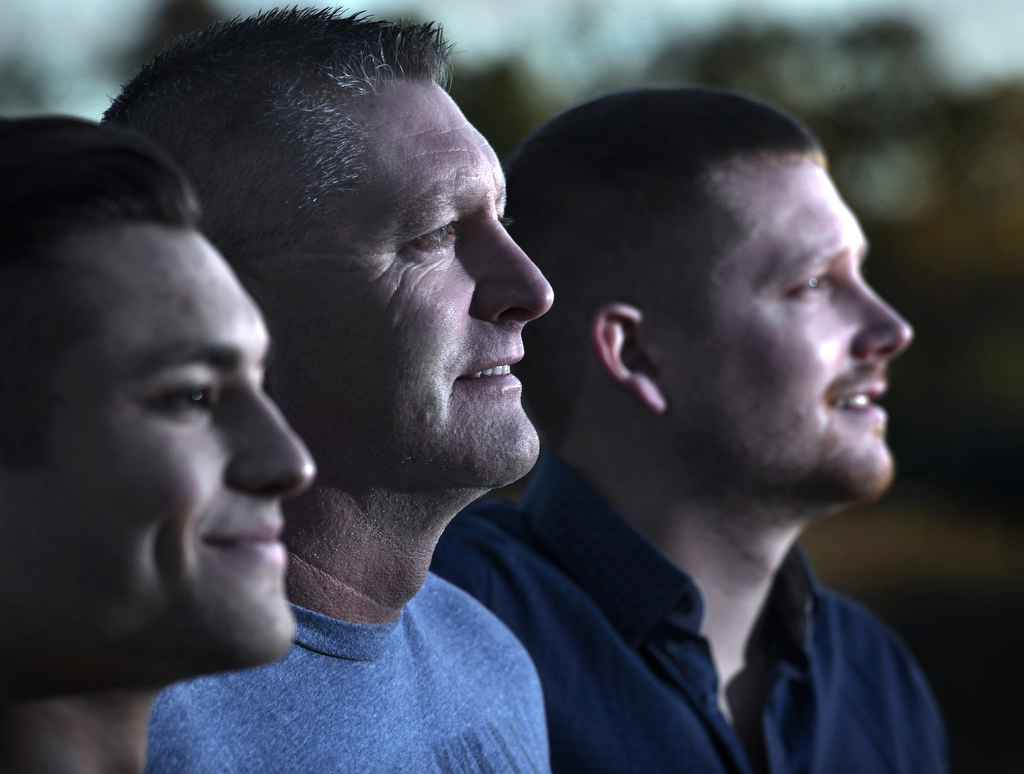

“The reason I participated in the study is that I have three sons and a grandson and five brothers,” Leland said. “So hopefully, no matter what happens, something good will come of this for somebody.”

Ups and downs

Six months after treatment, Leland received great news: Biopsy results showed his prostate to be cancer free.

For the next several months, things looked good. At his follow-up appointments with research nurse Engerman, Leland’s exams and labs were normal.

Then, in May 2015, a year and a half after the study drug treatment, Leland got the news no one wants to hear.

The cancer had returned and his PSA levels were on the rise.

Because the study drug wasn’t approved for injection a second time, Leland went back to Drs. Lane and Buth to explore his options.

For a long list of reasons, Dr. Buth didn’t recommend radiation therapy. Instead, both doctors said Leland would be better off in the long run if he had his prostate removed sooner rather than later.

“Dr. Lane was good about it, as far as allowing us to make the decision ourselves but keeping us informed and educated about everything,” Leland said. “He told me, ‘I want you to have all the facts so that no matter what you decide to do, you will know all the options.’”

Hoping for the best

Using this information, Leland and his wife opted for the surgery. His prostate will be removed Nov. 19, three years after he noticed the first symptoms.

“Doug is a good example of a conservative approach to the management of prostate cancer,” Dr. Lane said. “The amount of treatment is targeted to the amount of cancer—and only if things progress do we take a more aggressive approach.”

What does Leland think, looking back?

“I’m pleased with the route I chose,” he said. “It postponed the surgery by a couple of years.”

In the meantime, he said he hopes the researchers can learn something from the study.

After his operation Leland will have to take it easy for a few months—no heavy lifting, no construction projects, no running. But his recovery could be easier than it is for most men because of his age and overall physical condition.

“I’m OK with it,” he said of the upcoming surgery. “Actually it’s been much harder for the family. But we’re hoping for the best.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

Thank-you for sharing this story about this great guy and his beautiful family. This is not only a heart-warming story, but it is also informative. Stories like these help others, who are facing the same diagnoses, to make the tough decisions needed for treatment. People need to know that they have options.

This family is a blessing to so many. God didn’t bring them this far..to leave them now. Stay tuned for his next miracle, ..its going to be GOOD !