On a Saturday night in June 2020, Diane Carter, 52, helped her mom into the passenger seat of her Lincoln sedan. After checking her GPS for the fastest route to the local ER, she pulled away from the house.

Diane’s mom felt ill and Diane wanted to get her checked out.

Halfway into their 15-minute trip, life would forever change for the two women and their families.

As Diane drove through an intersection on a green light, a car hurtling down the cross street hit her broadside going nearly 100 mph.

“You know how they say that your life can change in the blink of an eye? Well, it can. They don’t make that up,” said Diane, a wife and mother of two from Allendale, Michigan.

“It certainly has made me grateful for every day.”

Diane remembers little from that night or the grueling weeks that followed. She relies on her husband, John, to fill in the details from the early days of her trauma.

John has recounted his wife’s story so often he has her list of injuries memorized, from head to toe.

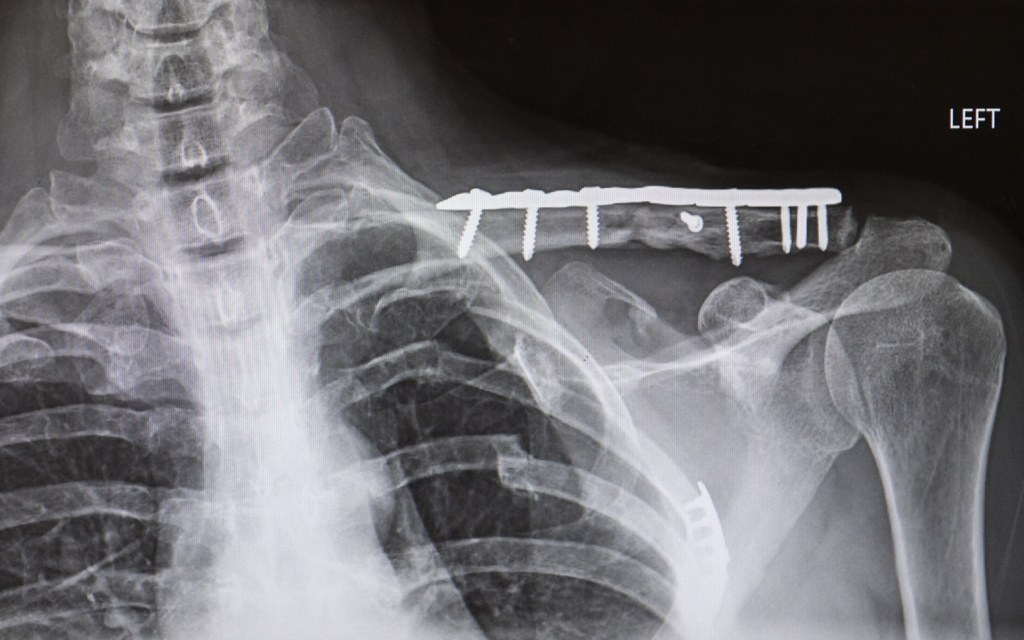

Major concussion. Serious cervical spine injury. Damage to the four arteries leading to the brain. Fractured left collarbone. Fractured left shoulder blade. Twelve fractured ribs. Punctured lung. Torn diaphragm. Ruptured spleen. Lacerated liver. Injuries to her thoracic and lumbar spine. Fractured right forearm. Fractured pelvis. Plus, broken teeth and several other minor injuries.

Level 1 trauma

The severity of Diane’s injuries and the force of the impact led the EMS team on the scene to designate her case a Level 1 trauma.

Before she arrived at the Spectrum Health Trauma Center at Butterworth Hospital, a team of roughly 30 people had assembled in the trauma bay, ready to receive her, according to Alistair Chapman, MD, who specializes in acute care surgery.

“We’re there and we’re gowned up before the patient arrives so that we can provide time-sensitive care,” Dr. Chapman said. “Doing Level 1 trauma care is all about providing time-sensitive care for time-sensitive injuries.”

Following the Advanced Trauma Life Support protocol, the trauma team—including emergency physicians and technicians, nursing staff, radiology technicians, trauma surgeons, a blood bank representative and others—did an initial evaluation of Diane’s injuries and sent her for a head-through-pelvis CT scan.

The scan confirmed she had suffered “significant polytraumatic injuries,” Dr. Chapman said.

In such a case, the trauma team zeroes in on saving the patient’s life.

“That night, the first priority was to fix her diaphragmatic hernia,” Dr. Chapman said.

The diaphragm, a muscle that separates the abdomen from the chest, had torn open, allowing her abdominal contents to spill into the chest cavity.

During emergency surgery, doctors “pulled the contents that belong in the abdomen out of the chest, put them back in the abdomen and repaired her diaphragm,” Dr. Chapman said. They also removed her damaged spleen.

After surgery, Diane went to the ICU, where she remained on a breathing machine because of her chest wall injury. The ICU team watched her closely to see how she would progress.

In the meantime, John had tracked down his wife at Butterworth Hospital.

His search had begun after his father-in-law called to say there’d been a crash and Diane’s mother had been transported to another hospital.

She, too, underwent emergency surgery that night.

For Diane’s mom, however, internal injuries proved too critical to overcome. She died 10 days after the crash, as her daughter waged the fight of her life in a hospital room across town.

Months later, the family still struggles to comprehend their loss.

“My mom and I were very close, and she’s gone,” Diane said. “It’s still—it’s just not there. But it’ll come.”

Six days, four surgeries

When John reached his wife in the wee hours of the morning after the crash, her future hung in the balance.

“They brought me down to see her, and she was on a ventilator—more tubes and various machines than I had seen on anybody, ever,” he said.

“They said, ‘We’re not going to do anything more to her for the next 24 hours. … We’re putting a team together to figure out how to put her back together if she makes it the next 24 hours.’”

She made it through the next day.

By then, James Stubbart, MD, a spine specialist, had assessed Diane’s neck injuries and concluded he could treat her with a cervical collar rather than spinal surgery.

This assessment cleared the way for a major orthopedic surgery to repair a fracture in the right side of Diane’s pelvis and another in her right ulna.

After a successful second surgery, the multidisciplinary trauma team defined the next priority: helping Diane to breathe on her own. That would require a third surgery, this one with Dr. Chapman and his colleague Charles Gibson, MD.

“The team didn’t think they would be able to get her off the breathing machine without repairing the chest wall,” Dr. Chapman explained. “She had a lot of rib fractures on the left side, and my goal was to restore the ones … that primarily impact the mechanics of breathing.”

Drs. Chapman and Gibson plated five ribs on Diane’s left side, essentially reconstructing her chest.

By the time John arrived at the hospital the next day—three-plus days after the crash—his wife had come off the ventilator and lay breathing on her own.

It would take one more operation before her lengthy rehabilitation could begin: Two days after the rib fixation, Diane had her fourth surgery, an orthopedic procedure to repair her left collarbone.

This wrapped up what Dr. Chapman calls Stage 2 of a trauma patient’s pathway, the phase in which doctors decide how to repair the injuries that remain once the initial, lifesaving phase has passed.

“That’s a very calculated move on our part because you can only push a patient’s body so hard, and you have to be very careful about how you time things,” he said. “Intervening on one issue has the potential to have downstream effects on other issues.”

Painful recovery

Diane’s medical team now shifted their focus to her recovery—beginning with pain management.

“There was so much pain radiating from everywhere,” John said.

“They would ask, does it hurt? Do you hurt? ‘Yeah, everything hurts.’

“She would doze for 20, 30 minutes at a time and then she was awake again. Getting her to sleep and letting her body heal was a huge thing.”

These excruciating post-operative days—this is where Diane’s memory kicks back in.

Because although her upper body had sustained more than three dozen fractures, the occupational therapy staff still had to get her up to keep fluid from settling in her lungs.

“Some of my earliest memories—scariest memories—were OT coming in and wanting me to sit up in bed. And then sit up in bed turned into sit on the side of the bed,” she said.

“The pain would make me just want to lose my lunch. The room would just spin and—yeah, it’s hard to even put into words.”

John couldn’t bear to watch his wife suffer during those moments.

“Yeah, during a lot of those times I had to leave. The protective instinct—protecting the one that you love—would be so strong that it’s like, ‘You guys do what you gotta do. I’m going out in the hall.’ And I could hear her scream out in the hallway … a full-out blood-curdling scream.”

The in-hospital therapy program sets patients up for Stage 3 of the trauma journey, the rehab phase. Fortunately, Diane qualified for acute rehabilitation, “the boot camp of rehab,” Dr. Chapman said.

“That’s always the best-case scenario—when we can get patients to that highest level of rehab—because as we transfer them out of the hospital, we know that they’re going to get pushed,” he said.

Three weeks after she arrived, Diane left Butterworth Hospital by ambulance for Mary Free Bed Rehabilitation Hospital.

As it happened, Diane’s discharge fell on the same day as her mother’s funeral. John left the gathering at the church just in time to accompany his wife to her room at the rehab hospital.

For the next month, Diane engaged in daily intensive physical therapy. Though she still felt severe pain and nausea, she brought drive and determination to each session.

“She always seems to have an attitude that ‘I’m going to get through this.’ There’s not really another option for her—‘I’m going to get back to normal life, and I’m going to use my arms and my legs how I would have before this injury happened,’” said Joe Westerhof, PA, who specializes in orthopedic trauma.

Westerhof has seen Diane at her post-rehab visits to the Spectrum Health Multidisciplinary Trauma Clinic, a collaborative office that includes specialists in orthopedic trauma, acute care, burn, physical medicine, rehabilitation and neuropsychology.

Both Westerhof and Dr. Chapman have marveled at the speed of her recovery.

“The first time I saw her in the office, she was in a wheelchair but getting around. And then the second time I saw her in the office, she walked in. That was just awesome,” Dr. Chapman said. “She just raced through her recovery in a really phenomenal way.”

Dr. Chapman credits Diane’s swift progress to two factors: her positive outlook and having John by her side.

“Her sense of optimism that there’s a good future, there’s a good outcome for her, and having the support of her husband to navigate the tough moments … has really helped her to get through this recovery in a way that’s been very positive and very quick,” he said.

To measure just how fast her recovery has been, John recalled a conversation he had with a doctor in the early days of Diane’s hospitalization.

“I asked at one point, ‘Just give me a timeline, just something that I can grasp onto. What are we talking? Years?’ And the doctor told me that Christmas would be a good time, a realistic time, to shoot for her to be home—Thanksgiving if things go really well,” John said.

Instead, Diane went home July 21, four months earlier than anyone expected.

Home to her family and friends, a career that she loves and the hope of again teaching in the children’s ministry at her church.

Though she still has months of outpatient physical therapy ahead of her—and had two unexpected surgeries in December to deal with scar tissue and gallbladder issues—she’s as much in awe of her prospects as anyone.

“When I think back on just how traumatic that was, and how I’m (now) able to get out of a chair pretty smoothly, I’m able to go for a walk, I’m able to bend over and pick things up—it’s pretty amazing. It’s pretty remarkable,” she said.

What’s even more remarkable? That she’s alive to tell her story.

“If you look at the number of ways where I shouldn’t be here—and then if I were here, I shouldn’t be talking; and then if I can even be talking, I shouldn’t be walking—It’s really nothing short of a miracle,” she said.

“There are no words in the English language for how grateful I am that God spared my life and put all these amazing people in my path to put me back together.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

What an incredible testimony that Diane has. She is definitely a walking miracle.

God is so good! A great medical team is too.