Kingston Wilson plays catch with a visitor, laughing as he rolls his wheelchair across the room to retrieve the ball.

Stopping at a table, he takes a bite out of a Pop Tart. And then he’s back in the game. “Again!” he cries, as he tosses the ball.

For a 3-year-old boy with spinal muscular atrophy, these moments shine, reflecting extraordinary progress made with help from physical therapy and a breakthrough medication.

“With Kingston, no milestone is a small milestone,” says his mom, Savannah Nanninga-Jensen. “No gain is a small gain for him.”

The path has not been easy. Kingston has been hospitalized about 100 times in his short life.

But his mom marvels at the way he bounces back from each challenge, with a playful spirit and a smile that lights up a room.

“Kingston is just so resilient,” she says. “He has gone through so much and he is so tough.”

Kingston showed no sign of spinal muscular atrophy, a rare genetic disease, when he was born June 14, 2015, at Spectrum Health Butterworth Hospital. He arrived six weeks before his due date, weighing 4 pounds, 4 ounces. After 18 days in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit at Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital, he went home.

Kingston seemed to grow strong and healthy at first, hitting developmental milestones as expected. But at 5 months old, his development seemed to lag. He became sick with colds and pneumonia, and often ended up in the hospital. Savannah began asking questions of his physicians and consulted specialists.

At 1½ years old, Kingston spent a month in the hospital, coping with pneumonia, RSV, coronavirus and rhinovirus.

A couple of months later, Savannah’s search for answers yielded a diagnosis: spinal muscular atrophy.

“I just started crying,” she said.

A gene and a backup gene

Spinal muscular atrophy is a genetic disease that causes progressive weakness of muscles involved in crawling, walking, swallowing, breathing and other functions. It does not affect intellectual development.

The condition is caused by differences in the survival motor neuron gene—called SMN1—which is involved with nerve development and function, says Caleb Bupp, MD, the Spectrum Health medical geneticist who has worked with Kingston and his family.

Next to the SMN1 gene in the genetic code is the SMN2 gene, a less effective form of the gene, which can sometimes serve as a backup.

“The theory is that SMN2 is left over from evolution. That’s why it’s still there—because we don’t really use it,” Dr. Bupp says. “It’s kind of like the doughnut spare tire (for a car).”

Whether a person has SMN2—and the number of copies—determines the severity of their condition. Kingston, with three copies of SMN2, was diagnosed with spinal muscular atrophy type II.

One in 6,000 to 1 in 10,000 children are born with spinal muscular atrophy, according to the Spinal Muscular Atrophy Foundation. One in 50 adults is a carrier of a mutation in the SMN1 gene. Both parents must be carriers and pass on the defective gene for a child to have spinal muscular atrophy.

Neither of Kingston’s parents knew of any family history of spinal muscular atrophy—and that’s common for an autosomal recessive disorder.

“Being carriers probably runs back generations,” Dr. Bupp says.

Even when both parents are carriers, there is still only a 1 in 4 chance that their child will be born with spinal muscular atrophy.

Reason for hope

As she struggled to comprehend her son’s diagnosis and worried about his future, Savannah pinned her hopes on a new development. A few months before Kingston’s diagnosis, the first drug designed to treat spinal muscular atrophy received approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

The medication, Spinraza, improves the ability of the backup gene to make survival motor neurons.

In June 2017, at age 2, Kingston received his first dose of Spinraza in an injection delivered through his lower back directly into the central nervous system.

He received four doses in the first two months. Now, he receives an injection of Spinraza every four months.

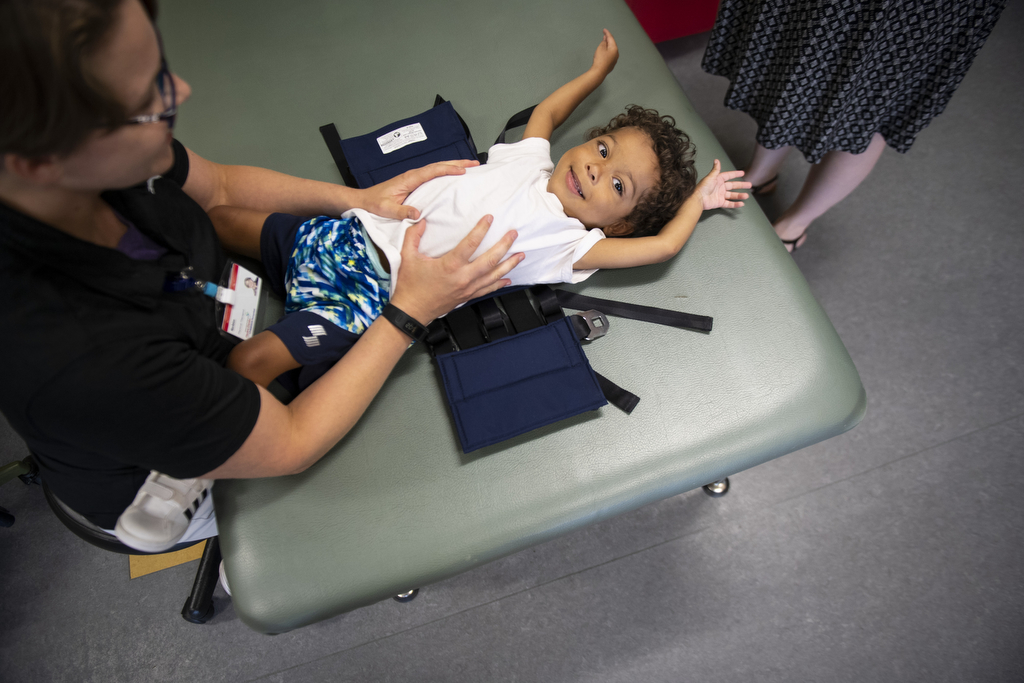

Kingston also began to receive physical therapy every week at the outpatient therapy center for Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital.

Strength through play

Kingston lies on his tummy on a giant ball as physical therapist Robin Fisher gently rolls it side to side.

“Can you lift up your head a little bit?” she asks. “I’m going to help you.”

Head raised, Kingston looks at his mom and his 2-year-old sister, Everly, a grin on his face.

They look like fun and games, but the physical therapy exercises also build the core muscles needed for mobility—to move into a sitting position or to lie down, for example.

“The Spinraza is replacing the (spinal motor neurons) he is missing, which is really, really important for muscle contractions,” Fisher says.

Physical therapy helps him learn to use the strength he has gained to improve his function and mobility. It helps him learn to sit, stand and begin taking steps with a gait trainer.

“Even improving his head control is life-changing,” Fisher says. “And the stronger we can make his muscles around his core and chest, the better he is going to do from a respiratory standpoint, as well.”

With the combination of physical therapy and medication, Savannah has seen Kingston grow healthier and stronger.

For the past eight months, whenever he contracts a cold or respiratory virus, he manages to recover without having to be placed on a ventilator—a rarity for him. He has gone two months without a hospitalization. Again, that’s a big accomplishment.

He used to be able to sit up for only five to 10 minutes. Now he can sit for longer periods—an hour or more at a time.

He raises his hands above his head and throws a ball. In physical therapy, he walks with a specialized walker.

“Kingston is pushing a manual wheelchair, which is huge,” Savannah says. “A lot of kids (with spinal muscular atrophy) have power chairs.”

The disease affects the muscles involved in swallowing, and it can take a long time for him to eat a meal. But his mom is thankful he gets enough nutrition by mouth and does not need a feeding tube.

All those developments add up to better quality of life for Kingston, which means more independence, more time to play with his sister and more fun exploring his interests.

“He loves cars. He has 400 Hot Wheels,” Savannah says. “He likes to swim. He likes Legos. He likes to build things.

“He is so curious, too. He wants to know why things work and how things work. He has so many questions.”

Advocating for her son through his medical issues is a challenge, Savannah acknowledges.

“Being a single mom and having a special needs child is not something you can prepare for,” she says. “I do my best. I definitely have learned new words for my vocabulary.”

For support, she relies on her mom.

For inspiration, she looks to her son.

“Kingston goes through all this and he is a champ,” she says. “He is always laughing. He’s always smiling. He just wins over hearts.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>