Dallas VanDeusen has a world-class smile, and he’s not afraid to use it.

He flashes that grin―joyful and genuine―about a million times a day.

Even when he talks about an injury that left him sidelined for most of a year. And he’s only 13, so that’s a good portion of his young life.

He suffered pain, there’s no doubt. And he lost some mobility and freedom―a tough thing when he already deals with cerebral palsy that affects all four limbs.

Dallas went through a big surgery at Spectrum Health Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital, one that involved “untwisting” his left leg and that required extensive recovery. But he faced it all with a toughness―and a smile―that touched his surgeon’s heart.

It wasn’t easy, Dallas acknowledges. But now, he says, “I can do everything I did before.”

“He’s an incredibly happy kid,” said Philip Nowicki, MD, his pediatric orthopedic surgeon. “He makes my job worth doing every second of the day.”

A seventh-grader at Kenowa Hills Middle School, Dallas has no shortage of favorite activities.

“Coming to school,” he says. “Playing on my iPad. Riding my bike. Playing outside.”

He has completed our family. He has completely changed us.

He roots for the West Michigan Whitecaps baseball team and cheers on the Grand Rapids Griffins hockey team. He plays baseball with the West Michigan Miracle League and races in marathons and triathlons with his uncle as part of a wheelchair team.

It’s the typically busy life of a teenager, though with a few extra challenges and triumphs.

‘He’s been a blessing’

Dallas sits on the couch at his home in Walker, Michigan, with his parents, Mendy and Steve VanDeusen, to talk about his recent big setback and the comeback that followed.

First, they talk about his cerebral palsy. The first indication of a possible problem during Mendy’s pregnancy occurred at 37 weeks. After a bout of stomach flu, she noticed her baby seemed to move less, and then he didn’t seem to move at all.

Her doctor soon delivered Dallas by cesarean section at Spectrum Health Butterworth Hospital. When he arrived, her medical team saw a tight knot in the umbilical cord, Mendy said.

Dallas arrived weighing a sturdy 8 pounds and 2 ounces. Although he had trouble breathing, he quickly recovered and went home on schedule.

He was an easygoing, happy baby, Mendy says. And cute.

“I’m still cute,” Dallas says with a grin.

His mom wraps an arm around him and laughs.

“He’s always been like this,” she says. “He’s very easygoing.”

Dallas was 6 months old when his parents took him to the doctor because he didn’t seem to be meeting developmental milestones, such as raising his head. The neurologist determined he had spastic quadriplegia cerebral palsy―which involves severe muscle tightness in four limbs. His right side is more affected than his left. He also had mild cognitive impairment.

“It was pretty awful to hear,” Mendy says. “We didn’t know what he would be able to do.”

The parents worried about their son’s future, his quality of life and the impact of his condition on the family.

At one point, Mendy wondered, “Would it have been better if he didn’t survive?”

It’s hard to remember that now, Mendy says. Thirteen years later, sitting beside Dallas and sharing laughs and hugs, she talks about blessings of raising “this awesome kid.”

“I cannot imagine not having him,” she says. “He has completed our family. He has completely changed us. I feel like he’s just brought a lot of joy to our family, a lot of laughter.

“He’s been a blessing, for sure.”

Dallas amazes his parents with his compassion for others. If his mom mentions she has a headache, he checks back later to see if she feels better.

His parents also have come to appreciate the fact that Dallas’ condition does not get progressively worse and that therapy and adaptive equipment open up new possibilities. He can push forward and learn new skills.

“You can only get better,” Mendy says. “Dallas is constantly learning.”

Dallas has undergone several surgeries through the years―to straighten his eyes, which were crossed; to put tubes in his ears; and to release the tight muscles on the back of his legs.

Although he uses a wheelchair most of the time, Dallas also gets around with a walker and a bike.

An injured knee

The injury to his left knee occurred in early 2015, as he sat down to watch his beloved Griffins play hockey. His left knee popped out of alignment.

The injury is a common hazard for kids with long-term muscle spasticity, Dr. Nowicki said. The tendon stretches, making the knee cap prone to dislocate.

For kids without cerebral palsy, doctors usually can treat the injury with physical therapy and bracing. But because of the spasticity in Dallas’ leg muscles, any irritation causes the muscles to clench and dislocate the knee.

He’s diligent and persistent. He didn’t let it get him down.

With the knee repeatedly out of alignment, Dallas could no longer ride his bike, walk shorter distances or stand comfortably when he transferred from his wheelchair.

And it was painful.

One option would be to remove the knee cap, Dr. Nowicki said. That would bring pain relief, but would limit his mobility. Dallas might not be able to ride a bike. To stand, he would need more straps for extra support.

Talking with the VanDeusens, he decided to take a more aggressive surgery to straighten the bones and muscles of Dallas’ leg.

In an operation just before Labor Day 2015 at Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital, Nowicki cut the left femur bone just above the knee and brought it out to better meet the groove where the knee cap sits. He took tendons off the knee cap and tied them in a higher position. And he reconstructed the thin layer of tissue that keeps the knee cap in place.

And because the surgery rotated the femur outward, he rotated the tibia and fibula in the calf inward―essentially untwisting the leg to make it straight.

“It’s no doubt aggressive, moving a lot of things around,” Dr. Nowicki said. “The idea was to address all the potential areas that cause (the knee cap) to go out and to fix them.”

The surgery required a long recovery and much physical therapy. Dallas powered through it with a cheerful attitude.

“He went through a lot and he did a lot,” Dr. Nowicki said. “He’s diligent and persistent. He didn’t let it get him down.”

That resiliency impresses Dallas’ dad. He marvels at his son’s smile and positive attitude.

“He never gives up until he’s satisfied,” he says.

In honor of Dallas’ recovery and determination, he was honored as a “Captain’s Kid” at a Griffins game. Attending the game with his family, friends and medical team, Dallas wheeled onto the ice to drop the puck.

The secret of happiness

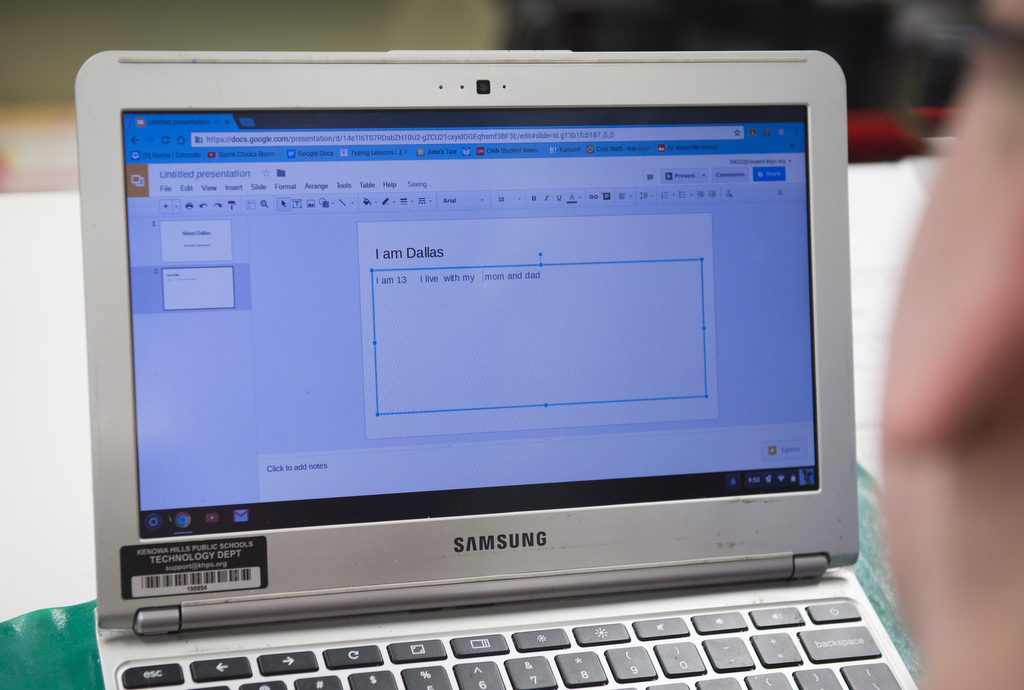

In his classroom at Kenowa Hills Middle School, Dallas begins writing the story of his life, using his left index finger to type the title on a laptop computer: “About Dallas.”

Asked about the favorite people in his life, Dallas quickly responds: “My mom, my dad, my sister and my brother.”

His teacher, Joseph Jorgensen, and his aide, Rose Ford, say he has become stronger and better able to move his legs, stand and use the walker. He still works regularly with a physical therapist at school to boost his strength and mobility.

When they talk about Dallas, both his teacher and aide sound a common theme: They admire his upbeat attitude and joyful spirit.

Asked what makes him such a happy guy, Dallas just laughs. But really, what makes him such a happy soul?

“Because I’m happy,” he says.

And he smiles.

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

You are one amazing kid Dallas. You and Trevor are so much alike in so many ways ♥😊

Agreed! Taylor Ballek and I really enjoyed getting to know Dallas. He is such a great young man.

Wonderful story. Sue, your writing pulls us into the story.

Thank you, Marcy!

this was gr8

Thanks for your comment, Gavin. Dallas certainly is “gr8!”

dallace i hope you get beter and have every thing you wnt

Dallas you’re so upbeat and it makes everyone so happy. I hope all your dreams come true, you really deserve it!

good story Sue, thank you for pointing out how children with disabilities can enrich families. Dallas is one of many examples.