They take temperatures, swab noses, give breathing treatments, stitch up wounds, mop floors and deliver babies.

Under the shadow of a global pandemic, Spectrum Health team members show up day after day to provide hands-on care for the sick and injured. At the same time, they prepare for a surge in patients ill with COVID-19, the disease caused by the highly contagious coronavirus.

At the end of the day, they go home, exhausted.

Still, COVID-19 shadows their steps.

Some undress in the garage. Some at the back door or in the laundry room. They toss their scrubs directly into the washing machine and take a shower.

All to protect their loved ones in case the virus hitchhiked home with them.

It’s a challenge they willingly embrace during this pandemic. They work extra hours, cancel vacations and take on new responsibilities to ensure the safety and health of their patients.

“It’s absolutely what we signed up for,” Michael Tsimis, MD, said. “We have an obligation to our patients and our community to be the ones who are there for them.”

And how can we help?

Stay home. Wash your hands. Practice social distancing. Do what you can to prevent or slow the spread of COVID-19, they urge.

And maybe say thank you once in a while. A bit of appreciation goes a long way.

Meet a few of the heroes working on the front lines at Spectrum Health.

‘I took an oath’

Vivian Romero, MD, walks in the door after a day of work, and her 5-year-old twins rush to greet her. Her husband holds them back as she sidesteps—no contact allowed until she has showered and changed clothes.

A maternal fetal medicine specialist, Dr. Romero cares for women with high-risk pregnancies.

Babies don’t wait for pandemics, so her workload remains as busy as ever. She and the maternal fetal medicine team continue to treat patients, monitor their health, deliver babies, perform cesarean sections and provide follow-up care after delivery.

“I couldn’t be prouder of my team,” she said.

Receptionists, nurses, doctors and others have pulled together, and worked extra hours to keep operations going and prepare for a potential surge in COVID-19 cases in the hospital.

Dr. Romero has special admiration for the dedication of the ultrasound technicians. Their jobs require hands-on contact with patients during prenatal visits, conducting scans that can take a half-hour to an hour.

“The longer time they spend with people, the higher their risk of being exposed,” she said. “But they understand this has to be done. The information we get from the ultrasound is extremely valuable.”

She worries about what may lie ahead, as cases rise in the state, the country and the world.

She attended a recent webinar in which doctors from Italy and China spoke about their onslaught of cases. One day, a hospital had no patients in the intensive care unit with the virus. A day or two later, they needed 66 ICU beds.

The possibility that it could happen here haunts her. And it adds fuel to her pleas to family, friends and the community to practice social distancing.

“When we talk to you about not doing playdates or unnecessary shopping, that’s your little contribution to avoiding the spread of this disease,” she said.

In the back of her mind, Dr. Romero plots what to do if she is exposed to COVID-19.

How can she protect her husband, her children, and her 90-year-old grandmother, who lives with her? The disease can be especially deadly to the elderly.

“Do I come home, or do I stay somewhere else?” she wondered. “Do I send them away?

“It’s a bit overwhelming.”

So, what keeps her going?

“I took an oath. And I love what I do,” Dr. Romero said. “This is my responsibility, and this is what I was trained to do. I take care of patients. That is what I do every day.”

‘I understand the risks’

In a pandemic caused by a respiratory illness, respiratory therapists form an especially valuable vanguard of the front line.

They maintain patients on advanced life support, like mechanical ventilators.

They provide treatments for people who are coughing and having trouble breathing.

“We deliver aerosolized medications —that’s the most dangerous thing we could probably do,” Ann Bowman, RRT, said.

Yet Bowman seems unafraid of the task before her—the care and treatment of patients with COVID-19.

“This is my 36th year of employment with Spectrum Health. I’ve been around the block a few times,” she said. “I don’t think it’s really in my nature to be overly excited.

“I understand the risks, and I understand how to take care of myself and my patients.”

Bowman, who works in the cardiothoracic intensive care unit, said respiratory therapists always keep universal precautions at the forefront. They work with vulnerable patients—newborns, transplant recipients, those with cystic fibrosis—and are trained to take precautions against the transmission of viruses and bacteria.

In the COVID-19 era, she said, “We are continuing on with our disciplines and precautions that we always use. We always practice diligent hygiene.”

Having the right attitude matters, as well.

“We have to keep ourselves calm and create that calm, so we can help others be calm,” she said.

At home, she takes steps to protect her family. She and her husband do not see their four adult children. She urges everyone to wash hands, to take care of their health and to stay home.

“Don’t have friends over just because you can’t go out to the bar,” she said.

And she encourages people “to shop responsibly.”

“You don’t need a pallet of toilet paper,” she said. “You just need enough for the next couple of weeks. Leave some so other people can have toilet paper, too.”

Although Bowman anticipates the pandemic will mean long shifts at work, she is ready to do her part.

“That is totally when we want to be at the bedside,” she said. “We don’t go into health care because we want a 9-to-5 job.”

What it’s all about

Dr. Tsimis was a resident physician in 2012 when Hurricane Sandy struck New York and plunged lower Manhattan into darkness.

For days, he and his co-workers cared for patients in a hospital powered by a generator.

That is just part of his job, he says.

His mission.

COVID-19 may be new, but he and other health care providers draw on their skills and experiences gained treating patients through other crises.

A maternal fetal medicine specialist, Dr. Tsimis has been busy planning Spectrum Health procedures to screen pregnant patients, treat those with COVID-19 and protect others from the virus.

A commitment to put the patients’ needs above all else permeates the culture, he said. He sees it in the dedication of the environmental services crew that cleans and sanitizes, the medical providers who care for patients and the health system leadership.

“If we don’t show up, then no one else will. We are very cognizant of that,” he said.

“This is what medicine is all about. We signed up for it. We are ready for it.”

‘We are all here to support each other’

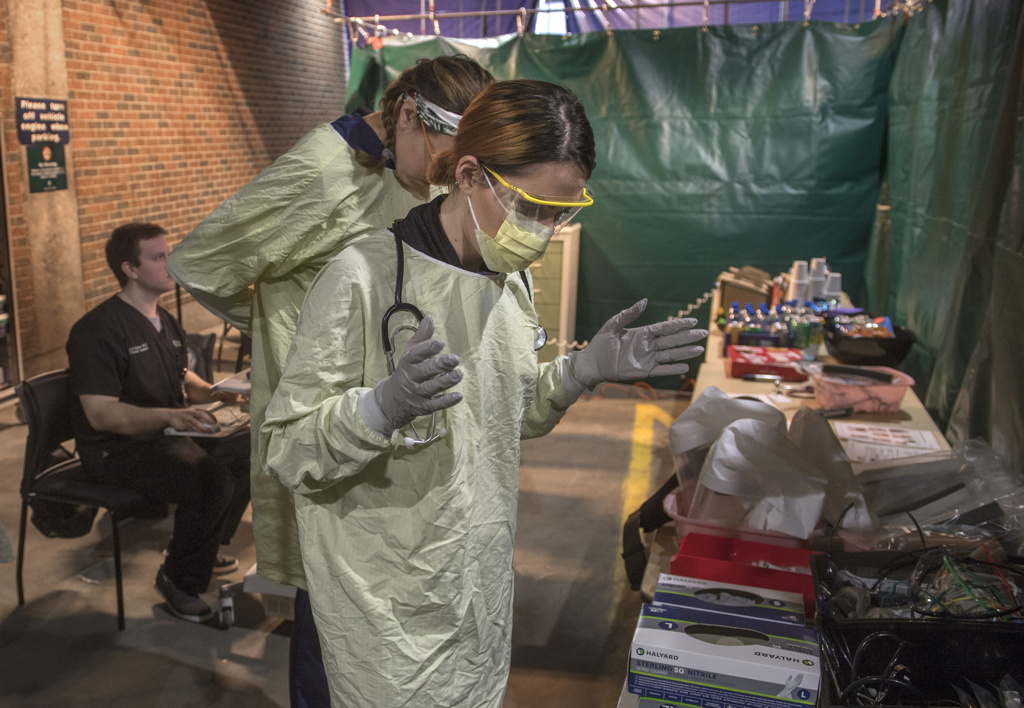

When COVID-19 arrived in the United States, Alex Robertson, RN, became anxious.

She worried about risks facing patients and health care workers. She worried about potential shortages of ventilators and other critical equipment.

“I was not sleeping good the first couple of days, knowing it’s not 1,000 miles away anymore,” said Robertson, a charge nurse in the Spectrum Health Fred and Lena Meijer Heart Center intensive care unit.

As staff worked to prepare for an influx of patients, she found inspiration in the resiliency of her fellow nurses.

“Nurses are great. We kind of adapt to everything,” she said. “We are all here to support each other as much as possible, and the rest of the staff, too.”

People drawn to the nursing profession tend to be interested in science and helping others—and that makes for a can-do attitude in a crisis.

“We have seen people step up pretty quickly,” she said.

Robertson and her husband, an emergency medicine specialist, follow steps to keep their home environment safe.

They sanitize their cell phones. They keep a separate laundry basket for their scrubs, which they wash promptly at the end of the day.

To cope with stress, Robertson takes care of herself mentally and physically.

She does yoga at home several times a week. She tries to eat healthy and sleep well.

“I might vent about problems with my husband,” she said. “And sometimes we turn it off and go outside for a walk.”

She urged others to listen to public health advice to stay home, wash their hands and take any steps they can to prevent the transmission of the virus.

“We are not making things up,” she said. “We are serious.”

Think about how much harder it would have been 20 years ago to be isolated at home, she added. In an era of FaceTime and other video chats, people have a lot of options to keep in touch.

“Hang on to your family members working in health care,” she said. “They are the ones who are working to protect us.”

‘We want to help’

Some health care workers have contracted COVID-19.

Some have died of it.

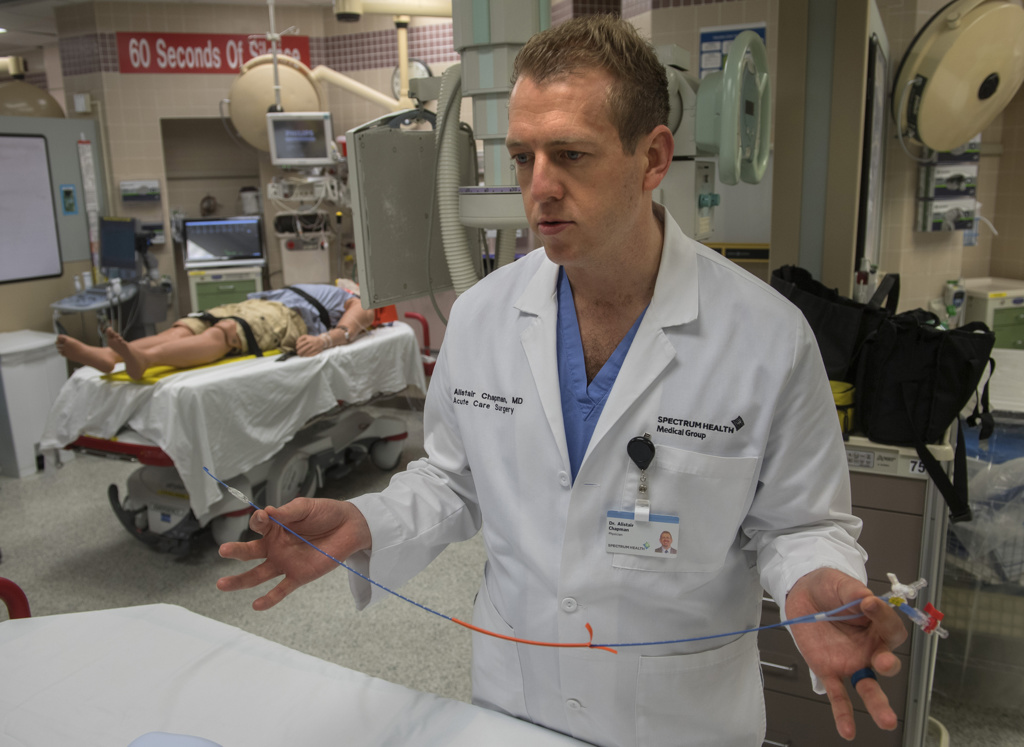

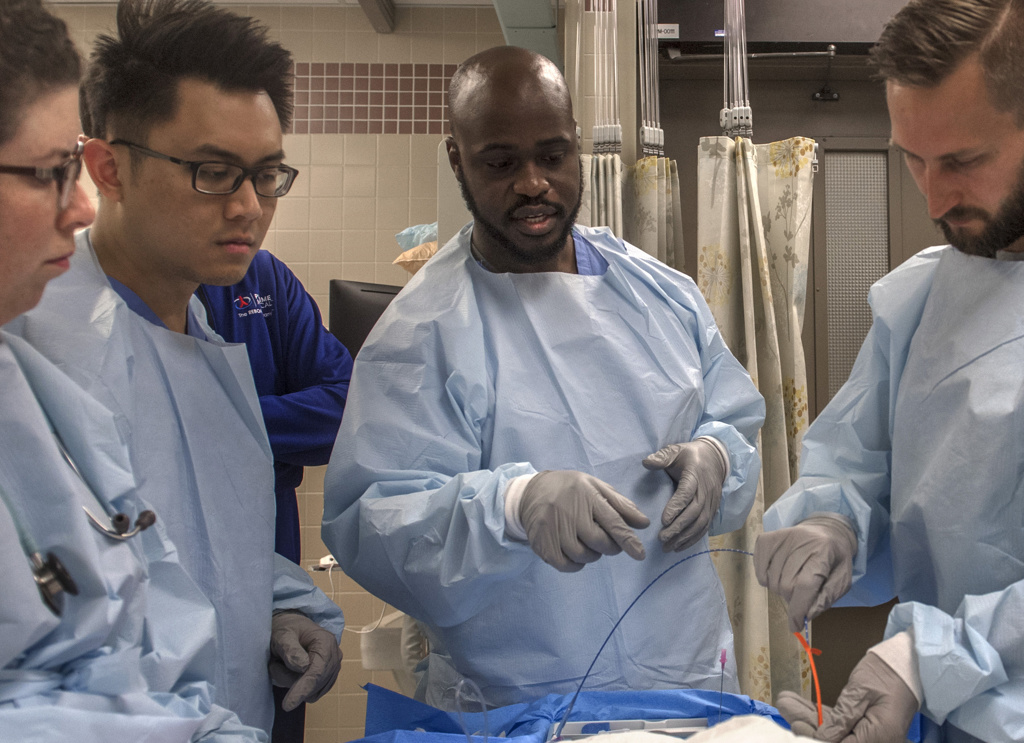

Hearing their stories brings home the risks that come with the job, say Spectrum Health acute care surgeons Charles Gibson, MD, and Alistair Chapman, MD.

“I’d be lying if I said people weren’t a little nervous about it,” Dr. Gibson said. “We know it is a risk to be exposed to these patients in this pandemic environment.”

But taking precautions against contagious illness is part of the job.

“Before any trauma patient comes in, we always don personal protection equipment,” Dr. Chapman said. “We assume that a patient at baseline is going to present with a potentially communicable disease.”

Their chief concern, as COVID-19 cases rise in Michigan, is how it will affect their ability to care for the severely injured and ill trauma patients.

On a recent weekend, Dr. Chapman performed two or three emergency surgeries each night. Trauma patients typically require intensive care, blood transfusions and specialized equipment such as ventilators.

In other areas, surges of COVID-19 patients have led to shortages of these critical resources.

“We worry about our ability to provide the highest levels of care for trauma patients if we have a huge influx of COVID-19 cases,” Dr. Chapman said.

“We have to ask our community to take this very seriously and continue to socially distance as long as this remains a threat.”

The surgeons take heart in the “all hands on deck” attitude throughout the health care team—the environmental services crew, nurses, respiratory therapists, technicians, physicians and other team members.

“What I’ve witnessed in the last several days is a sense of camaraderie,” Dr. Chapman said.

“Every time we ask something, it’s, ‘No question. Absolutely, we want to help,’” Dr. Gibson said.

That does not surprise him.

“Usually, one common thing among health care workers is that we all have a desire to help people in their time of need,” he said. “It takes a little bit of selflessness to have that in you.”

If there is one silver lining in the COVID-19 pandemic, it may be a downturn in the number of patients rushed to the hospital with traumatic injuries.

“Motor vehicles accidents and falls are the No. 1 and 2 reasons for admission,” Dr. Chapman said.

It’s too soon to tell, but the numbers of both appear to be dropping as society slows and people stay home.

Asked how non-medical folks can help in this crisis, the doctors advised staying home and following the state lockdown guidelines.

An occasional thank-you goes a long way, they added.

“It really means a lot to hear people say they appreciate the care we are providing,” Dr. Chapman said.

And do what you can to avoid needing a trip to the emergency department.

“Take your time. Let people over in traffic,” Dr. Gibson said. “Why be a trauma patient in the midst of this madness? Show just a little patience and a little love.

“Remember we are all in this together. We are all on team humanity and we are all trying to figure this out together.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

Also… thank all of the heroes behind the scenes! Environmental services, physical therapy, occupational therapy, respiratory therapy, lab technicians, Information Services, pharmacists, health aides/techs!! It takes a team!!!

It sure does! #TeamSpectrumHealth

You are so right. It does take a team. And the six people I interviewed all said that — and had high praise for their co-workers across all departments.

The dedication and selflessness of the front lines team members is inspiring – I also want to recognize the ATL team who is performing COVID-19 testing. Bringing up a laboratory test in such a short amount of time is no small feat and they are working tirelessly around the clock to get quality results out fast for our patients. The patient is and always has been their number one priority.

Many thanks to the ATL team! We’re lucky to have such an advanced lab available in our hospital.

Thank you for all you do for us.

Could you please tell me what is the best thing to use to wash clothes for this virus?

Thank you and please stay safe.

Hi Kaki. This virus appears to become inactivated with soap and water. I’ve personally been washing my clothes and my husband’s clothes (he’s in health care) with hot water and regular detergent; then whites with bleach, hot water and detergent. Here’s an informational post from the CDC on recommendations: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/cleaning-disinfection.html

Thank you to all the workers that are not able to perform their duties from home or an off site location! God Bless all of you and your loved one.

The words seem so inadequate for the depth they convey, thank you!

Thank you all so very much for what you are doing. Thank you also to Spectrum Health for supporting their employees. We need to all do our part to help control this! Please remind your family and friends to stay at home!

Drs. Chapman and Gibson were hero’s in Butterworth OR long before this virus, and will be long afterward. Praying for you and your families daily!

God bless you and keep you safe! Thank you all for your dedication and commitment.

Over the past few years I have had three stays at Spectrum Butterworth. It my hope that when this crisis ends the health care workers of Spectrum; doctors, nurses, PAs, NPs, assistants, lab techs, housekeepers and any others I didn’t list will be treated with the same dignity and respect that they showed me.

I am very appreciative of the good work you do.

To all the Spectrum Family,

Thank you for your brave& commitment to our community. Sending good vibes

Many, many prayers are being offered for each and every member of the Spectrum teams.

Thank you, Mary. I know your prayers are deeply appreciated.

Many thanks to all staff. I had surgery there a couple years ago and was very impressed with all of them. Heroes!!! You make me proud!💞💞