Jaclyn Folkema, 39, has always had a special heart.

She had been born blue, with a heart defect that sent blood flowing the wrong way. Doctors corrected it only through extensive surgery in her infancy.

Still, with minor lifestyle modifications—avoiding heavy exertion, for instance—she managed to grow up with few health problems.

But in college that all started to change.

Her weight began to creep up, a trend that continued through her 20s. After the birth of her daughter nine years ago, the creep turned into a gallop.

“I gained 100 pounds in the first two years after she was born,” said Folkema, of Hudsonville, Michigan.

She kept gaining, eventually topping out at 335 pounds in 2015. By then, the 5-foot-7 mom had also developed some of the byproducts of obesity, including high blood pressure, high cholesterol and severe sleep apnea.

Daily life began to look scary.

On a shopping trip to her local Meijer supermarket, she got so exhausted she had to stop every few feet.

“You don’t look so good,” a store manager told her.

Sweat poured off her face. She assured him she was fine.

“But it was horrible to have to stand there pretending to read a box of cereal because I couldn’t walk a few more steps without resting,” she said.

Soon after, she had an annual checkup with her cardiologist, now retired, at the Adult Congenital Heart Program at the Congenital Heart Center at Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital.

His alarm rivaled the grocery clerk’s.

“He told me, ‘You don’t have five more years to live. You’ve got to do something,’” Folkema said.

So when he suggested bariatric surgery, she agreed.

“In the past, I’d always thought about surgery as kind of an easy way out,” she said. “I kept thinking I should be able to control my eating on my own.”

But a more crushing thought persisted: If she didn’t do something, she might not live to see her daughter grow up.

She signed up for a seminar right away.

New living

Faced with a barrage of hurdles—insurance approvals, an iron deficiency and a heart condition—two years would pass before Folkema could undergo the operation.

Then it all came together in March 2017.

Jon Schram, MD, oversaw the operation in the bariatric surgery department at Spectrum Health.

Folkema quickly came to understand her earlier dismissal of bariatric surgery as an “easy way out” was far off the mark.

“It’s a very profound mental change,” she said. “You can’t eat the way you used to.”

For several weeks she ate only liquids, eventually graduating to pureed foods. From there she moved on to soft foods and, as the months went by, added tiny amounts of regular food.

To train herself to take small bites and chew each one 25 times, she dug out the baby spoon and plates her daughter had used.

Even now, 22 months and 172 pounds later, she attests: “I can only eat 4 ounces at a time.”

She consumes many small meals throughout the day and keeps her daily intake to 1,000 calories, helping her maintain a weight of 163 pounds. Included in that daily allotment is 60 to 80 grams of protein.

“Jaclyn is a shining example of a patient that set a goal, and then made the sacrifices necessary to reach it,” Dr. Schram said. “Her hard work and perseverance will assure her long-term success.”

“I have a different relationship with food now,” Folkema said.

And just as importantly, she’s enjoying teaching her daughter about this new and healthier style of eating and cooking.

“I’ve always been an emotional eater,” she said. “Now I can’t do that. So I have to find other ways to work through my feelings.”

Before the procedure she began seeing a counselor who specializes in bariatric patients. She continues to keep those appointments.

“It really helps to have that kind of a sounding board,” she said.

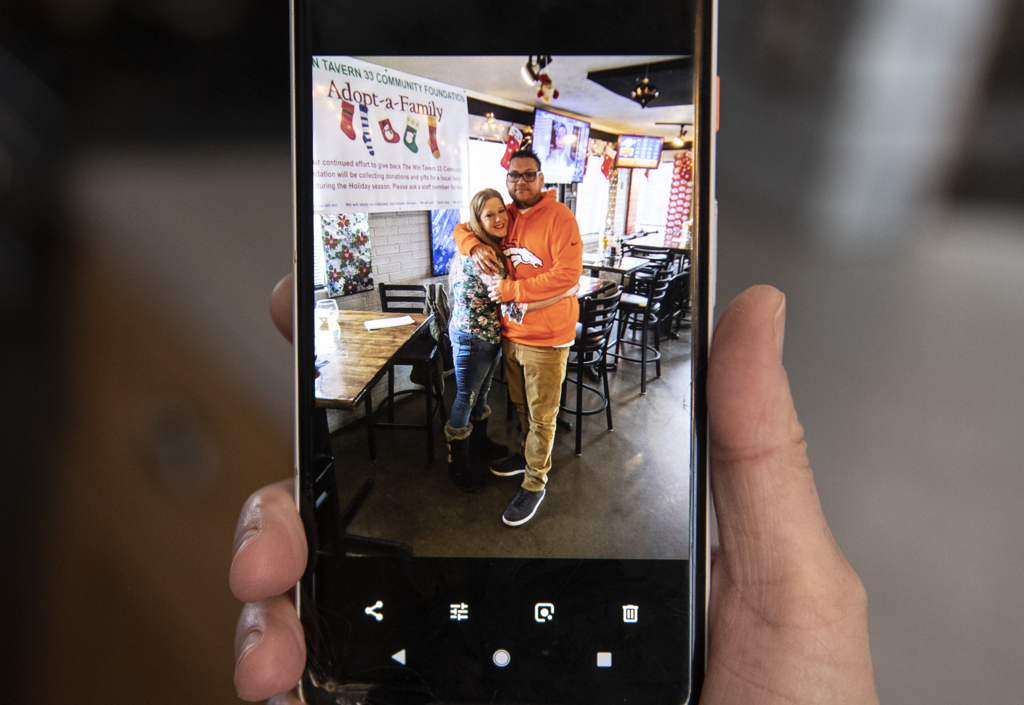

It’s all been worth it. The single mom has even started dating, striking up a friendship with a fellow bariatric patient in California she met through a Facebook group.

“This surgery has opened up all kinds of new possibilities,” she said.

The best part: She knows what it feels like to have her 9-year-old daughter wrap her arms around her. She knows what it feels like to run, play and swim together.

“For the first seven years of her life, I didn’t even own a bathing suit,” she said.

Her advice to those considering surgery: “Before anything else, talk to your friends and family. This is hard work—and having a support system in place is a big deal.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>