Grandpas shouldn’t get cancer.

They shouldn’t need chemotherapy. Or a stem cell transplant.

And they shouldn’t have to spend weeks in the hospital, separated from their grandkids.

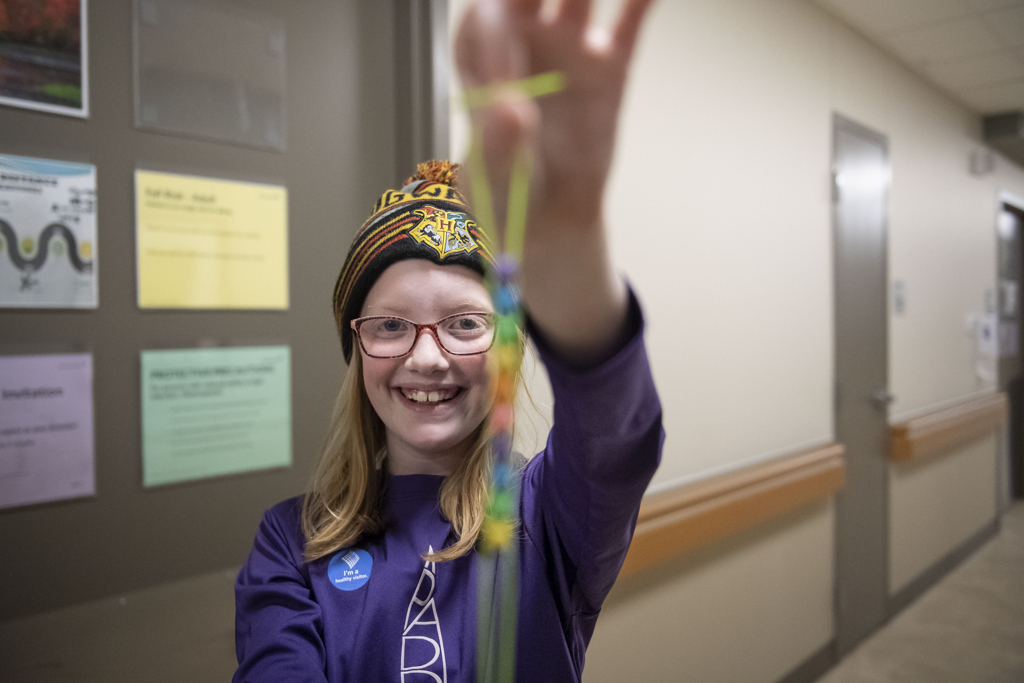

So when all that happened to 10-year-old Brynn Van Drie’s grandfather, it left her sad and aching for something to do, something big or small, to make things right.

Brynn came up with a special gift for her grandpa, Jerry Fondse, as he underwent a stem cell transplant under the care of Sami Brake, MD, and his team at Spectrum Health Butterworth Hospital.

She created a string of beads he could use to track the laps he walked every day during treatment.

She chose green string because the color represents lymphoma, the form of cancer her grandfather is battling.

On the string, she threaded a collection of pretty pastel beads. Three beads of each color.

Eighteen beads in all.

A good number, as it turned out.

She gave the chain to her grandpa on the day he arrived at the stem cell transplant unit.

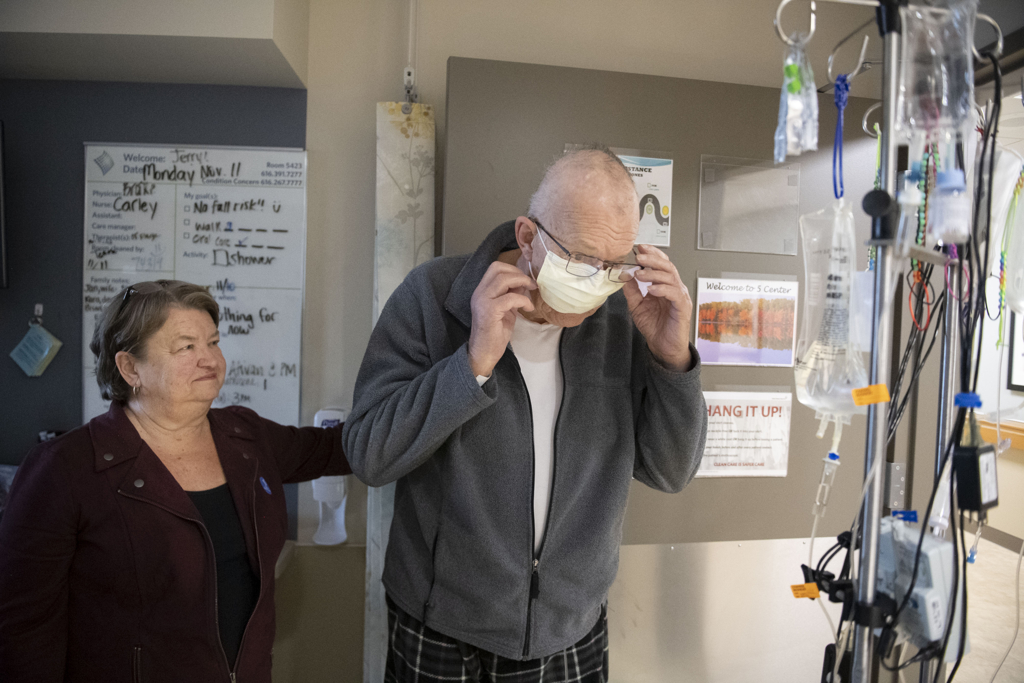

“The first day we got here, they had a paper on the door saying 18 laps equals 1 mile,” said Jerry’s wife, Jan. “We couldn’t believe that.”

In Jerry’s hospital room, the bead chain hung on his IV pole, his personal pastel rainbow of hope.

He used it on his daily walks, pulling down one bead with each lap.

And just the sight of it brought healing.

“It really comforts me,” he said. “When I look at it, it really brings me home, to the family.”

And to Brynn.

“I see this and I see all these colors—and that’s Brynn,” he said. “Everything is colorful with her.”

A reason to stop and chat

The walking beads became a conversation starter with other patients Jerry met on his daily strolls.

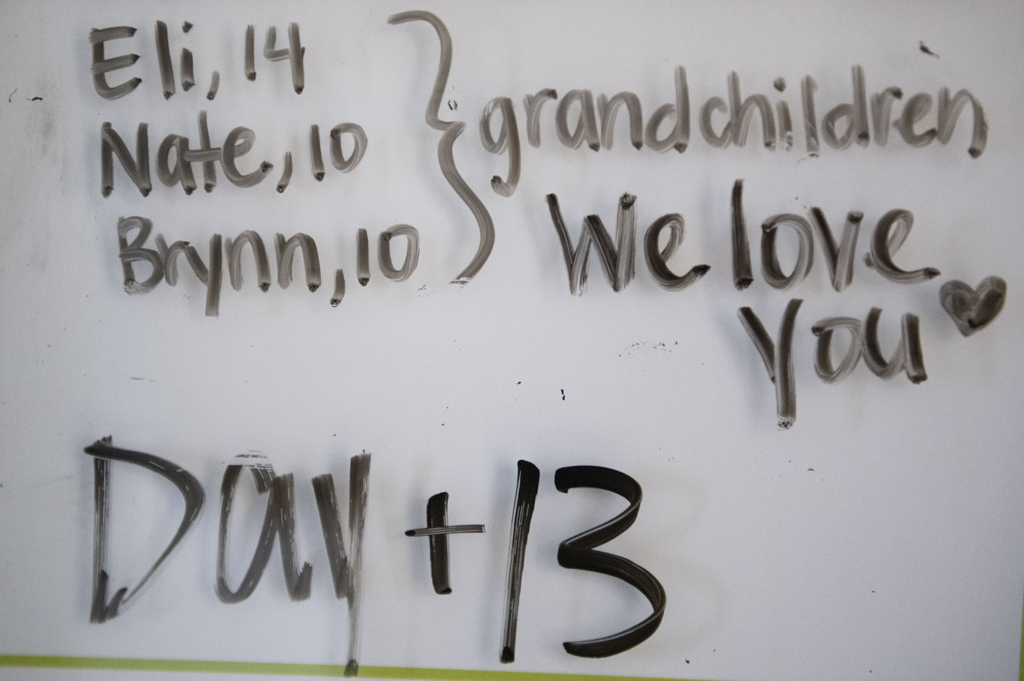

When she heard that, Brynn got to work making more chains. Her 14-year-old brother, Eli, and her twin brother, Nate, pitched in. Friends from church helped out.

Her grandparents handed out walking beads on their daily strolls.

Soon the colorful strands became a regular sight on the fifth floor of Butterworth Hospital, a playful touch of color swaying from IV poles.

They caught the attention of Bonita Neil, a physical therapy assistant. She heard from patients how much the beads motivated them. One woman said she managed to walk a mile one day, despite her fatigue, because she couldn’t wait to pull that last bead down the chain.

Neil tracked down the source, and was delighted to learn they came from Jerry’s granddaughter.

“This little girl is only 10 years old and she is making these beads for everybody,” she said. “I thought that was so cute and thoughtful. It’s such a huge act of kindness.”

The beads created a sense of community for patients undergoing a stem cell transplant, said Ashley Heiss, a physical therapy supervisor.

“It’s causing a lot of people to stop and say hello to each other, to talk about the beads and how far they have walked,” she said. “They encourage each other.”

The joy of grandkids

Jerry, a 72-year-old retired Calvin College English professor, learned in January he had a rare form of non-Hodgkin lymphoma called angioimmunoblastic T cell lymphoma.

“When I was diagnosed with cancer, Brynn took it really hard,” he said. “She climbed on my lap and cried and cuddled.”

It tugged on his heart—of all his fears about his diagnosis, he worried most about how it would affect his grandchildren.

“Somebody said having a grandchild is like falling in love all over again,” he said.

And for him and his wife, Jan, that meant falling in love three times—with the arrival of each of their daughter Kara’s three children.

After the birth of the twins, Brynn and Nate, the grandparents took turns helping out at night. They slept in the basement for four months so they could be ready to comfort a fussing child in the middle of the night.

“It was an amazing experience,” Jerry said.

Under the care of oncologist Latha Sree Polavaram, MD, and Dr. Brake, Jerry began chemotherapy treatments the day after his diagnosis. That consumed his life for the next five months. Complications required frequent trips to the hospital.

When his cancer went into remission in the summer, Jerry and Jan took the grandchildren to Yosemite National Park. Jerry grew up in California, and he wanted to show the kids the favorite spots from his childhood.

Knowing how important the trip was to Jerry, Dr. Brake and the stem cell transplant team made arrangements so Jerry could enjoy this last-minute trip before he started the stem cell collection for his transplant.

The key to recovery

On Oct. 21, Jerry arrived at Butterworth Hospital for his stem cell transplant.

His stem cells were collected and frozen after his trip to California. And then he underwent a week of high doses of four chemotherapy agents that wiped out his bone marrow and immune system.

On Oct. 28 and 29, he received his stem cells back, allowing his bone marrow to recover and make the blood cells his body needs.

With Jerry’s immune system suppressed, he had many restrictions to follow. He kept in touch with the grandkids by phone.

“When we FaceTimed, Brynn would say, ‘Did you give my beads to anybody today?’” Jan said.

Throughout his treatment, his medical caregivers encouraged Jerry to walk regularly. Research shows that those who stay active recover more quickly.

“They do so much better,” Dr. Brake said. “Their recovery is faster, and their discharge home is smoother.”

But oh, how hard it can be to take even a short stroll.

The chemo leaves patients exhausted, Dr. Brake explained. They have anemia, nausea and diarrhea—three things that make it difficult to stay active.

Despite all that, Jerry “did such a good job of walking,” he said. “It makes such a difference.”

And for that, Jerry gives the credit to the love symbolized in his walking beads.

“I think faith and family and a desire are huge,” he said. “You cannot underestimate the psychological component of healing.”

Taking a walk

On Nov. 11, three weeks after Jerry began treatment for his stem cell transplant, he had good news. His blood counts had rebounded enough to allow a visit from his grandchildren.

The kids gathered around. They reminisced about their trip to Yosemite and made plans for a return trip.

Eli talked about his trips to baseball stadiums with his grandpa.

Nate and Jerry talked about books and fishing.

And Brynn went for a walk with her grandpa, pushing the IV pole down the hall for him. At the end of the lap, she pulled down one bead on the chain to mark their progress.

Back in the room, they sat side by side.

“You’re the best granddaughter I have,” Jerry said, his arm around her shoulder.

It was well-worn comment, made many times over the years.

Brynn laughed and came back with her usual response: “But I’m the only one.”

Creating the bead chains helped the family as much as their grandpa, Kara said.

“It gives us something to do at home where we feel like we are being productive,” she said.

The family has a little bead workshop set up on the kitchen table. Kara hopes they can make bead chains for the kids in Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital, too.

Brynn loves to see how such little beads can have such a big impact—for her grandpa and many others, as well.

“It’s actually kind of nice to know that people are going to be able to leave sooner because they’re walking and doing stuff and not just sitting in their hospital room,” she said.

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

Brynn is a master at spreading joy. What a great story.

Brynn certainly has brought joy to her grandpa and many other patients receiving stem cell transplants. Thanks for reading.

The best solution to a most complicatedly challenging thing in life is usually the simplest. We call it ingenious. What a wonderfully encouraging story to all of us, Jerry, Kara, Brynn! God is answering our prayers for Jerry’s healing!

Yes Jerry, faith and family is what it’s all about. So happy for you that you are surrounded as you go through this difficult time.

This is phenomenal. Great work Brynn. I’d love to see employees support this as well. If there’s a donation plan, let me know.

Thank you so much Brynn for making the beads for the poles!!! My dad had a stem cell transplant this past fall and received the beads. He also was motivated by the beads to do more laps and get more miles in. He is a huge U of M fan and got blue and yellow beads and he thought that was great. I would also love to support this. Let me know if I can donate beads or money for this. Thank you for sharing this story.