Victoria Wyatt and her old heart had a reunion four weeks after her transplant.

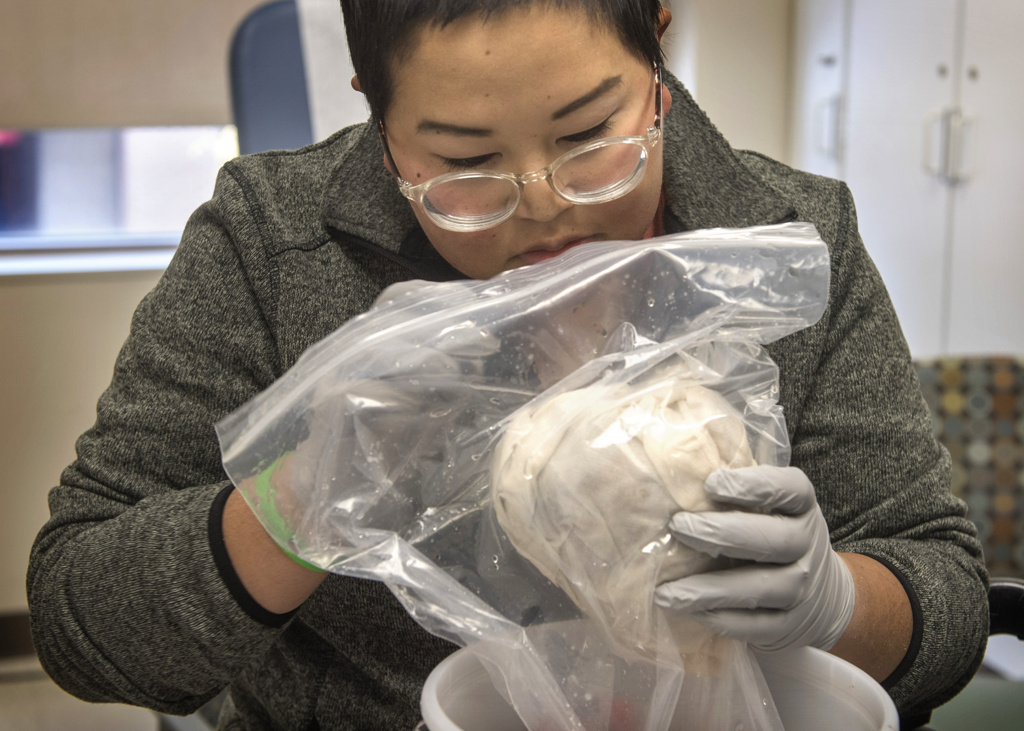

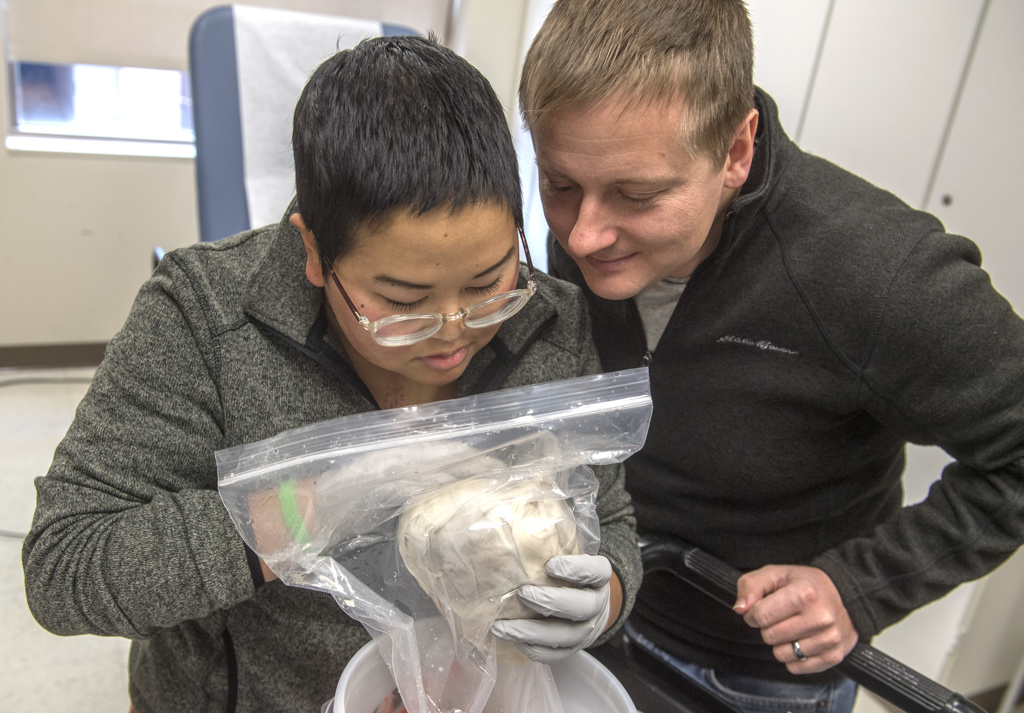

It wasn’t a graphic sight: The heart was wrapped in a white paper towel and encased in a plastic bag. But it was indeed the organ that had pumped in her body for the first 29 years of her life.

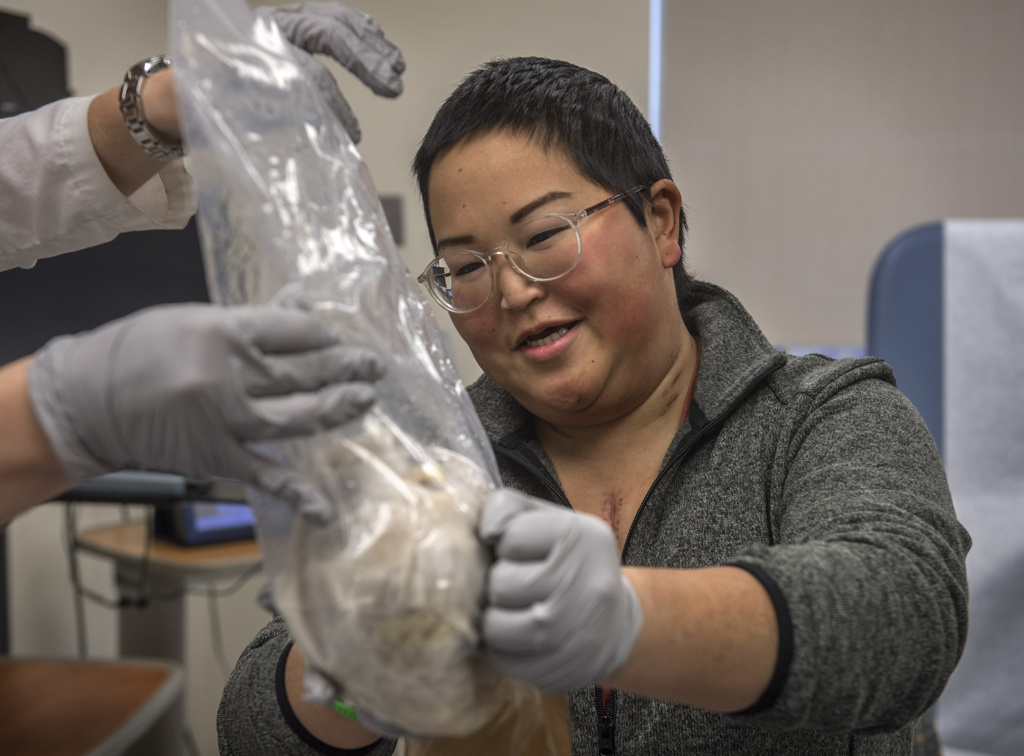

In a clinic room at the Spectrum Health Richard DeVos Heart and Lung Transplant Program, Victoria pulled on gray, latex gloves and lifted the plastic bag.

She gazed thoughtfully as she turned the heart back and forth, hefting it to feel its weight.

“It’s huge,” she said quietly. “It’s so heavy.”

Her husband, Jeff, took a picture of Victoria, smiling with her heart in her hands.

The heart, though enlarged and thickened by genetic heart disease, had not yet outlived its usefulness.

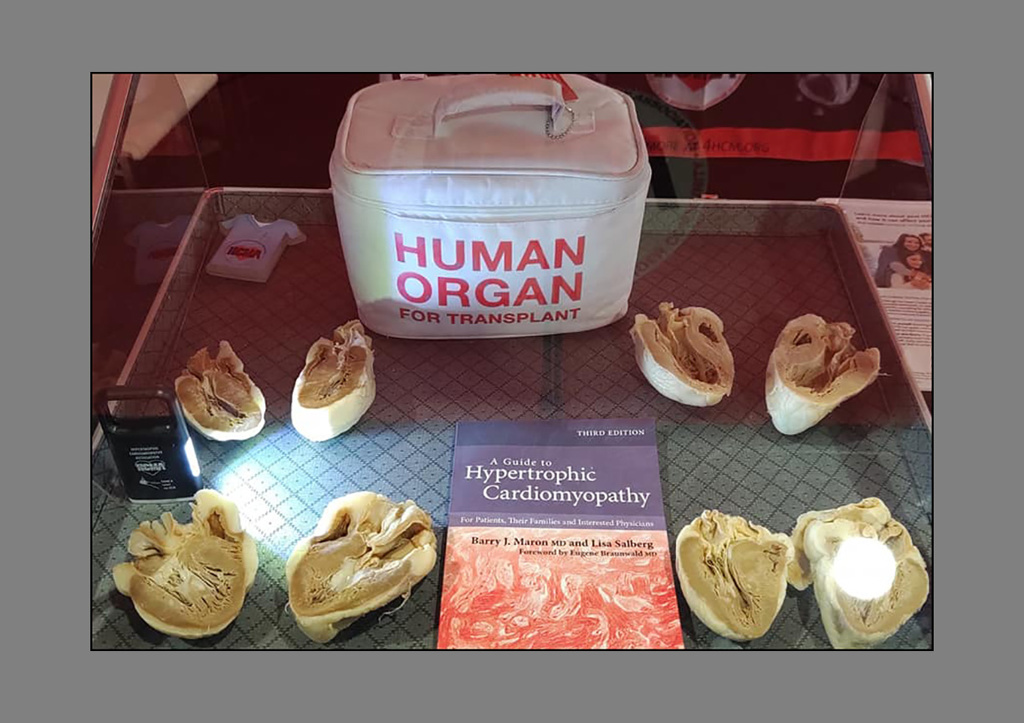

Victoria made arrangements to preserve the organ, creating a plastinated version that will help physicians learn about her heart condition, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, a genetic heart disease that causes abnormal thickening of the heart muscle.

“It’s going to be exciting to see my heart go toward something good and help other people understand this disease,” she said. “I can say at least it’s doing something productive in its second incarnation.”

Victoria, a 30-year-old woman from Grosse Pointe, Michigan, sees helping others as part of her mission after a transplant gave her a second chance at life.

A surprising diagnosis

When Victoria learned she had heart disease at age 14, the diagnosis interrupted her busy life as a high school freshman.

She felt unusually fatigued so her mom took her to the pediatrician’s office for a checkup. The doctor heard a heart murmur and referred her to a pediatric cardiologist.

After a day of tests, the specialist told Victoria and her mom the diagnosis: hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

The condition is best known in the general public as a cause of sudden, tragic deaths of young athletes, who suffer cardiac arrests.

But in reality it affects people of almost any age, causing a range of symptoms including shortness of breath, lightheadedness, heart pounding, or passing out. People may not even realize they have the condition because there may be no symptoms at first.

But it can cause a range of symptoms—and often people don’t realize they have the condition.

“I was actually pretty lucky,” Victoria said. “I know from talking to other people that a lot of them don’t get diagnosed that quickly.”

But as a young teen, she didn’t feel lucky. The doctor told her she had to quit the swim team.

“I loved swimming,” she said. “It was right in the middle of the season.”

Through her teens, she became winded easily during physical activities. But she continued practicing martial arts.

“I probably pushed myself a lot further than the doctors would have liked,” she admitted.

In her early 20s, she often felt out of breath. But she chalked it up to a lack of exercise and long days on the job.

At 25, she saw a local cardiologist, who ran a series of tests. The results shocked Victoria.

“He said it’s gotten so much worse. He said I was in heart failure,” she said.

She began taking several medications. And she underwent septal myectomy—surgery to remove excess muscle from the septum of the heart. She felt better afterward—but the improvement lasted only about a month.

That’s when Victoria turned to the Spectrum Health Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Program, one of two Centers of Excellence in Michigan recognized by the Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Association.

The program provides a comprehensive approach to diagnosis and treatment. Patients receive care from a multidisciplinary team that includes cardiologists, surgeons, nurses and genetic specialists.

“It’s the most common type of genetic heart disease. But it’s uncommon enough that they recognize it is best taken care of at a place where we see a large number of cases,” said Victoria’s cardiologist, David Fermin, MD.

Tests showed Victoria suffered from a “burned-out form of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy,” Dr. Fermin said.

“That meant her heart was basically just turning into a big scar. It’s called fibrosis—the heart muscle becomes stiffer and stiffer as it is replaced by fibrous tissue.”

Without additional medication or surgery available to reverse her condition, a heart transplant became her only option.

Waiting for a new heart

At that point, Victoria had become so weakened she struggled to walk across a room and always needed a cane for support.

In October 2017, Victoria began to receive an intravenous drug, milrinone, which relaxes blood vessels to help them dilate. It provides short-term help for people with life-threatening heart failure.

For the next two years, Victoria remained hooked up to the IV medication, carrying it in a fanny pack everywhere she went.

“It was remarkable how much of a difference it made,” she said. “I was able to keep working for about another year. I was able to leave the house and do things on my own.”

However, the effects of the IV milrinone gradually diminished, and it became more difficult to remain active and attain a healthy weight, which is one criteria for heart transplant listing.

She underwent bariatric surgery. Because the procedure is not commonly an option for end-stage heart failure patients due to the risk, this required significant coordination between Victoria’s Spectrum Health cardiology and bariatric surgery teams. She succeeded in losing enough weight to be listed for a transplant in July 2019.

In August, with her heart failure progressing, she stayed in a room at Spectrum Health Fred and Lena Meijer Heart Center. She remained there 59 days, waiting and wondering if a donor heart would become available in time.

One October night, she received a call from a transplant coordinator saying: “We have a heart.”

“I couldn’t breathe,” Victoria said. “You’re almost thinking this is never going to happen. It was surreal to get that call.”

In the operating room awaiting surgery, Victoria thought about two close friends who died from complications after transplants.

“They were such strong people who fought this so long,” she said. “I have to do as much living as I can in memory of them.”

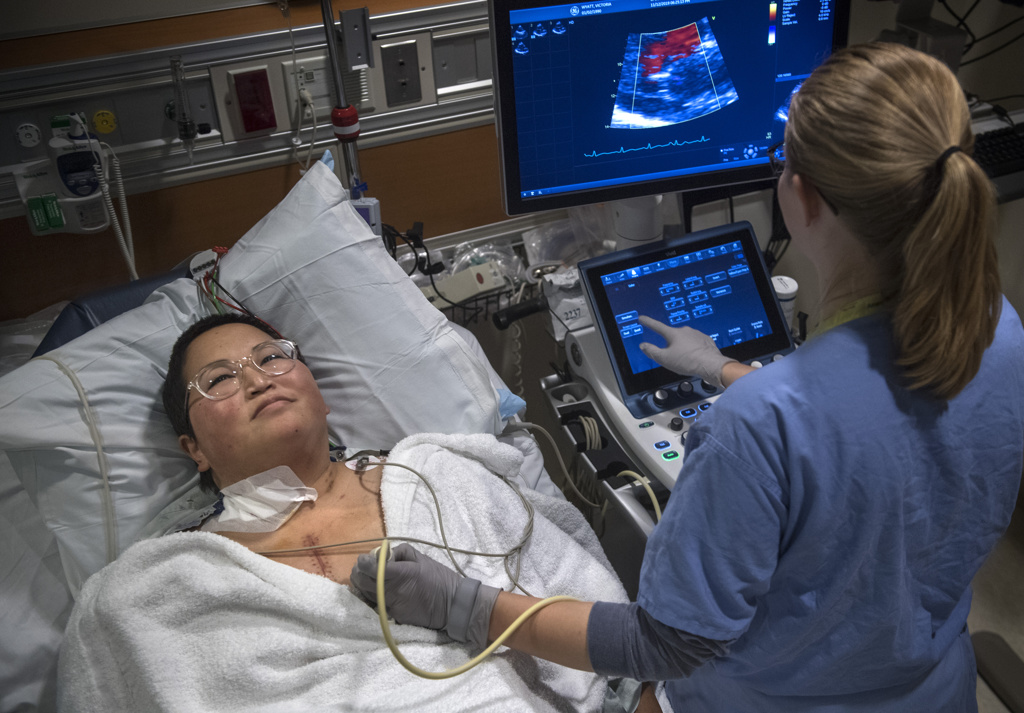

She recalls waking up the next day and recognizing that a new heart beat in her chest. She no longer felt the heart palpitations that had been with her constantly.

“Even now I have to think about it—that this is a different heart,” she said. “It’s so much more compliant. It does what it’s supposed to do. My old heart would act up so much, it was always in the front of my mind.”

Preserving the old heart

To raise awareness about the disease, Victoria became active in the Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy Association, serving as a moderator for its Facebook group. She talks with newly diagnosed patients about her experience with the disease.

One thing she stresses: Not everyone will have such a severe form of the disease that they require a transplant.

“They say 1 in 200 to 300 people are genetic carriers for the disease,” she said. “Probably out of all those people who have it, only 3-5% need a transplant.”

Dr. Fermin adds: “Some people have the misconception that it only happens to young athletes, but it can affect anybody, at any age. That’s why it’s very important for people to know their family history.”

Victoria also decided to follow the example of other patients, and have her heart preserved so it could be used to educate others.

“I’ve seen other specimens already,” she said. “You just see how this one disease looks different from person to person. No two patients will ever be exactly the same.”

Plastination of her heart will take a year and involve efforts by specialists in Texas and Ohio. A cardiac pathologist will first section the heart. Then it will be dehydrated and rehydrated with plastic.

“That’s exciting for me—to actually see the heart and the scarring and the thickness,” she said.

Dr. Fermin saw plastinated hearts at a conference recently and agreed they are valuable teaching tools.

“There’s no good replacement for actually seeing what a real heart with this disease looks like,” he said.

Getting her life back

As she recovers from surgery, Victoria and her husband, Jeff, look ahead to the opportunities that come with her new heart—and new health.

The couple has been together 11 years, and Jeff watched as heart failure took its toll on his independent, strong-willed wife.

“It’s exciting seeing her be able to get her life back,” he said. “Her being sick and not able to do things became kind of normal for us. That normal is going to be changing, which we are excited about.”

Victoria’s mission to help others with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy does not surprise him.

“That’s a staple of who she is,” he said. “She likes thinking about other people first.”

Victoria feels a keen sense of gratitude and responsibility for the gift of organ donation.

“Because I got a heart, somebody else was not able to get a heart and is still waiting,” she said.

“And to think of a family whose loved one has passed away being asked, ‘Do you want to donate those organs?’ I can’t imagine what that would be like. For them to say yes, that’s a huge deal.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

What a great story, well written! Victoria’s spirit shines through.

Whoa! What an incredible experience. So fascinating.

Victoria plans to follow her heart through as it goes through the steps to preserve it — through plastination. It will be amazing to see it when the process is complete.

Amazing story. Thank you for sharing. The picture gallery itself was incredible.

Agree! As a photo journalist, Chris Clark does such a great job telling a story visually.

She is an amazing women and her husband is an amazing person himself, I enjoyed being able to care for her and get to know her and her husband while she waited and was so excited i worked the night she got the call.