When a baby is born, a parent’s heart overflows with love.

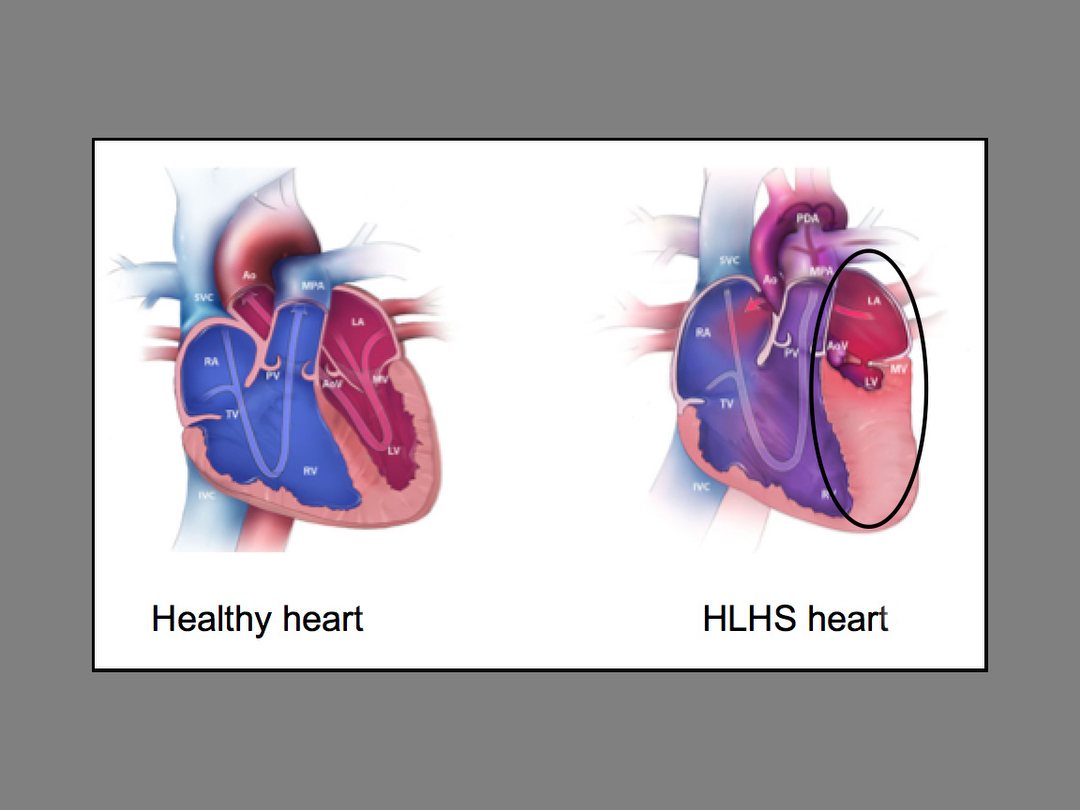

But warm and fuzzy emotions quickly turn to terror and panic for parents whose newborns suffer from complex congenital heart disease, also known as hypoplastic left heart syndrome.

Often, these babies require open-heart surgery within the first two to three days of their lives, a procedure that is both invasive and dangerous.

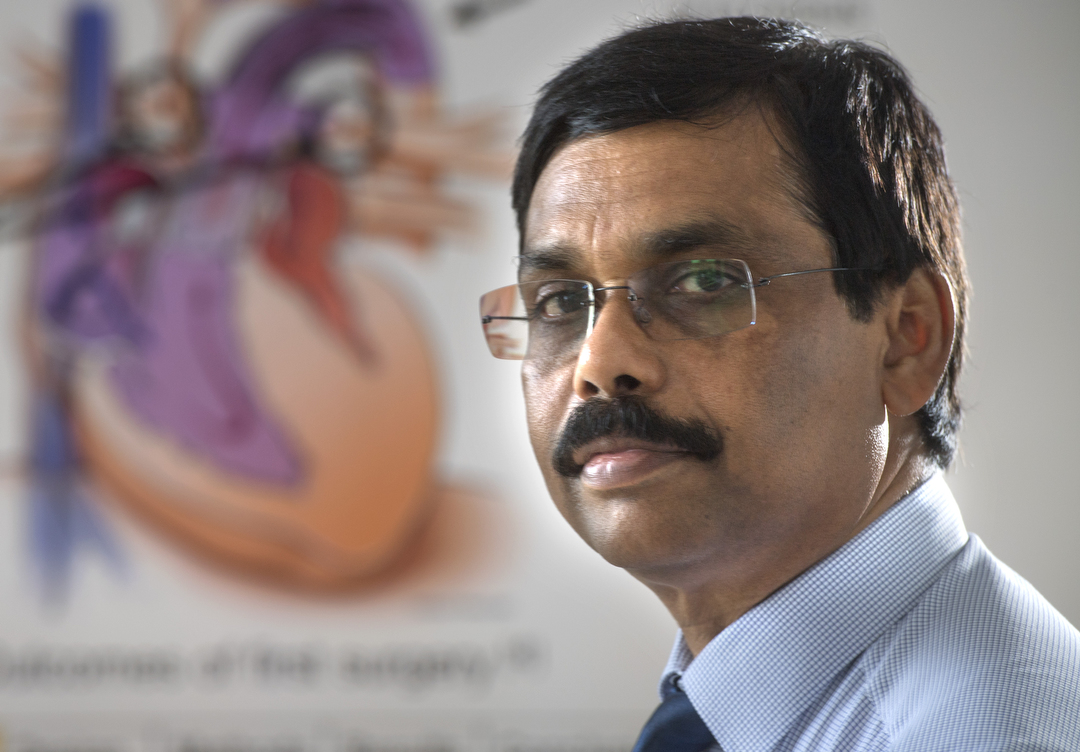

Joseph Vettukattil, MD, a pediatric cardiologist at Spectrum Health Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital, came up with the proposal for a device that could change all that. With the help of Spectrum Health Innovations and engineering staff and students from Michigan Technological University, the device may become a reality.

About a year ago, Dr. Vettukattil approached the Innovations team with the idea for a new stent device for babies who suffer from hypoplastic left heart syndrome.

“The management of HLHS is a difficult problem with high mortality in newborns, especially if they are of low birth weight,” Dr. Vettukattil said.

Current open-heart surgical inventions to correct the problem also carry a high mortality rate.

An alternative to open heart surgery is a procedure called a hybrid intervention. A surgeon opens the chest and puts a band on the pulmonary artery branches and the interventional cardiologist puts a stent from the pulmonary artery to maintain blood flow to the body.

Dr. Vettukattil’s new device, which would be designed to avoid the need for immediate surgery, could, if approved by the FDA, be a huge breakthrough in pediatric heart surgeries of this type.

Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome accounts for 2 to 3 percent of all congenital heart defects. Approximately two to three of every 10,000 live births in the United States suffer from this condition.

According to Dr. Vettukattil, the stent is intended to protect the lung from pressure damage and maintain blood flow to the body. Also, if the stent is approved by the FDA for patient care, once implanted, it could avoid the need for surgeons to open the patient’s chest and complete what is known as a keyhole procedure.

Award-winning design

Teaming up with staff and students from Michigan Technological University, the device is getting closer to testing.

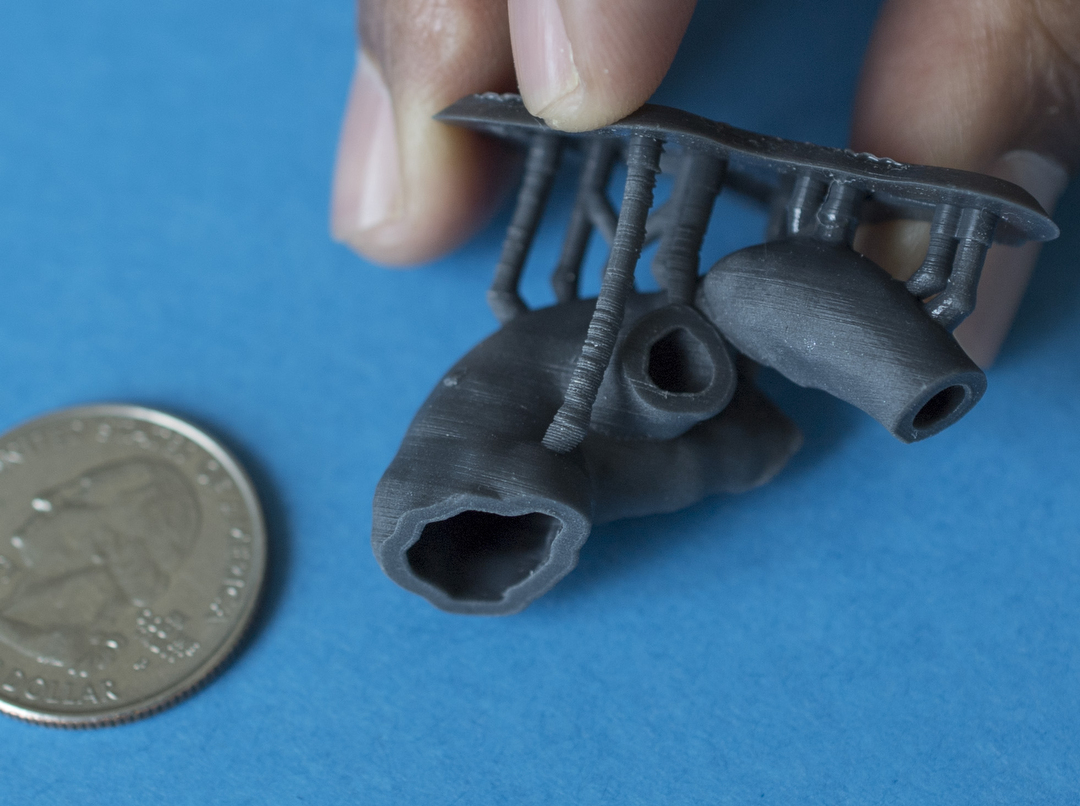

The device, formally known as a transcatheter single ventricle device, is designed to be deployed in the baby’s heart via a catheter.

It is intended to remove the need for the first stage of surgery, improve recovery time and potentially decrease complications from future surgeries because of less scar tissue buildup.

Under current methods, a baby’s 25-day hospital stay after the first surgery costs more than $200,000. Many babies stay in the hospital for six months to a year after the first surgery.

Using a 3-D printed heart model of an actual patient, Michigan Tech biomedical engineering students worked closely with Dr. Vettukattil and their professors to develop a prototype for the device.

The device has already won several awards at the school’s 2017 Design Expo.

This coming school year, students plan to work on figuring out the best way to decrease the flow to the pulmonary arteries.

Eventually, the hope is the device will be ready for animal studies, followed by human clinical trials.

Brent Mulder, PhD, senior director of Spectrum Health Innovations, said the final product could take up to 10 years to come to fruition.

“There are a lot of things that can happen along the entire journey, but we’ve been really happy with the path it’s taken so far,” Mulder said. “Getting a device to market takes years and years. This is a highly complex device.”

Mulder said a typical medical device of this type takes eight to 10 years to take it from idea to implementation.

“It’s still in the very early stages,” he said.

But even in the work-through stages, it’s a win-win for Spectrum Health staff and Michigan Tech students, according to Mulder.

“It’s a great experience for the students because they get to engage with a hospital system like Spectrum Health and they get to speak with Dr. Vettukattil and his clinical nurse on a regular basis to get feedback,” Mulder said. “Our clinicians get to see things from the engineering side. There are things they look at from a totally different perspective.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

Yes! Very powerful & uplifting for ALL involved 👍😍🎉🤘

Indeed it is, Jim! Thank you for your kind comment, and for being a Health Beat reader!