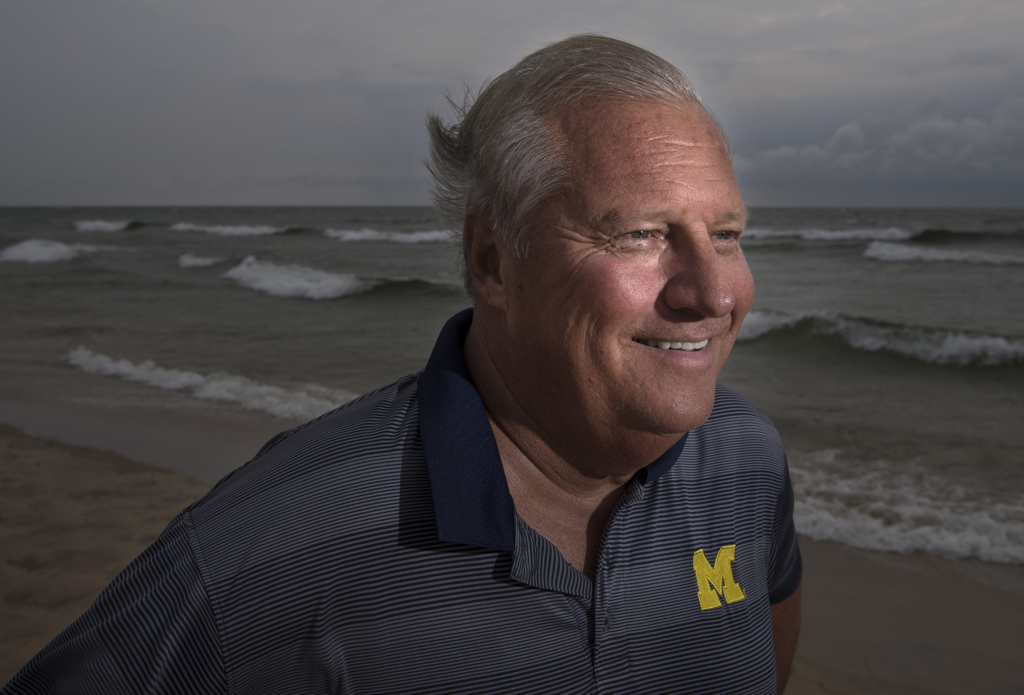

Walking the strand of a Dominican Republic beach, awash from the Caribbean Sea to the Atlantic Ocean, Terry Fewless’ thoughts were not on the trucking company he grew to $50 million a year in sales.

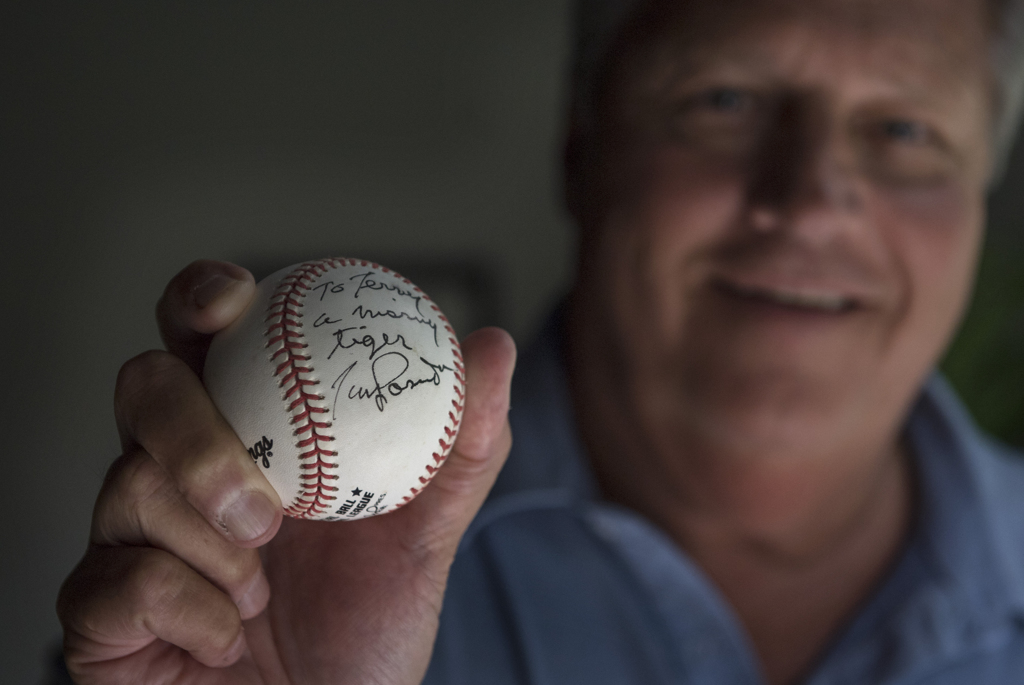

They were not about his youthful brushes with baseball greats, including the post-1968 World Series Tigers.

They were not about the 300-stitch leg injury that ended any hope of the Big Leagues.

At this moment in 2007, Fewless’ thoughts were about his breath, or lack of it.

“When I walked the beach, or walked fast, I would get a little bit of pressure in my chest,” said Fewless, now 64. “It was only when I exerted myself, like on sand. It’s when I put my heart under stress.”

That was his first day of vacation. Fewless backed off activities and promised to see a doctor immediately after the 2,000-mile trip home from Punta Cana.

“At 11 a.m. Monday, I walked into Spectrum,” he recalled. “I told the emergency room I needed a stent. I already knew what was happening. I said, ‘I know you’re going to find a blockage.’”

They found two. Doctors placed a stent to open a partial blockage in his left circumflex artery but also found his right coronary artery to be completely blocked. Doctors prescribed medication to try to treat any symptoms such as chest pain. It was his best option at the time.

For a few years, he did well. Then he developed progressive, intermittent chest pain that occurred with activity.

“I was miserable,” Fewless said. “I couldn’t run. I just couldn’t walk. It bothered me so much. I could have done that for many, many years. My life was terrible. I would always have discomfort.”

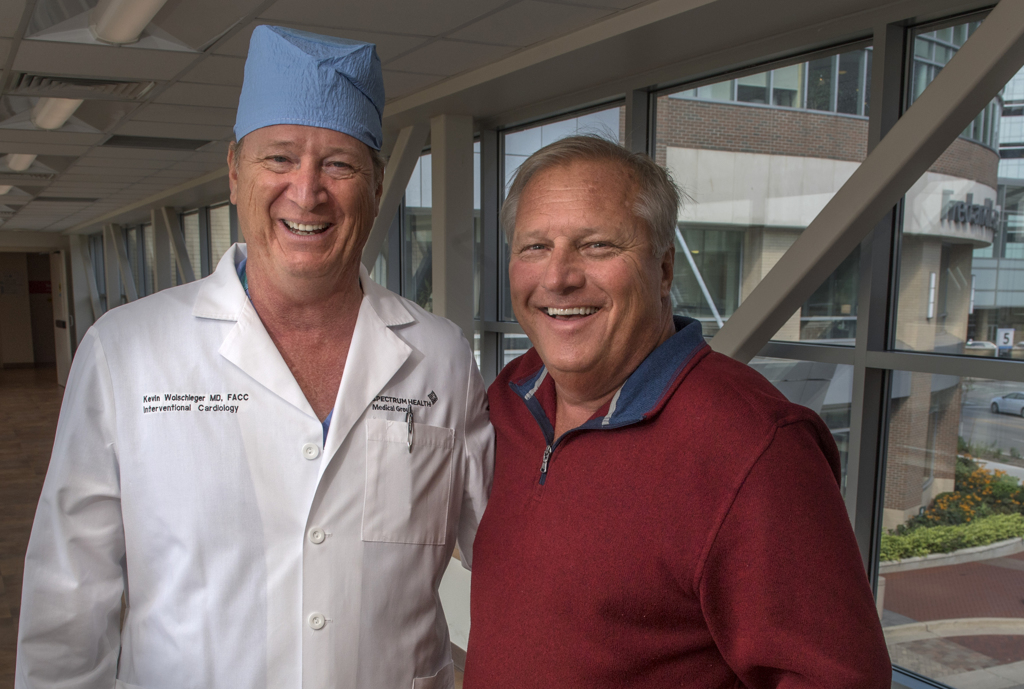

A second surgery placed a second stent. Then, in March 2014, Fewless walked into the Spectrum Health chronic total occlusion clinic.

Just a year earlier, Spectrum Health Medical Group cardiologist Kevin Wolschleger, MD, and fellow cardiologist David Wohns, MD, had trained on new equipment and techniques to treat chronic total occlusions.

A wire, just .014 inches in diameter, is the key. A chronically occluded artery is hard, calcified plaque. A wire must be placed past this blockage to guide the balloon and stents needed to open the artery.

Dr. Wolschleger guided the wire from Fewless’ femoral artery in his groin to his heart, opening the blockage and reinforcing it with a stent.

Treating CTOs have been a final frontier in coronary artery disease, the physician said. Previous techniques and wires were insufficient to penetrate totally blocked arteries, Dr. Wolschleger said, noting not everyone is a candidate for bypasses (especially if only one artery is closed).

About 75 to 100 such operations are now done annually at Spectrum Health; 80 percent are successful on the first try, more than 90 percent on the second, he said.

Baseball dreamer turned businessman

Fewless graduated from Wyoming Rogers High School and caught the eyes of a Detroit Tigers scout at a prep championship tournament in 1973.

The high school shortstop was asked to tryout in June with the team. A number of the ’68 World Series champs remained Bengals at that time—Mickey Lolich, Bill Freehan, Willie Horton. Managing legend Billy Martin wore the Old English “D.”

Fewless learned what it takes to play in the Big Leagues when he ran sprints. He says he got a good look at another tryout, from behind. Ron LeFlore could not outrun cops—he was serving time for armed robbery—but had been given a one-day pass to tryout as well.

“I got smoked,” Fewless said. “I got dirt in my face.”

LeFlore, a future Tiger All-Star, would go on to lead both the American and National leagues in stolen bases.

“Looking at Major League players today, they are so much better than I was,” Fewless said.

After a left knee-to-foot workplace injury with a fork lift—300 stitches—Fewless’ Major League hopes were over.

He began his trucking career in the mail room of a Toledo transportation logistics company in 1976. He left as a vice president in 1992.

In Lansing, Fewless founded Total Quality Inc., specializing in transporting cold chain, temperature-controlled products such as pharmaceuticals.

He sold the company in 2013 and he and his wife, Amy, moved to Big Rapids. He founded a new company two years later with his sons Kristopher, 43, and Nathan, 41, to spend more time with them.

Quality Life Science Logistics and Transportation in Spring Lake handles more than 200 semi-truck loads a week for the pharmaceutical and food industries.

A modern malady

Hardening of the arteries, or atherosclerosis, is often thought to be a modern malady. Think of drive-through cheeseburgers, French fries and other processed foods heavy in saturated and trans fats. Smoking, alcohol and lack of exercise are contributors.

But studies have also documented plaque build-up in 4,000-year-old mummies, according to an article in The Lancet medical journal.

“We found that heart disease is a serial killer that has been stalking mankind for thousands of years,” the study’s co-author wrote.

In a recent Spectrum Health video, Dr. Wolschleger recounts “patients who have lived with chest pain for years and years. … And when you do take someone that is so sick and you help them, they’re so appreciative. That’s what gets you out of the bed in the morning. That’s what makes you keep coming back, for things like that.

“One gentleman told me he left here, he went down to Florida. He couldn’t walk before we did the procedure. He couldn’t walk a block without getting chest pain. (Later, after treatment,) he went for a walk on the beach with his wife, walked 2 miles, came back, felt so well he walked another 2 miles by himself, just because he could do it.”

That gentleman is Fewless. Today, he continues to feel well with no chest pain or shortness of breath, four years after his chronic total occlusion procedure.

“My artery looked like a hot dog and the whole hot dog was filled with blood going to my heart,” Fewless said. “My life today from having that done is unreal. I can run. I can walk. I can do anything, I have zero discomfort. It’s just amazing what I can do.

“I couldn’t even tell them how good I felt without crying,” he added. “That’s how powerful it was, to let me have a life I always wanted.”

That includes more walks with Amy, his wife of 20 years.

“She was with me every step of the way,” he says, including all those years ago, on that Caribbean beach where he struggled to pull a breath.

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

Great story!

Thanks, Barb!

Dr. Wolschleger is the best! He performed a successful procedure on my husband last December to unblock an artery and he is back to riding his bicycle and exercising again. I am glad Mr. Fewless had the same results.