In 2020, the Hitts family gathered around the bonfire to enjoy the Fourth of July holiday.

Everyone had smiles—except Paul Hitts, then 58.

“My son was having this celebration of the holiday, but I couldn’t breathe,” Hitts said. “The smoke was following me wherever I would go and I couldn’t get air.”

Hitts reluctantly excused himself from the party and headed to his home in White Cloud, feeling queasy.

During the night, feeling still worse, Hitts rose from bed and went to the bathroom.

He struggled for air.

“I looked down at my hands and feet and they were turning blue,” he said. “I knew I was about to pass out.”

He awoke hours later, still in the bathroom, still winded. He tried to call out to his wife, Laurie, but his voice came out a whisper.

He simply couldn’t get enough air into his lungs to make much of a sound.

“I reached for something in the bathroom to throw at the door and make a noise,” Hitts recalled.

It worked. His wife woke up and opened the door, only to find her husband about to black out once again.

As he slipped in and out of consciousness, an ambulance arrived and took him to the emergency department at Spectrum Health Gerber Memorial in Fremont, Michigan. He would spend the next three-and-a-half days in a chemically-induced coma.

The culprit? Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

‘Spiraling out of control’

In January 2017, doctors had diagnosed Hitts with COPD, or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

For 40 years, he had been a heavy smoker, two to three packs a day. He had picked up the bad habit during his time in the Army.

About 16 million Americans have COPD and probably millions more suffer from it undiagnosed, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

COPD includes emphysema and chronic bronchitis, conditions that make it difficult to breathe. The most frequent cause of COPD is tobacco smoke, but air pollution and genetics are also contributing factors.

Symptoms include shortness of breath, wheezing, coughing and excessive phlegm or sputum.

Doctors diagnose the disease by using a breathing test called spirometry.

“My COPD was spiraling out of control,” Hitts said. “I love my job, working at a gravel pit on a construction site. But it’s physical work and I was getting tired and winded faster and faster.”

Some days, he’d have to pull his truck off the road so he could take a nap.

“I was too tired to make the drive home,” he said. “Just walking 20 feet was becoming too much. I ended up having to quit my job.”

The disease didn’t just affect his work— it also inhibited his ability to enjoy family time with his 16 grandchildren. It became too much to bear.

Hope restored

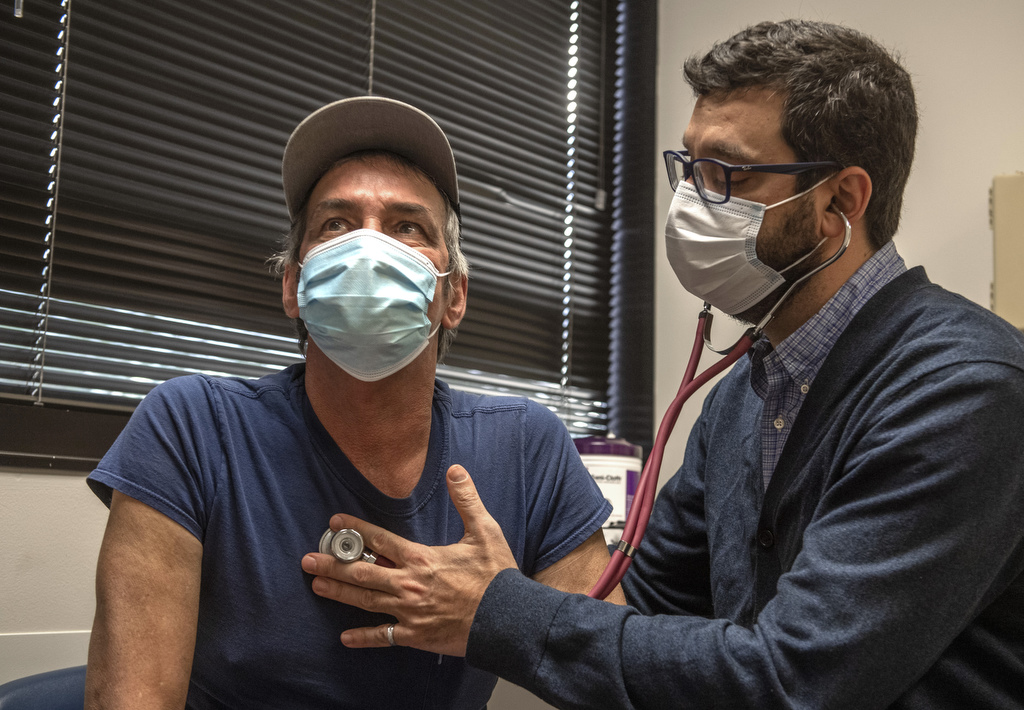

Hitts soon met with Gustavo Cumbo-Nacheli, MD, an interventional pulmonologist and pulmonary medicine physician at Spectrum Health.

“By the time Paul came to me late in 2020, his time was running out,” Dr. Cumbo-Nacheli said. “He was too ill to tolerate surgery. But he had done extensive research on COPD. And I had a non-surgical option to offer him.”

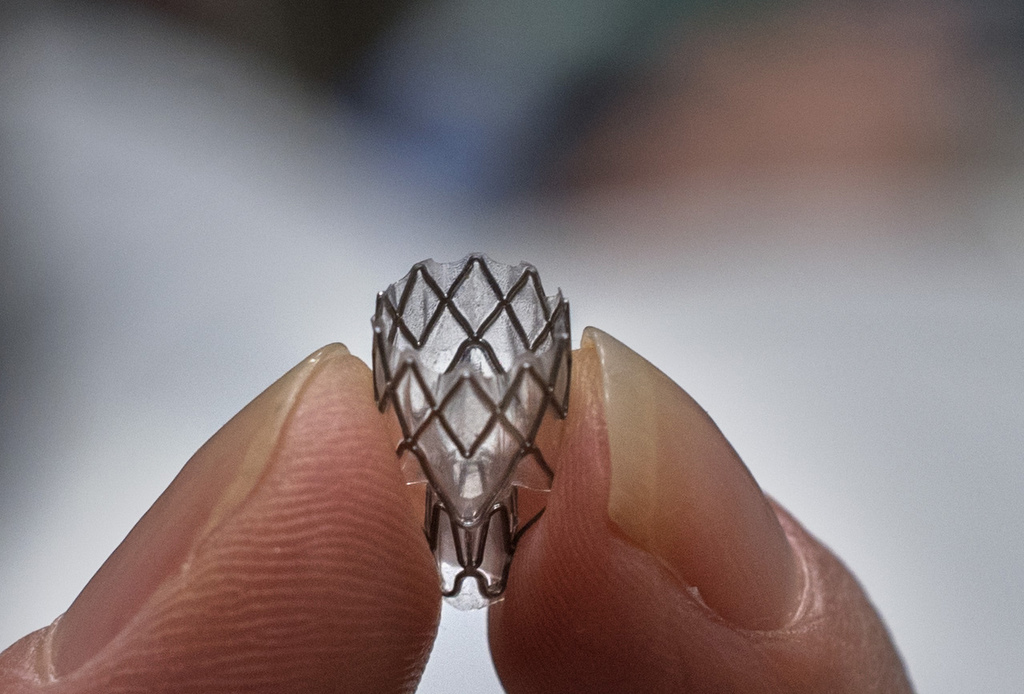

The Zephyr endobronchial valve is a minimally invasive treatment.

Doctors use a bronchoscope to place tiny, one-way valves in the patient’s airways. The valve releases trapped air and allows the lungs to function better.

“The Zephyr valve creates real estate for the lungs,” Dr. Cumbo-Nacheli said. “We use software that identifies the most damaged area of the lung.

“We place a one-way valve in the air pipe and that air then gets funneled to a healthier part of the lung,” he said. “We do 20 to 30 of these procedures per year at Spectrum Health—and our success rate is upward of 80%.”

The valve can be temporary, operating for three to six months, or permanent, depending on the patient’s needs.

“I’m 6-foot tall, but by the time I met Dr. Cumbo-Nacheli, I had dropped down to 120 pounds,” Hitts said. “When I heard about the Zephyr valve, at first it seemed like I was too far gone for that. But I passed the evaluation and I was ecstatic. I just wanted to live. I wanted to work again.”

The valves are installed in a 30-minute endoscopic procedure. The patient then stays in the hospital three days for observation.

Follow-up appointments are scheduled for three to six months, then once a year.

A life regained

After the procedure at Spectrum Health Butterworth Hospital, Hitts spent the next three days at the hospital with no signs of complications.

Finally, he could breathe deeply.

“I owe Dr. Cumbo-Nacheli my life,” Hitts said. “Sure, I still have some bad days. But those are because of allergies, not COPD. And I’m working again, full-time. I’m hunting and fishing with my grandkids again.”

He quit smoking and he also gained back some weight.

“Guess now I should lose some weight,” he grinned. “It used to be hard to eat because I couldn’t breathe, but now I can eat again. I can do everything.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

How precious to have more time with Paul!

Thank you Dr Cumbo-Nacheli.