Like a world traveler, Mary Matzen made frequent trips all her life.

Unfortunately, most of them were to the bathroom.

“When I was a kid, I noticed that I was always looking for a bathroom,” Matzen said. “As a teenager singing in church choir, I would go to the bathroom before choir. By the time the sermon was over, I was desperate to get up and go.”

Matzen suspects much of it may have been psychological.

Growing up, her mom always encouraged her to hit the potty, more out of caution than necessity.

“My mother would make us go to the bathroom, whether we had to go or not,” Matzen said. “I’ve read up on it. You’re not supposed to force yourself to go. I’ve had bad bathroom habits my whole life.”

Matzen, now 70, has taken more trips to the lady’s room than she’d prefer to count.

“I was going every hour on the hour,” the Jenison, Michigan, resident said. “If I drank a cup of coffee or glass of water, I’d have to go to the bathroom in 30 minutes. Liquids have always gone through me like that. As you get older, it gets worse.”

Matzen grew up in Kentucky and she often visits family there.

She likes to joke that she knows every bathroom stop from the Great Lakes State to the Bluegrass State.

“There’s no place in West Michigan that I don’t know where the bathroom is, or if it’s a nice one or not,” Matzen said. “There’s no place between here and Kentucky. I know where every bathroom is in the state of Indiana. Trust me.”

Structural problems

Matzen had a baby at age 35 and she had her tubes tied a year or so after that. She also had a hysterectomy a decade ago.

Consequently, she suspects she developed structural problems from those events.

It doesn’t help, she thinks, that she spent her career climbing telephone poles and hoisting 70-pound ladders. Or spending the last two decades on her feet during work hours.

“I have had a lot of wear and tear on my body,” she said. “I really enjoyed climbing telephone poles. Of course, I didn’t realize what it had done to my body until I was old.

“Nothing was being held in place anymore like it should be,” she said. “Everything is probably laying down there on my pelvic floor.”

In her 50s, she started experiencing what felt like a bladder infection. She made an appointment with a urologist.

“There was fullness,” she said. “I would get pains. Shooting pains. He sent me to physical therapy. He said, ‘You have a pelvic floor dysfunction, you don’t have anything wrong with your bladder.’ It settled down and I didn’t have any trouble for a year.”

But as she neared her 60s, more problems.

“One of my hips started going bad,” she said. “I started to walk differently—and that throws your whole pelvic area off.”

With an out-of-control bladder and failed treatments, Matzen turned to Elizabeth Leary, MD, and nurse practitioner Kathleen Hascher, NP, both urogynecology specialists with Spectrum Health Medical Group.

“Mary has an overactive bladder,” Hascher said. “Bladder function is a complex interaction between the bladder, brain, spinal cord and peripheral nerves. Usually, a healthy bladder expands with urine once it’s half full. The nerves in the bladder send the signals that tell a person that it is time to urinate.”

With an overactive bladder, the coordination between the different pathways does not work properly.

“The bladder nerves constantly send signals to empty the bladder even when it is not half full,” Hascher said. “It is a common cause of urinary incontinence.”

About 1 in 3 adults age 40 and older report symptoms of an overactive bladder at least sometimes, according to Hascher, with as many as 46 million people in the United States—30 percent of men and 40 percent of women—suffering from the condition.

Electrical stimulation

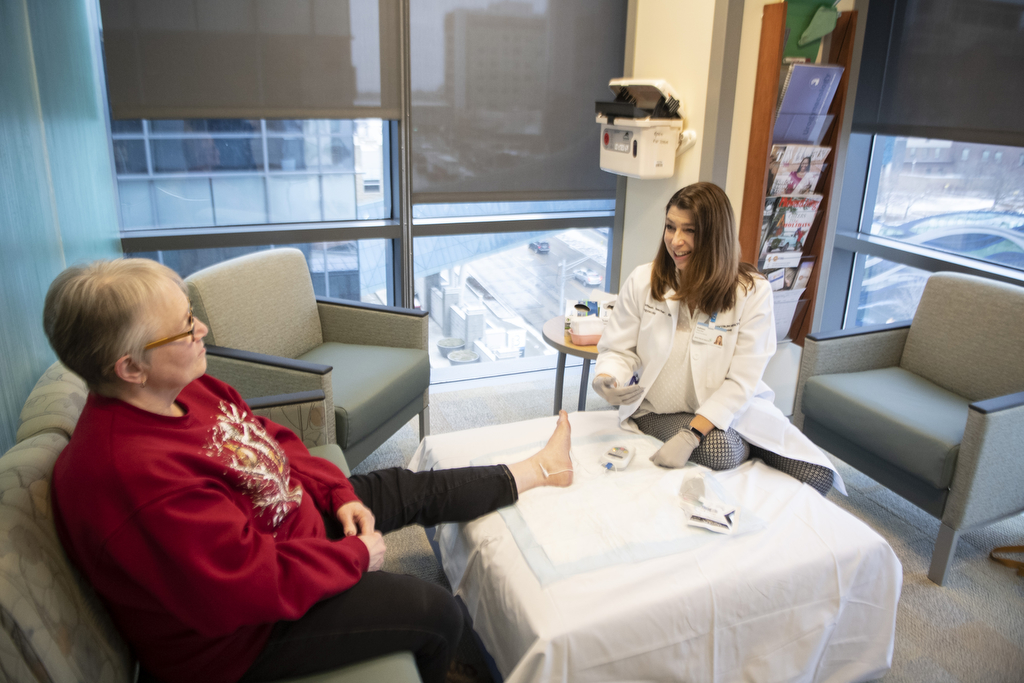

Hascher started percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation treatment on Mary. This low-risk, non-surgical treatment uses a needle similar to acupuncture to electrically stimulate the nerves responsible for bladder and pelvic floor function.

During the 30-minute treatments, Hascher would elevate Matzen’s foot, then insert a small needle electrode near the tibial nerve in the ankle. She connected a stimulating device to the electrode and sent mild electrical pulses to the tibial nerve.

The impulses traveled to the sacral nerve plexus, the group of nerves at the base of the spine responsible for bladder function. By stimulating these nerves, bladder function can be changed.

Because it’s a gradual change, patients receive a series of half-hour treatments, once a week for 12 weeks. Up to 80 percent of patients experience improvement in their overactive bladder symptoms.

Matzen said she can’t feel the electrical impulses in her bladder during treatment.

“I feel it just in my ankle,” she said. “It deadens the nerve so your bladder is not constantly feeling like it has to go. The least little bit of liquid and I feel like I have to go to the bathroom. Or, I did.”

Some patients, like Matzen, require more than 12 weeks of treatment. But she reports a 90 percent improvement.

“It has helped a lot,” Matzen said. “I don’t worry about it like I used to. I can put a pad on (for emotional security) and go to a meeting without having to worry about jumping up in the middle of it and running out.”

Instead of dashing to the restroom “every hour on the hour,” she can now go several hours without a pit stop.

“I’m not constantly in the bathroom all the time and I don’t have the zinging anymore,” Matzen said.

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

I have had an overactive bladder more of my life, especially experiencing urgency. I am now 90 and after 5 children now have been prescribed Vesticare which helps somewhat. Any help for a person like me or a more effective medication and or a cheaper one?

I never knew the sciatic had anything to do with your bladder

I would like more information about this procedure. How could I achieve that???

Hi Susan – You can learn more at the Spectrum Health urogynecology website – https://www.spectrumhealth.org/for-health-professionals/referrals-and-consultations/womens-health/urogynecology – or call 616.391.3304. Best wishes to you.