Cheri Compton remembers that day in May 2012 like it was yesterday.

After playing in the backyard with her sons, she went inside to get a drink and rest, hoping to ease the dizziness and nausea she’d felt for hours.

The next thing she knew, her son, then 5, shouted “Mom!” in her face. He told her she’d been shaking a lot and she’d fallen asleep and wouldn’t wake up.

Compton felt sore in every muscle. She seemed confused about what had happened. And scared.

She later learned she had suffered a seizure—specifically, a tonic-clonic seizure, formerly called a grand mal.

A tonic-clonic seizure is what most people think of when they picture a seizure. A person loses consciousness, muscles stiffen and the body jerks with convulsions.

Unfortunately, that first seizure wouldn’t be her last. She endured many more before finding doctors who would help her reclaim her life.

Today, nearly six painful and life-altering years later, Compton is doing much better thanks to a surgery performed by Spectrum Health neurosurgeon Konstantin “Kost” Elisevich, MD, PhD. The surgery, called brain resection, removed the part of her brain that triggered her seizures.

She admits she is now a different person than the 27-year-old woman who stood in her backyard that May afternoon.

“It changed my whole world,” said Compton, who lives in Holland, Michigan, with her husband, Tim, and sons, Henry and Sam.

Before the seizures, she had been finishing the final year of her bachelor’s degree in accounting, with a goal of earning her license as a certified public accountant.

“It all just stopped,” she said.

Auras

After that initial incident, Compton suffered another seizure three months later, prompting her neighbor to call 911. It landed Compton in a neurologist’s office, where doctors diagnosed her with epilepsy.

Doctors prescribed her medication, but that fall she had another seizure. It caused her to hit her head on the kitchen counter, chew up her mouth, bruise her ribs and wake up in bed, confused about how she got there.

Under the care of an epileptologist, she got a prescription for another medication that would stop the tonic-clonic seizures for a time.

Still, she continued to have auras, a more minor seizure that created a rising feeling in her stomach and a dizzy, vibrating feeling throughout her body.

She remembers having her first aura in July 2010 during a study abroad trip to London. Looking back, she suspects she had about a hundred of them long before that first tonic-clonic seizure in May 2012.

In an effort to control the auras, her doctor increased her medication dosage. It triggered extreme nausea, which wiped out her desire to eat.

The doctor reduced the dosage again. Sure enough, she experienced another severe seizure—this time while driving. She had gotten permission to drive 11 months prior and had done so without incident until that day. Luckily, she only crashed into a snow bank on a side street and didn’t injure herself or others.

As doctors continued to adjust medications, Compton continued to have seizures. Except now they were complex partial seizures, typically triggered while eating or drinking.

During these less severe seizures, she sometimes became unresponsive to the people around her, or made repetitive noises or motions, or walked around and did strange things.

By then Compton’s condition had led to plenty of difficulties. She stopped driving again. She saw some friendships fade. She embarrassed herself in public situations, including at her sons’ school and at the beach during an amazing Lake Michigan sunset.

She felt scared to eat or drink in public, worried it would set off a seizure.

In 2015 she experienced more than 100 seizures, including 21 in one week alone that summer.

She also married Tim that year, the man she had loved since age 17. She didn’t eat during the formal dinner at her wedding, fearing the worst. Instead, she waited to eat until most of the guests went home.

“That’s the kind of fear that took over my life,” she said.

Compton grew depressed and began to feel hopeless about ever getting back to her life. She took so many anti-seizure medications, she could barely function.

Something had to change.

Surgical solution

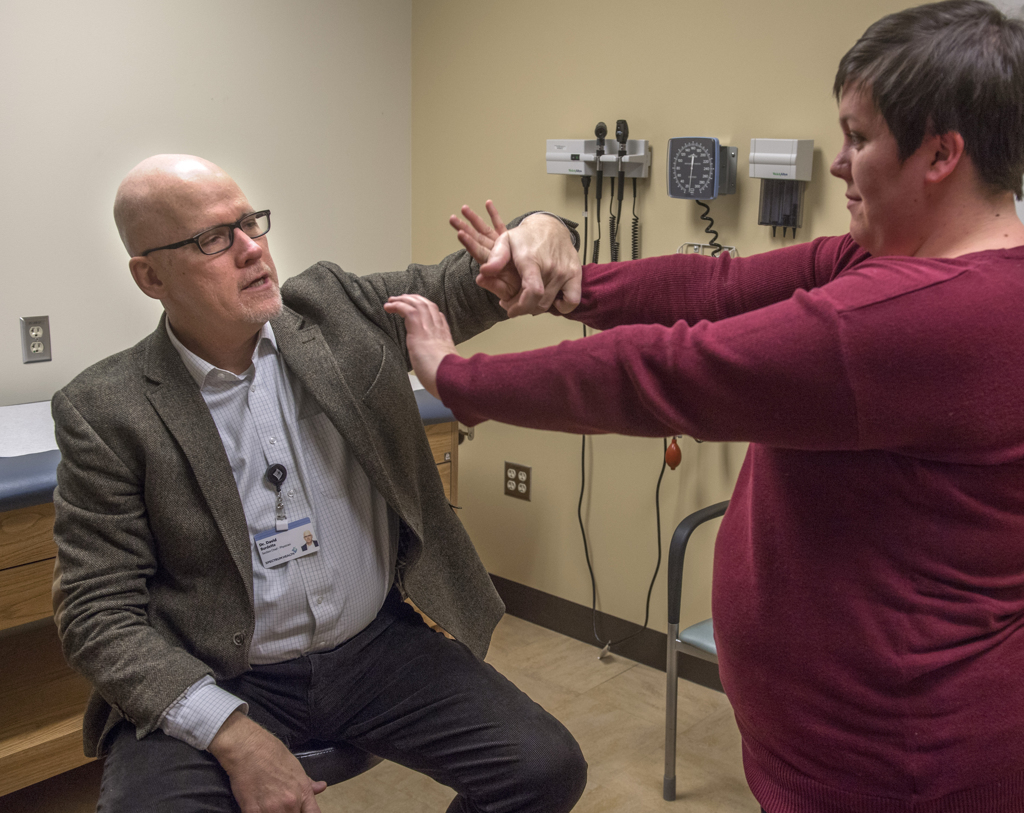

About three years ago, Compton sought the help of Dr. Elisevich, Spectrum Health neurologist David Burdette, MD, the epilepsy section chief, and Spectrum Health neuropsychologist Michael Lawrence, PhD.

Compton’s new doctors began to explore the possibility of surgery.

“It wears you down,” Dr. Burdette said of the disease. “People can become agoraphobic, afraid to go out because they never know when or where a seizure is going to hit. Cheri is very outgoing and vivacious. She likes to grab her life by the scruff of the neck and get the most out of it. She was significantly debilitated by her seizures.”

Doctors began a battery of tests that lasted nearly a year.

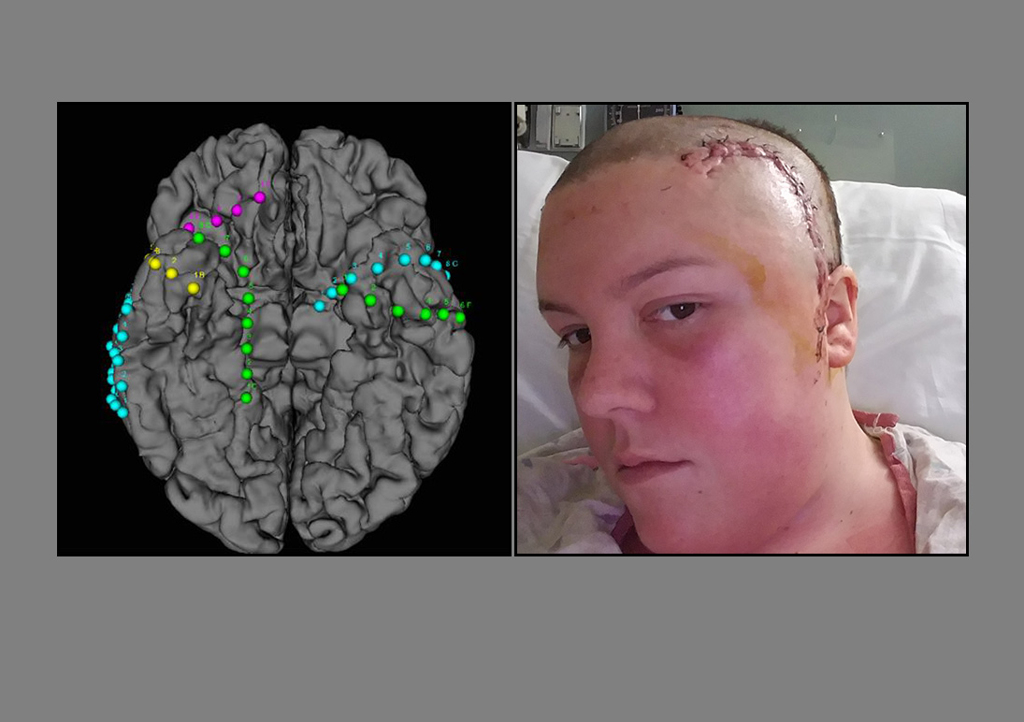

In November 2016, doctors admitted her to Spectrum Health’s Epilepsy Monitoring Unit, where they surgically implanted electrodes on her brain’s temporal lobes. The electrodes recorded vital information each time she had an aura or seizure. This data helped doctors isolate the part of her brain responsible for the seizures.

The monitoring lasted two and a half weeks. Friends, family, people from her sons’ school and others rallied around her, Tim and their sons.

“I am incredibly lucky to have the people I have, showing me their love,” she said.

Finally came some news—good, but also terrifying.

Other options

In addition to brain resection surgery, there are other epilepsy treatments available. For patients whose seizures are triggered in several parts of the brain, or in areas too sensitive to remove, the NeuroPace Responsive Neurostimulation System might be the answer.

The device, implanted in the skull, detects abnormal electrical activity in the brain and responds by sending electrical stimulation to stop a seizure before it starts.

“It is a closed-loop system embedded in the brain that will provide surveillance of electrical activity and abort a seizure when one is identified,” Dr. Elisevich said.

Another option: vagus nerve stimulation, in which doctors implant a small device around the vagus nerve in the neck. While it won’t cure epilepsy, it can reduce the frequency and intensity of seizures in certain patients. Also, its effectiveness improves over time, Dr. Elisevich said.

The doctors had obtained the information they needed to proceed with surgery. Compton’s seizures arose from the temporal lobe, the most common site of origin, according to Dr. Burdette.

“We identified that she had a fairly restricted area of seizure onset in the temporal lobe,” Dr. Elisevich said. “We were going in simply to remove only as much tissue as it takes to stop the epilepsy.”

They scheduled the surgery for Dec. 2, 2016.

“I put my trust in him and hoped for the best,” Compton said.

Hopeful future

Two days after surgery, Compton left the hospital. Since then, she has not had a single complex partial or tonic-clonic seizure.

She still suffers from auras, but they are much less frequent. Unfortunately, they’re getting longer and more intense as time since the surgery passes, so Dr. Burdette has changed her medication with the hope of reducing them. She also struggles with memory issues and word recall, a common side effect.

While the auras are a discouraging setback, she’s trying to stay positive and focused on getting back to life—even the simple things others take for granted.

She goes to restaurants with family and friends. During tax season she stays busy completing work for clients. She volunteers in her boys’ school.

“The emotions from even a small regression like this are overwhelming,” she said.

She worries about the future.

“It’s still hard,” Compton said. “I worry about it being something that will continue to change in my brain.”

To help others on the same journey, she attends a support group and formed a new support group for epilepsy patients in the Holland area. She also accepted an invitation to represent the neurology department on the Spectrum Health Patient and Family Advocacy Council last year.

“I like that Spectrum Health listens to their patients and tries to make the system work better for them,” she said. “If I can use what I have gone through and turn it into a positive, then it makes me feel better about all of it.”

She urges others with epilepsy to fight for a solution that works for them. Through it all, she said, patients should strive to focus on the good in life—even in extremely difficult times.

Dr. Burdette agrees.

“It is not acceptable to be having one seizure a day, a week, a month, a year,” Dr. Burdette said. “We need to get those seizures under control. The first line of defense is medications, but if they prove to be ineffective, there are other options.

“It’s a big step, and it can be a scary step, but people like Cheri have done it,” he said. “And they are more than happy to talk with others.”

For Drs. Elisevich and Burdette, it’s gratifying to see patients like Compton.

“The thing that impresses all of us is the fortitude of the patient,” Dr. Elisevich said. “To go through the process with us takes months before we are confident in what we need to do, and they are confident in us. That’s not a trivial thing. I really have to give it to them to get through this whole thing.”

It’s people like Compton who keep him going, Dr. Burdette said.

“There is such a great feeling to see someone who has so much potential, and that potential was being stifled by such frequent seizures,” he said. “To see that turn around, that’s why I do what I do.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

Cheri is our niece and I am so proud of her. Thank you to the doctors who are diligently working to improve a “normal” life for patients with epilepsy.

I just saw this comment, but thank you Aunt Sandy. I always feel your love!

Dr. Elisevich did this surgery on me for the same thing in 1995. It seemed like a miracle to not have seizures after years of feeling so miserable. It is fantastic to now have him at Spectrum.

How wonderful, Cheryl. It sounds like a miracle indeed. Thank you for your kind comment, and for being a Health Beat reader! Cheers, Cheryl (Health Beat editor)