Before Pat Ringler showed up at his restaurant one August morning, he hadn’t spoken to anyone.

So no one knew exactly when his symptoms started.

But bartender Emy Tavis knew one thing when she saw him fumbling at the side door, trying to come in just before 10 a.m.: Something wasn’t right.

As she opened the door for him, “it was almost like he was trying to walk right through me,” she said. “He was looking at me, but he wasn’t really looking at me, like he was not there.”

Pat, 61, owner of the Chase Creek Smokehouse in Chase, Michigan, said something unintelligible and walked to the coffee pot.

“He started to pour, and he’s looking at me and I’m looking at him, and he just drops the coffee cup,” Tavis said.

Seeing the left side of his face droop, she ran to grab the kitchen manager, Bonnie Wallace.

Speed and teamwork

Ever since a relative’s stroke, Wallace had kept a stroke awareness flyer posted on the kitchen whiteboard. She recognized Pat’s symptoms and called 911. An ambulance arrived from Reed City and took him to Spectrum Health Big Rapids Hospital, where emergency room doctor Brad Huizenga, DO, was on duty.

Recognizing stroke symptoms, Dr. Huizenga ordered a CT scan of Pat’s brain and asked the EMT crew to stand by.

“We said, ‘Hold on. You guys have to stay here because there’s a good chance he’s gonna be transferred for clot removal,’” Dr. Huizenga said.

But first Dr. Huizenga would need to determine whether his patient qualified for an intravenous clot-dissolving drug called tPA.

Since the medication must be administered within four and a half hours of the onset of stroke symptoms, the doctor asked Pat’s employees and family to help pinpoint his “last known well” time: Had anyone been in contact with him by phone that morning? Had anyone seen him before he showed up at the restaurant’s door?

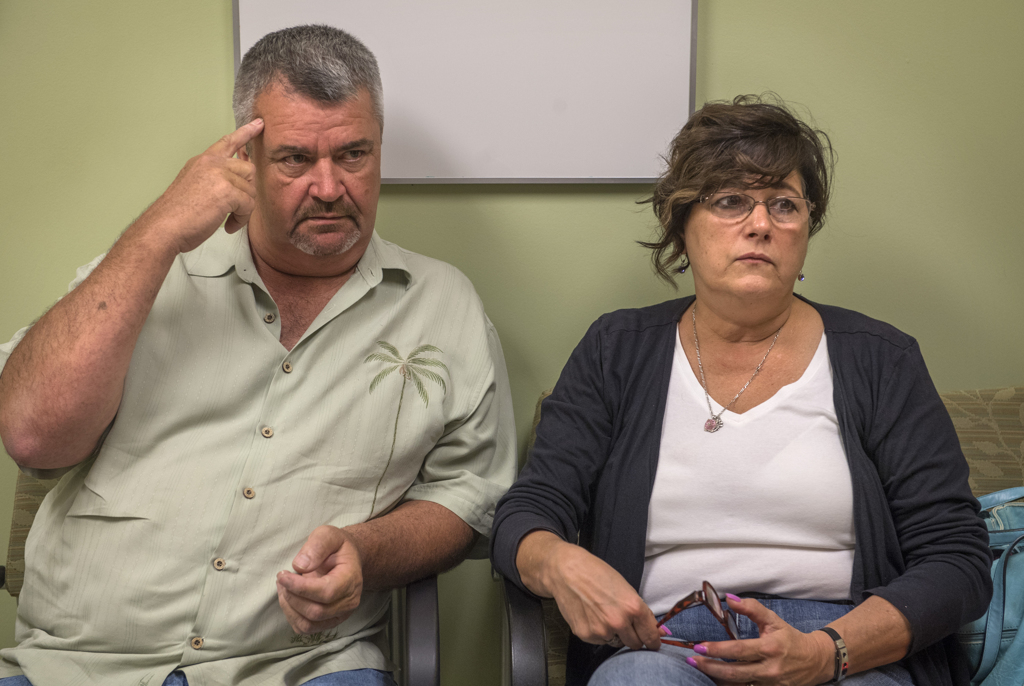

Pat’s wife, Linda, arrived at the ER from Ferris State University, where she was helping her son move in. She said that while she hadn’t seen her husband that morning, they had exchanged text messages at 9:30 a.m.

“He and I had been texting back and forth about fixing this beer cooler outside. It may not make sense to you, but it makes perfect sense to me,” she told the doctor. “It’s a lucid conversation.”

Dr. Huizenga got on the phone with Muhib Khan, MD, the vascular neurologist at the helm of the comprehensive stroke center at Spectrum Health Butterworth Hospital that day.

“It seemed to me that with the kind of paralysis he had on one side of his body, he probably wouldn’t be texting,” Dr. Huizenga said. Perhaps they could consider 9:30 Pat’s last known normal. This would place him well within the tPA window.

Dr. Khan agreed. He gave the Big Rapids team the go-ahead to start the clot-busting drug and get Pat on his way to Grand Rapids.

“If you have major stroke symptoms and you are getting tPA, we are not going to wait for the tPA to kick in,” Dr. Khan said. “We know it doesn’t completely dissolve the clot in about 85 to 90 percent of patients.”

Clot retrieval

Once at Butterworth Hospital, doctors rushed Pat in for a new set of scans to locate the clot and assess the state of his brain. They found a major vessel blockage in his middle cerebral artery, which put him at risk for extensive brain damage.

The only way to save the brain was to pull out the clot.

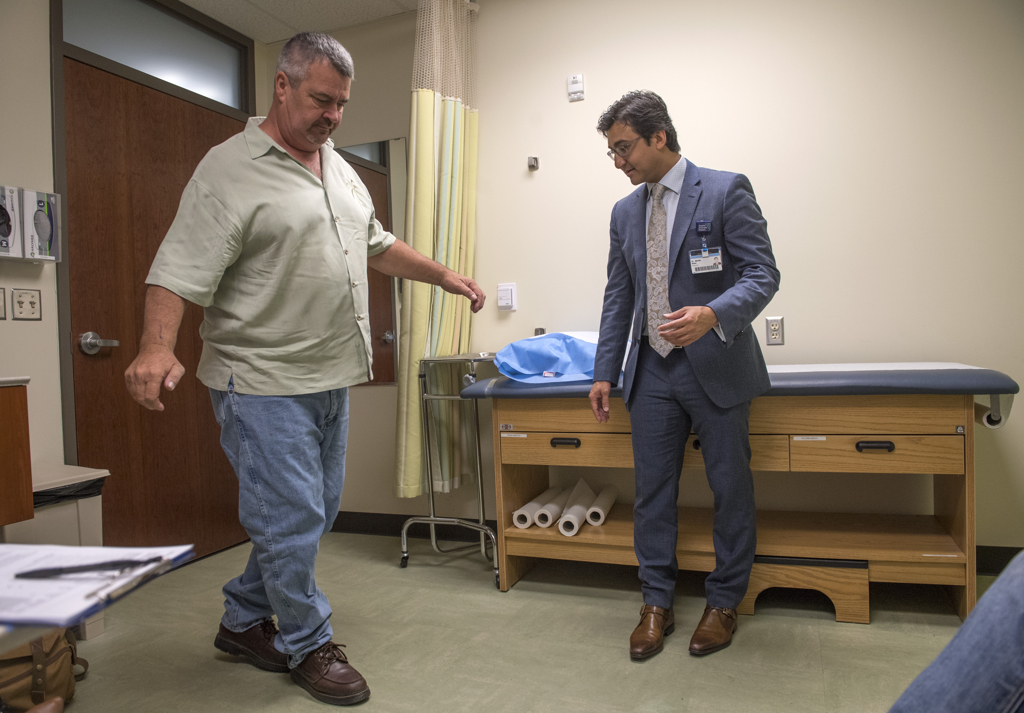

Justin Singer, MD, a Spectrum Health Medical Group neurosurgeon, stood ready to perform an intervention called a thrombectomy.

“It was almost like on TV,” Linda said. “We’re like almost running down the hallway behind the gurney, because they’re in such a hurry to get him to the OR.”

Dr. Singer inserted a catheter into an artery in Pat’s groin, threaded it up to the site of the clot, then snaked a tiny stent retriever up the tube to grab the clot.

Within 10 minutes, the clot was out and the blood vessel was clear. The thrombectomy restored full blood flow to Pat’s brain, limiting the stroke’s effects.

Ready to go

The effects were in fact so minimal that when he woke up in the ICU, Pat told his wife he was ready to put on his pants and go home.

“I’m like, ‘Well, Honey, I don’t think that’s gonna happen today,’” she said.

But two days later, it’s exactly what happened.

And the following Monday, just four days after his stroke, Pat went back to work at his restaurant—mowing the grass, changing lightbulbs, even climbing on the roof of the smokehouse as Tavis stood in tears below, begging him to come down.

“He really does what he wants,” Linda said, shaking her head.

The way Pat sees it, he has no reason to change his routines.

“Lots of people don’t even think I had a stroke as severe as what I had—because I’m fine,” he said.

Though he doesn’t like thinking about what might have been, he knows the outcome could have been devastating if Tavis and Wallace hadn’t been around that morning.

“If they wouldn’t have got me to the hospital in time, I think I’d have been really messed up,” he said.

“I mean, I was screwed up at the time. Nothing worked. This side of my body didn’t work, I couldn’t see out of this eye. So it got me pretty good.”

This is a case where everything went just right for the patient, Drs. Khan and Huizenga agreed.

A prompt call to 911. A speedy evaluation at the regional hospital. Immediate communication with the on-call stroke doctor. Close collaboration between the two hospitals. An expedited transfer to the stroke center. And a successful opening of the vessel.

Looking back on that chaotic day, Tavis, Wallace and Linda are amazed at how all the pieces fell into place for Pat.

“(Everyone) did everything they were supposed to do,” Linda said. “I couldn’t be more grateful.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>