Christine Fredricks felt a rush of anxiety when she discovered she had COVID-19.

As a breast cancer survivor, she feared she could be at greater risk for severe illness from the virus.

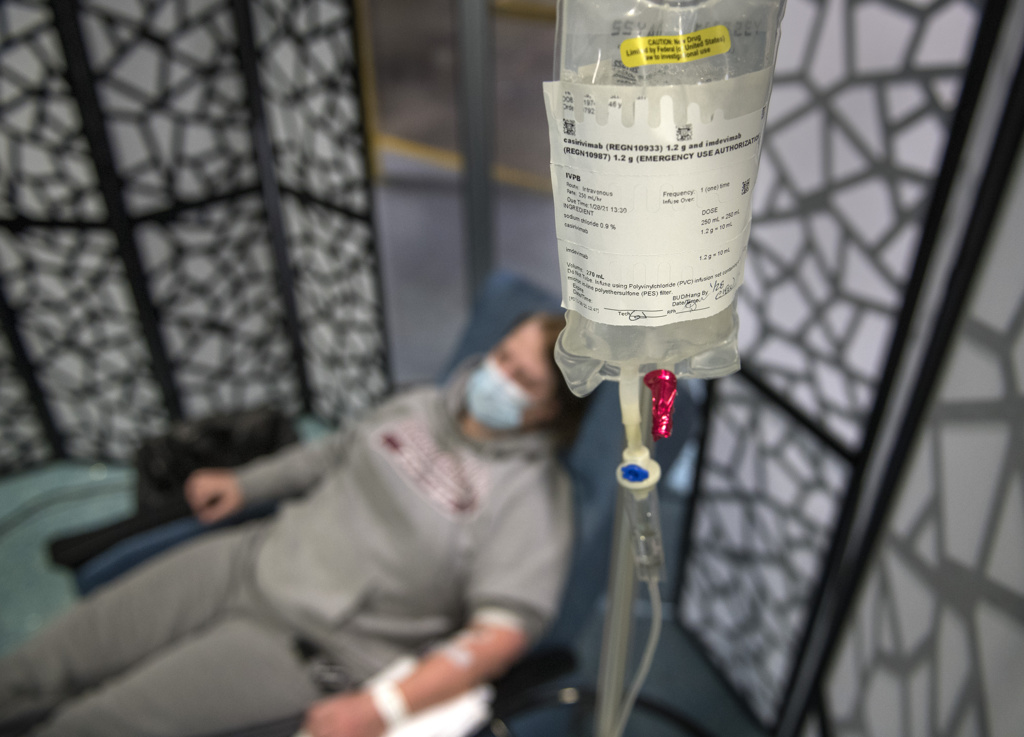

That’s why she agreed with her doctor’s suggestion to receive an antibody treatment that aims to boost her body’s ability to fight infection.

“Since my immune system is weaker, I am hoping other antibodies will take effect and help create what I need to beat (the virus),” Fredricks said.

She received the infusion at a Spectrum Health outpatient clinic that provides monoclonal antibody therapy.

The treatment, which has received federal emergency use authorization, is a significant development in the fight against COVID-19, said Gordana Simeunovic, MD, an infectious disease specialist leading antibody therapy treatments for Spectrum Health.

“This treatment is meant for patients who have risk factors to develop severe disease,” she said.

“It is very exciting because it can be used in an outpatient setting. Our goal is to give this to people in the early course of the disease—and to prevent them from becoming sicker and requiring hospitalization.”

Monoclonal antibodies are man-made proteins that act like human antibodies in the immune system. The therapy received public attention when former President Donald Trump received Regeneron monoclonal antibodies after his COVID-19 diagnosis.

The treatments have a similar aim as convalescent plasma therapy—in which patients receive antibody-rich plasma donated by COVID-19 survivors.

The monoclonal antibodies are intended to “do exactly the same thing,” Dr. Simeunovic said. The treatment is designed to use antibodies to “find the virus, kill the virus and prevent the virus from causing severe disease.”

But while plasma therapy can only be given to hospitalized patients, monoclonal antibody therapy can be administered in a single infusion in an outpatient clinic.

A move to a bigger clinic

Spectrum Health opened the outpatient infusion clinic Dec. 8. By the end of January, more than 190 patients had been treated.

“Our results have been really encouraging,” Dr. Simeunovic said.

Preliminary data shows the therapy has reduced hospitalization or emergency room visits in patients at high risk for severe illness.

The clinic is moving to a larger location at Spectrum Health Blodgett Hospital to accommodate more patients.

The infusion treatments include Eli Lilly’s Bamlanivimab and Regeneron’s Casirivimab and Imdevimab.

Dr. Simeunovic described the difference between the treatment and the COVID-19 vaccine.

The vaccine is given to healthy patients to stimulate their immune system to produce antibodies to protect them from the virus.

In monoclonal antibody therapy, an infected patient receives antibodies designed to attack the virus immediately. They help fight infection while the patient’s immune system ramps up its own antibody production.

Dr. Simeunovic addressed a concern she often hears from patients considering monoclonal antibody therapy: Can they still get the COVID-19 vaccine?

The answer is yes.

“If you get monoclonal antibodies, you can still get the vaccine. The only thing is that you have to wait 90 days,” she said. “But for this 90 days, you have antibodies that your body made to protect you.”

To be eligible for the outpatient monoclonal antibody infusion, patients must be 12 or older, test positive for COVID-19 and have symptoms present for fewer than 10 days.

The patients must also have a risk factor for disease progression, including:

- Significant immunosuppression

- Morbid obesity

- Uncontrolled diabetes

- Chronic kidney disease

- Heart disease

- Lung disease

- Age 65 or older

Anyone who meets the criteria may contact the COVID-19 Infusion Clinic at 616.391.0351 to be screened by the clinic team for possible treatment.

Patients receive the infusion in a single, three-hour appointment at the clinic. It takes about one hour to receive the infusion. Patients remain for an hour afterward for observation.

An unexpected diagnosis

Fredricks was taken by surprise when she learned she’d contracted the virus.

On Friday, Jan. 22, she had a COVID-19 test in advance of scheduled breast reconstruction surgery. She had no symptoms at the time.

The next morning, she woke up with a headache. And when she checked her MyChart account, she discovered she’d tested positive for the COVID-19 virus.

She soon developed other symptoms, including congestion, a cough and chest pain. She lost her sense of taste and smell.

“And I had a massive, massive headache,” she said. “My head felt like it was going to absolutely explode.”

On Tuesday, Fredricks went to a Spectrum Health emergency department, worried about the severe headache, as well as shortness of breath and chest pain.

While not ill enough to be admitted to the hospital, her doctor and the emergency department medical team suggested she consider the monoclonal antibody infusion.

She hesitated at first, concerned about possible side effects.

Some patients develop an allergic reaction to the treatment. That reaction may be mild, such as irritation at the injection site. In rare cases, a severe allergic reaction called anaphylaxis can occur.

“Based on our experience and the data we have, these side effects are rare,” Dr. Simeunovic said.

Fredricks decided she was more worried about her ability to fight the COVID-19 infection than about potential side effects of the treatment.

Diagnosed with breast cancer in 2018, she underwent a double mastectomy. Although she has been in remission since 2019, she said, “With my history of cancer, my immune system is not up to par.”

Five days after learning she had COVID-19, Fredricks arrived at the infusion clinic for her appointment.

The hourlong infusion passed quickly.

“It was easy-breezy,” she said. “I had no problems.”

That night she slept nine hours, her first solid sleep since she fell ill.

And the next day, her headache had almost disappeared.

“I just have a little congestion,” she said. “I’m still a little tired. Other than that, I feel good.”

Questions and relief

Patients who are considering the therapy are first screened by clinical research nurses to see if they are eligible.

“A lot of patients have a lot of questions, which is good,” said Brianna Barber, RN.

But the nurses also hear relief from many patients who are worried about how COVID-19 will affect them.

“I think with some of their underlying conditions, it makes them feel better to get this new treatment,” nurse educator Alison Dutkiewicz.

“It makes COVID-19 less scary to know they can do something about it.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

Good to know about this.