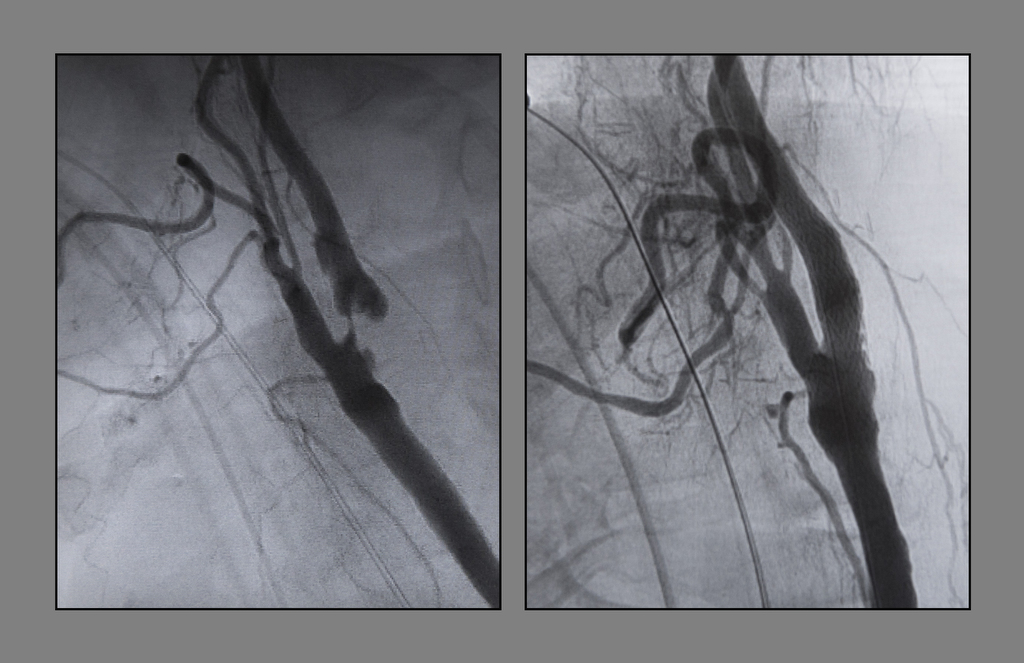

Even to an untrained eye, the blockage in Lester Cramer’s left carotid artery looked dramatic.

In the black and white image from his scan, the artery leading to his brain looked like two separate rivers, linked by a thin, trickling stream.

In that spot lay a lesion blocking at least 90 percent of the blood vessel, leaving him at risk for a stroke.

“It’s kind of nasty looking there on the scan,” said Cramer, an active 76-year-old from Barryton, Michigan. “I bet it isn’t a third of the size of the other (carotid artery).”

To open up the artery and reduce his stroke risk, Cramer became the first patient at Spectrum Health to undergo an innovative procedure―called TCAR, for transcarotid artery revascularization.

The procedure involves placing a tube in the artery to temporarily direct the flow of blood away from the brain while the surgeon places a stent. The reversal of blood flow is designed to protect from any plaque that could be dislodged during the procedure.

This is a life-saver, no doubt about it.

Blood from the artery flows into a tube, runs through a filter to remove debris, and then is fed back into the body through a vein in the groin.

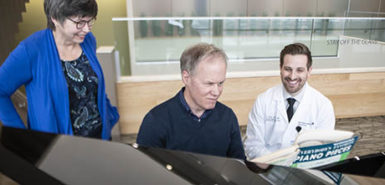

The approach “is really a significant step forward,” said Jason Slaikeu, MD, FACS, division chief of vascular and endovascular therapy at Spectrum Health. “It definitely is a novel, progressive technique.”

Dr. Slaikeu is one of 100 surgeons in the country trained in the new procedure developed by Silk Road Medical.

The approach does not replace traditional techniques for opening blocked arteries, Dr. Slaikeu said, but it provides an excellent alternative for many patients.

“In select patients, I think this is going to see significant growth,” Dr. Slaikeu said.

A mini stroke wake-up call

Cramer had no idea of the risk brewing in his carotid artery until four years ago, when he almost fainted while driving his wife, Linda, to the doctor’s office. He pulled over and got out of the car.

And he made an appointment with his doctor. The verdict: He had suffered a mini stroke. And tests showed a dangerous blockage in his left carotid artery left him at risk for future strokes.

There definitely are people like Mr. Cramer who are at high risk for other carotid procedures and would benefit from having this option.

He underwent surgery to open the artery and clear the blockage.

Three years ago, he suffered a heart attack that thankfully did not do much damage. He underwent quadruple bypass surgery.

Since then, Cramer has continued chopping firewood, hunting, fishing and enjoying life on the 40 acres of land he calls home.

He started eating more vegetables and high-fiber foods and cutting back on sweets.

“I grew up on meat and potatoes,” he said. “But I’m trying to change my eating habits.”

A 40-year smoker, he had kicked the habit in 2000.

His doctor continued to monitor his carotid artery, and recently recommended surgery for a second time.

“When he showed a CT scan of my neck, that made a believer out of me,” Cramer said.

Weighing the options

The lesion in Cramer’s artery was especially complex, said Dr. Slaikeu, who examined his test results with a Spectrum Health multidisciplinary team dedicated to treating carotid artery disease. The team brings together experts in vascular surgery, neurology and neurosurgery who collaborate in evaluating complex cases and determining the best treatment.

He had a new narrowing in the area where he had previously undergone surgery. And he had a dissection―a flap in the wall of the artery.

“Given the fact that he had both a dissection of the artery and a narrowing of the artery, his risk of having the artery completely blocked was significant,” Dr. Slaikeu said. “We felt strongly as a team that he needed to have an intervention to reduce his risk of having a disabling stroke or a life-threatening stroke.”

Traditionally, Cramer would have faced two choices: undergoing surgery like the one he had four years ago, or having a stent placed in the artery via a catheter that is inserted in the artery in his groin.

Surgery would be challenging because his doctor would have to make an incision through scar tissue from the previous operation, Dr. Slaikeu said. And Cramer would be at a higher risk of suffering nerve injury.

A traditional stent placement also would have posed risks of dislodging plaque, which could cause a stroke.

His medical team decided the innovative TCAR procedure offered his best option.

First, a dry run

On Jan. 10, 2018, the day before Cramer’s operation, a surgical team gathered in the Jacob and Lois Mol Cardiovascular Simulation Center.

Dr. Slaikeu, who has had extensive training in the procedure, led a practice session in the simulation center.

The surgical team donned gowns, gloves, masks and lead aprons and gathered around a mannequin that lay on the operating table. The patient was made of plastic and metal, but everything else―from the equipment to the steps followed during the simulated procedure―was real.

The run-through gave everyone involved, including the surgical technologist, nurses, anesthesiologist and surgeons, a chance to become familiar with the TCAR equipment and procedural steps.

“This is an excellent example of the role of the cardiovascular simulation center in improving patient care through the ability to perform interdisciplinary team training,” said Robert Cuff, MD, the director of the center. “Dr. Slaikeu’s team was able to rehearse the TCAR procedure, identify any potential issues and improve their technique prior to the first surgery, which improved the chances of this great result for Mr. Cramer.”

Stefan Bordoli, MD, a vascular surgeon who assisted Dr. Slaikeu, agreed: “It’s definitely better to do it first here today. We got a lot of kinks worked out.”

“All of it was done with the intent of reducing the risk of errors and to improve the safety of our patients,” Dr. Slaikeu added.

Before and after pictures

The next day, the same team assembled in an operating room at Spectrum Health Meijer Heart Center to perform the procedure on Cramer’s carotid artery.

Dr. Slaikeu made a small incision just above Cramer’s collar bone and inserted the TCAR device. The other end of the tube was placed into a vein in his groin. Blood flowed away from his brain, through the tube and its filter, and back into his body.

The surgeons placed a stent at the narrow part of the artery, expanding it to make room for better blood flow.

The training and simulation paid off.

“It was beautiful to see how everyone was able to seamlessly and smoothly execute on what was rehearsed the day before,” Dr. Slaikeu said.

Scans taken during the procedure showed the results: The artery now looks like one wide, flowing river.

“It was tremendously satisfying to see the dramatic difference between the before and after images of his carotid artery,” Dr. Slaikeu said.

Feeling a difference

Seeing the before-and-after images made an impression on Cramer, as well. And it made him glad he contacted a doctor after his mini stroke four years ago.

“It’s a wonder I’m alive,” he said. “This is a life-saver, no doubt about it.”

Until they have a stroke, patients often don’t feel any symptoms of carotid artery blockages. But after the procedure, Cramer believes he could tell a difference in his thought processes.

Always a hands-on guy, he used to like fixing things, and felt comfortable working on mechanical, electrical and plumbing devices. But in recent years, he struggled to manage tasks as he had before.

After the procedure, he found himself mulling a plan for a device to feed wood pellets into his furnace.

“I might not ever build it, but my brain is designing it,” he said. “The fix-it part of my brain is working again.”

Stroke prevention

Treating carotid artery disease is crucial to stroke prevention. Each year, strokes affect nearly 800,000 Americans and kill about 140,000, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Strokes also are a leading cause of serious long-term disability.

“Treatment of carotid artery narrowing with medications and surgery is important for preventing stroke,” said Muhib Khan, MD, a vascular neurologist and director of the Spectrum Health Comprehensive Stroke Center. “TCAR is an effective new procedure to help in this regard.”

Research has shown the TCAR procedure reduces the risk of stroke post-surgery, Dr. Slaikeu said.

The stroke risk drops to 1.4 percent from about 3-4 percent for high-risk patients undergoing conventional surgical approach and 6.9 percent from the femoral groin approach, said Dave Jenks, area manager of Silk Road Medical. In addition to temporarily reversing blood flow away from the brain, he said TCAR offers the advantages of being able to eliminate the hazard of navigating a diseased aortic arch and establishing neuroprotection to the brain before treating the lesion with a stent.

“It just provides a greater level of stability,” Dr. Slaikeu said.

During the procedure, doctors monitor patients to make sure the brain receives adequate flood flow from other sources, he added.

“We are excited to introduce this new technology and procedure to our community,” he said. “There definitely are people like Mr. Cramer who are at high risk for other carotid procedures and would benefit from having this option.”

Some patients appreciate the cosmetic difference. The TCAR procedure leaves only a small scar near the collar bone, compared with a longer incision along the side of the neck.

For Cramer, the size of the surgical scar was the least of his concerns.

“At my age, it doesn’t matter,” he said. “I’m just happy to be alive.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

So glad it all went well. Many prayers were said. We love you both Les and Linda.

Thank you Cushman family for all your prayers .

Thank you for sharing your story. I wish you good health in all of your tomorrows! Pam

Thank you Pam for your well wishes .

Thank you Pam we appreciate your well wishes .

We want to thank

Dr Jason Slaikeu and his entire team that did this surgery and we have to Praise the Lord for being with the Doctor and us. Dr.Slaikeu said from the start he would treat us as family and he did just that. Many thanks for family and friends that were there and at home for their prayers and support .

Les and Linda Cramer

Thank you for sharing your story, Les and Linda. It was wonderful to meet you. So glad you are doing well and enjoying life, Les!

Thank you Sue .It was nice meeting you both .Love how the story turned out .Les is doing great after this surgery .

Wow! So happy for you guys! You are always in our prayers!!!

Thank you Jamie and Johan for your prayers