As Lilly Vanden Bosch waited for a blood draw on the 10th floor of Spectrum Health Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital, she scrolled through Florida vacation photos on her iPad, excitedly explaining the scenes.

“See the alligator in the water?”she asked. “I just kept taking pictures. We were safe on an air boat.”

That’s how life has been in the past year for Lilly. A wild ride.

While a life-threatening virus lurked beneath the surface, she remained buoyed by love, optimism, prayers and the steadfast support of family and friends.

A proverbial air boat.

Thankfully for Lilly, who recently turned 11, the danger is almost over. After dealing with a suppressed immune system for many months after a November 2015 bone marrow transplant, she can finally play with friends again, go out to eat, attend parties and go to school.

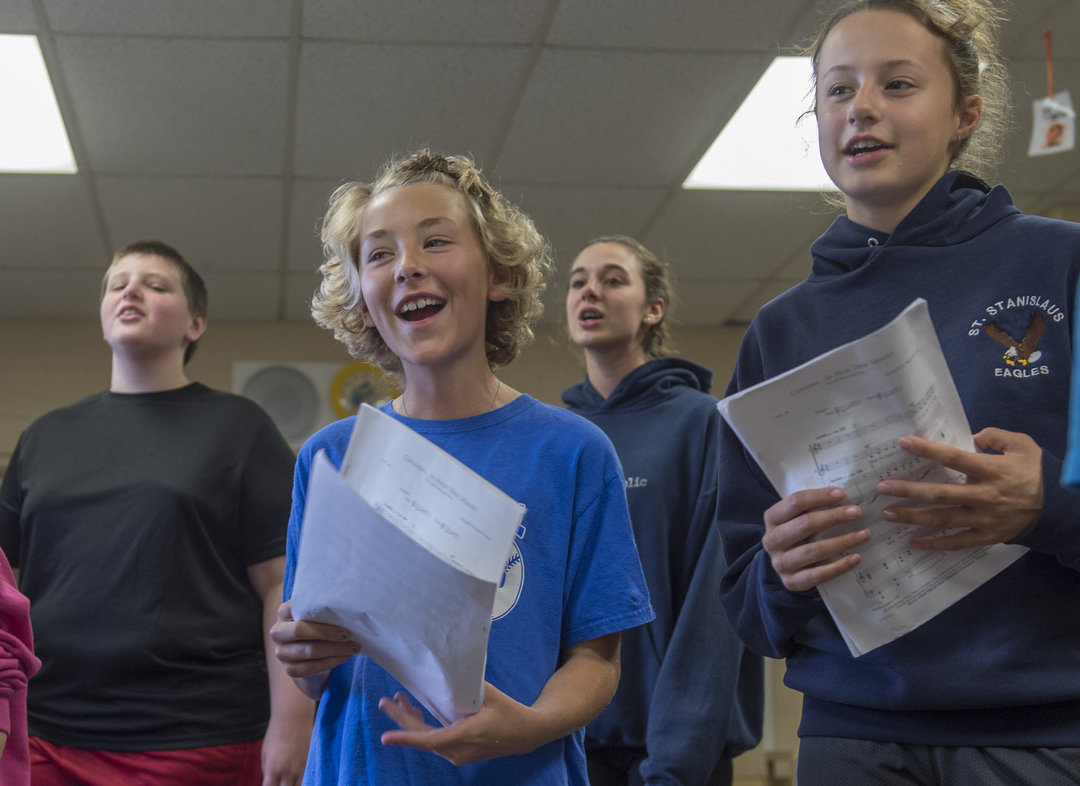

Her once-straight hair has grown back after chemotherapy, framing her face in golden, shimmering curls.

The gamble

Diagnosed with severe aplastic anemia at age 7, Lilly faced a rare and raucous battle against a disease that only two out of every million people are diagnosed with each year.

She underwent chemotherapy and radiation prior to the bone marrow transplant to wipe out her own immune system so it would not battle the cells being introduced from her European donor.

But after a successful transplant, a CMV virus attacked Lilly. And it wouldn’t let go.

It grasped her play time with friends and squeezed the life out of it. She couldn’t risk being exposed to germs. She couldn’t risk being in crowds. She couldn’t shop. Couldn’t swim. Couldn’t eat fresh fruit or drink well water. Couldn’t dine out. Couldn’t go to school.

At the encouragement of Ulrich Duffner, MD, director of clinical services for the Pediatric Blood and Bone Marrow Transplant Program at Spectrum Health Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital, Lilly and her family traveled from their Dorr, Michigan, home to New York City to participate in a promising clinical trial.

Last spring, the family made two visits to the Big Apple for clinical trial treatments. Doctors there infused Lilly with T-cells—a type of white blood cell—from a third-party donor. The clinical trial manipulated those T-cells in the laboratory and trained them to attack the CMV virus.

The CMV virus had threatened the function of Lilly’s new bone marrow because of the antiviral medications needed to keep the virus in check. The medicines prevent her bone marrow from developing like it should, which suppresses her immune system.

The gamble paid off. The clinical trial swallowed Lilly’s CMV virus. It’s gone.

Nothing in life is guaranteed, but the waters no longer appear lined with alligators or other health threats.

“Lilly is doing great and I expect that she just continues to do fine,” Dr. Duffner said. “I think without the treatment of using third-party CMV specific lymphocytes … it would have been very difficult and even not possible to control the CMV infection.”

Dr. Duffner is thankful.

“I’m happy each time I see her, which is the case for all my patients who are in safe waters,” Dr. Duffner said. “It is good to see that she can make plans again and it is not the disease anymore to dictate what needs to happen next.”

Besides continued monitoring at Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital, Lilly is pretty much in the clear.

What a difference a year makes.

The payoff

Last fall, the Vanden Bosch family lived in fear, fear of losing their little blonde-haired, blue-eyed girl. This year, their hearts have been tugged. They realize they have so much to be thankful for.

“Last year we were in the hospital for 50 days,” said Lilly’s mom, Meg. “We were there for Thanksgiving, Christmas and the New Year. Now that we’re coming up on that time of year, everything is starting to remind me of that. …We couldn’t participate in any of that stuff.”

As Meg spoke, Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital nurses prepared to insert an IV into Lilly’s arm. Ashley Kirvin, a member of the Child Life team, stayed nearby.

The New York hospital is still monitoring Lilly, so she visits Helen DeVos every couple of weeks so nurses can draw blood samples.

“The reason for the blood draw is two-fold,” Meg said. “They’re following her immune levels and she has an overload of iron in her blood from all of the transfusions.”

Because the chemotherapy and radiation wiped out Lilly’s immune system, Lilly also needs to be re-vaccinated, as if she were a baby again. She gets vaccinated monthly.

As the nurse tied a blue band around Lilly’s arm, Kirvin coached Lilly.

“Tell your brain, ‘OK, brain, I can do this,’” Kirvin said. “And you can.”

Kirvin handed Lilly a stress ball for her to squeeze, then used an iPad to block the youngster’s view of the needle poke.

Someday soon, these visits will also become a memory. Lilly can’t wait.

She’s also excited to make many new memories.

Instead of lying in a hospital bed like she did last year, for her most recent Thanksgiving, she was at the table, surrounded by family.

“All of the family came,” Meg said. “We’re pretty darn thankful. At this time last year, we didn’t know what was going to happen with our baby.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

Thank Goodness for the good doctors, nurses, and technology at the Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital in MI and Memorial Sloan Kettering Hospital in New York City. So grateful for that cooperation. It does take a Village! Happy Holidays to all!

Another excellent article. Keep it flowing with the current of compassion.

So many members of the congregation I serve have been rooting for Lily to find her way to this day!! May the blessings flow!