When Tara Sweet came down with COVID-19, the illness raised more concerns than it would for most teens.

Born with a rare genetic disease, Tara gets monthly injections to prevent inflammation.

The medication suppresses her immune system—and that raises her risk for complications from COVID-19.

With advice from her medical team, 14-year-old Tara and her parents turned to a new medication in hopes it would help her combat the virus.

She received an infusion of monoclonal antibody therapy, which delivers manmade proteins that act like human antibodies to kill the virus.

Tara is among a handful of pediatric patients who have received the therapy at Spectrum Health.

She shares her story to help spread the word about the treatment, which is available for patients 12 and older who have conditions that put them at risk for a severe case of COVID-19.

“It did help me a lot to recover,” she said.

Tara was a newborn, just 12 hours old, when she developed a rash. For the next 18 months, her parents brought her to various specialists as the rash came and went.

When she was 18 months old, doctors determined she had Muckle-Wells syndrome, an autoinflammatory disease caused by a genetic mutation. It causes periodic flare-ups of skin rash, fever and joint pain.

Without treatment, the syndrome could damage Tara’s organs, said her mother, Kristy Sweet. Doctors said some children lose their vision and hearing by the time they reach adolescence.

Through a study by the National Institutes of Health, Tara began taking a medication that aims to control the inflammation.

“She is doing really well,” Kristy said, noting that Tara has not experienced problems with her ears, eyes or movement.

She keeps busy with school and activities as an eighth-grader at Fruitport Middle School.

“I like spending time with my family and going to church and hanging out with friends,” she said.

Sometimes, she joins her two sisters to lead the congregation in song.

She also plays volleyball, soccer and basketball.

A routine COVID-19 check

To participate in sports, she took a weekly COVID-19 test. And in April, a test came back positive.

“I was shocked because I had no symptoms,” Tara said.

The next day, however, the nasal congestion started. A day later, she lost her sense of smell.

“A day or so after that, I realized that I was getting out of breath every time I walked up the stairs,” Tara said.

Tara had an appointment coming up with Elizabeth Kessler, MD, the pediatric rheumatologist at Spectrum Health Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital who oversees her treatment for Muckle-Wells syndrome.

When Kristy discussed Tara’s COVID-19 illness, Dr. Kessler told her about the monoclonal antibody therapy.

The therapy, which received Food and Drug Administration emergency use authorization, is administered in a single infusion at the Spectrum Health Blodgett Hospital COVID-19 Infusion Clinic.

“The goal of monoclonal antibody therapy is to prevent patients from getting sicker and needing hospitalization,” said Jodi Meinke, NP, the director of Advanced Practice Provider Services for Spectrum Health who oversees the monoclonal antibody clinic

Nearly 900 patients have received the therapy at Spectrum Health since it became available in December.

That number includes 11 pediatric patients.

To be eligible for the treatment, Meinke said patients must meet certain criteria.

Pediatric patients must:

- Be 12 or older

- Weigh at least 88 pounds

- Test positive for COVID-19

- Have a symptom of COVID-19—and they must be within the first 10 days of symptoms.

They also must have a health condition that puts them at greater risk of severe illness from COVID-19.

The list includes but is not limited to the following conditions:

- Liver, cardiovascular, kidney disease

- Cancer

- High blood pressure

- Diabetes

- Asthma or lung disease

- Neurodevelopmental disorders

- A high level of immune suppression

- Stroke, cerebrovascular disease, seizures or other neurological condition

- Substance use disorder

- Obesity—for patients ages 12 to 17, that is body mass index equal to or greater than the 85th percentile for their age

- Other medical conditions and factors, including race and ethnicity, that could place an individual patient at high risk for progressing to severe COVID-19.

That’s a broad list that covers a wide range of conditions, and parents might find it difficult to determine if their child meets the criteria, Meinke said.

That is why she encourages parents to call the infusion clinic at 616.391.0351 if they have any questions. The medical team will provide information and guidance.

She also urged parents to have children tested for COVID-19 if they display symptoms of the illness—and to contact the infusion clinic as soon as possible.

“The earlier we can treat patients in the course of their illness, the more success we have in preventing progression of severe COVID-19 disease requiring hospitalization,” she said.

The spring surge in COVID-19 cases included a number of pediatric cases, and some of the children required extreme advanced life support, said Rosemary Olivero, MD, a pediatric infectious disease specialist.

“People have it set in their brain that children and teens don’t get severely ill from COVID-19, but we have seen a lot more pediatric hospitalizations,” she said.

She encouraged parents to consider monoclonal antibody therapy for children who are in one of the high-risk groups.

“Most of the people who get the infusion start to feel better in a day or so, which is so much quicker than it is for the majority of people who get this illness,” Dr. Olivero said.

Sense of smell returns

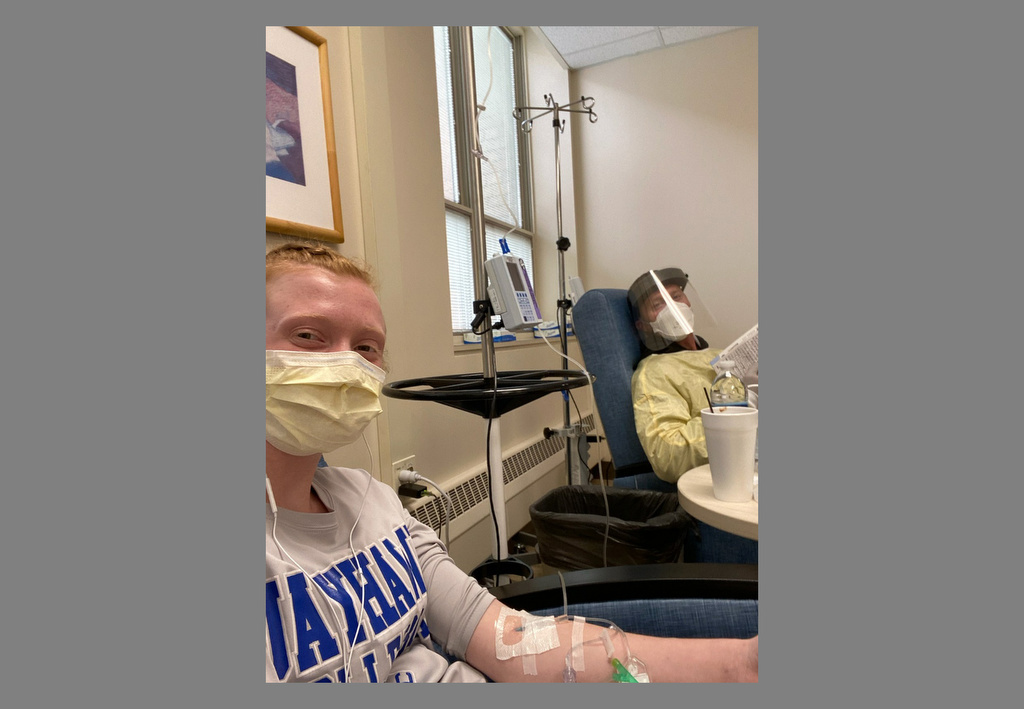

Tara’s dad, Steve Sweet, brought her to the clinic for her monoclonal antibody infusion.

“It was pretty quick,” she said. “I just sat in a chair and watched ‘Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs.’”

After the infusion, she waited an hour, drinking hot chocolate and eating graham crackers, as the medical team monitored her.

Tara felt no difference during the infusion or immediately afterward.

About a day and a half later, she started to feel better.

And at dinner time, she realized she could smell chicken cooking—her sense of smell had returned.

Within a few days, she no longer had shortness of breath when she climbed the stairs.

Now recovered, Tara has returned to school and sports. And she is glad she had the infusion.

“I think if I wouldn’t have done it, I would still have kept getting symptoms and they would have been worse,” she said. “Once I got the infusion pretty early on, it helped my body get back to normal and recover.”

Tara’s willingness to share her story does not surprise her mom.

“I think God uses Tara as a testimony in a lot of different ways,” she said. “Maybe this will help other kids.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

You are as brave as you are lovely Lady T. ; )