Landon Tiemeyer could shoot hoops, but he couldn’t run down the basketball court.

He could bat, but not race to first base.

He could walk the length of the boardwalk in Grand Haven, but only if he stopped several times to rest.

As long as 16-year-old Landon could remember, his heart pumped with enough power to keep him alive and enjoying life—but always set limits on how much he could do. If he pushed those limits, he turned breathless and blue.

Until this summer. Those limits are lifting now, thanks to a one-of-a-kind device made for Landon by a device manufacturer working with congenital heart specialists at Spectrum Health Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital.

And Landon is ready to tackle basketball courts, ball fields—and the game of life in general—with new gusto.

“It’s awesome,” he said, as he sat at his kitchen table in Wyoming, Michigan. “It’s exciting.”

“He is a completely new kid,” said his mother, Amber Tiemeyer. “He has more energy. He’s just brighter and happier. He seems to get more excited about things in life.

“He has a lot of life to make up for.”

‘Only half a heart’

It had been hard to imagine this day would come when Amber first learned Landon had a life-threatening congenital heart defect.

Everything seemed routine in her pregnancy with Landon, her third child, until her 20-week ultrasound. She watched and listened fearfully as specialists came in to review the scan and discuss her pregnancy.

“They said, ‘I’m sorry to tell you this, but your baby has only half a heart and probably will not survive birth. You need to prepare yourself,’” she recalled.

She learned Landon had hypoplastic left heart syndrome, a rare congenital heart defect in which the left side of his heart does not fully develop.

Reeling from the news, Amber and her husband, Steven, turned to prayer.

“Our prayer from the beginning was, ‘Whether this child lives one day or 100 years, we want his life to make a difference,” she said.

Landon arrived two months early, tiny and fragile—but alive. He spent 78 days in the neonatal intensive care unit before his parents could bring him home.

In his first years of life, Landon underwent a series of operations designed for babies with hypoplastic left heart syndrome, rerouting blood flow to ease the pressure on his heart and lungs.

But the last stage failed. His body rejected the new conduit connecting his vein and pulmonary artery.

Landon was only 3 1/2 years old and had already undergone six open-heart surgeries.

At that point, doctors told his parents “there is nothing more that can be done,” Amber said.

Let me tell you, my kid is dreaming now for the first time. This has truly, truly been an answer to a prayer that we did not expect.

Landon grew up, adapting to the limits placed on his activities. He learned that eventually his heart would not be able to keep up with his growing body. He would then be evaluated for a heart transplant.

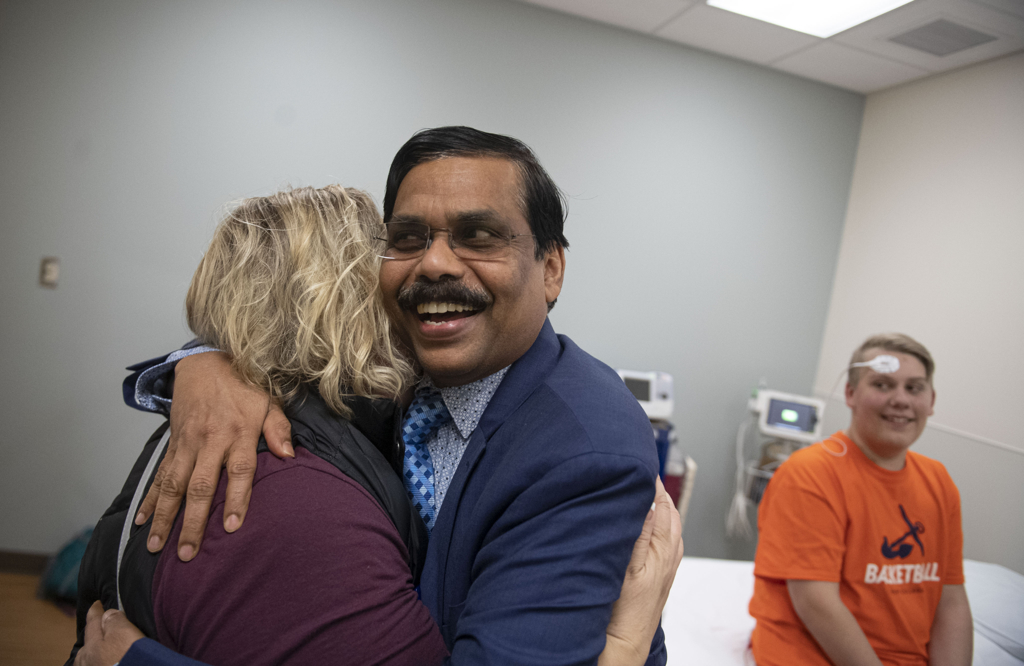

Around age 13, his parents took him to meet Joseph Vettukattil, MD, an interventional pediatric cardiologist and co-director of the Congenital Heart Center at Spectrum Health Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital.

Landon’s calm, reserved manner and easy smile impressed Dr. Vettukattil. But the doctor worried about what the future held for him. He had reached an age where a young person begins to think about the future—careers, a girlfriend, an independent life.

But Landon struggled even to climb a flight of stairs or walk across a parking lot. The oxygen saturation in his blood had dropped gradually over the years.

“You know behind that smile are a lot of worries,” Dr. Vettukattil said. “It’s cruel. For children like Landon, even the right to dream is taken away from them.”

He told Landon and his parents, “Let us assess his heart and see where we can take him from there.”

Exploring new options

A 3D echo and diagnostic cardiac catheterization revealed extremely high pressures in Landon’s heart. He gave him medications to reduce it.

Slowly, Landon showed signs of improvement. The oxygen level in his blood rose. Dr. Vettukattil performed a second heart catheterization, confirming that the medicines were indeed reducing the pressure in his heart.

He then moved forward, using data from a cardiac CT scan to print a 3D model of Landon’s heart. The congenital heart team, which encompasses surgeons, cardiologists and other specialists, explored Landon’s options.

They agreed open-heart surgery was not possible. The six surgeries he had as an infant and toddler had left adhesions—sections where tissue sticks together—that would raise the risk of bleeding and complications.

Dr. Vettukattil investigated ways to help Landon with a minimally invasive procedure.

He came up with a plan.

He would modify a stent similar to the one used in the surgical procedure that had failed when Landon was 3—to connect his pulmonary artery with the vein that brings blood from the lower parts of the body back to the heart.

But this unique stent would be implanted through a catheter placed in Landon’s vein.

Dr. Vettukattil explained to Landon and his parents that this would be an experimental procedure, one that would require authorization from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

Landon and his parents agreed to go ahead with it.

“If we don’t take chances, it doesn’t improve his life,” Amber said.

She told Dr. Vettukattil: “We are fully with you. Not only us, but our community—we are all with you. The God we believe in will strengthen you.”

‘The most exciting moment’

Dr. Vettukattil prepared extensively for the procedure.

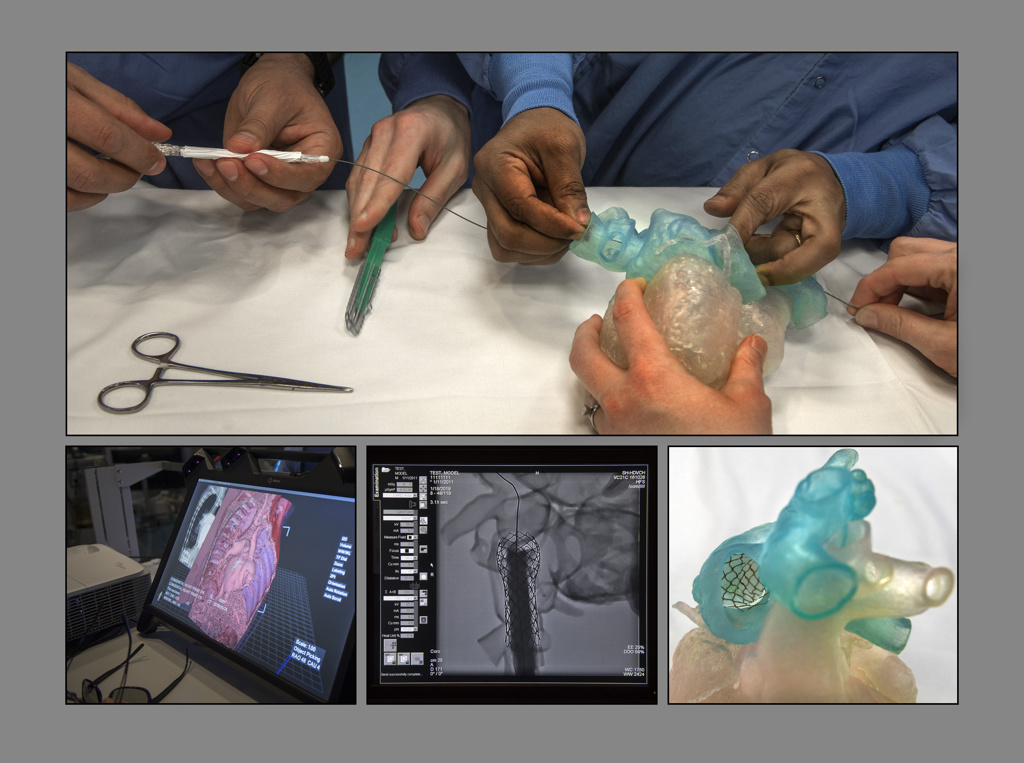

He had two copies of the stent manufactured by NuMed, Inc., of Hopkinton, New York. He practiced with one, placing it in the 3D printed model of Landon’s heart printed by Michigan State University College of Engineering’s Institute for Quantitative Health Science and Engineering.

As the balloon expanded inside the stent, Dr. Vettukattil watched carefully as the stent grew wider and shortened a bit. He wanted to make sure the dimensions were accurate and that it would not block crucial veins and arteries.

He performed a second test, using virtual reality.

The Congenital Heart Center specialists can visualize and plan interventions on complex heart defects using an advanced 3D imaging system called True3DViewer, created by EchoPixel of Santa Clara, California.

Wearing 3D glasses, Dr. Vettukattil looked at a virtual model of Landon’s heart on a screen, turning the image to view it from different angles. He implanted a virtual model of the stent into his heart.

This trial run confirmed the best placement for the stent and provided additional information to the heart team about how to deploy it.

The next step was the real deal: In a catheterization laboratory at Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital, he worked through a vein in Landon’s neck to deliver the stent to his heart.

The success of the procedure became clear even in the cath lab. Once the device was in place, the oxygen level in Landon’s blood rose.

“That was the most exciting moment,” Dr. Vettukattil said. “You could see the changes right away.”

Several weeks after the procedure, Landon returned to the congenital heart center for a stress echocardiogram. The oxygen level in his blood hovered in the 95 to 97 percent range. Before the procedure, it was in the low 70s.

But Landon didn’t need test results to know he was doing better.

In everyday activities, he felt stronger than ever. He had recently gone to a movie with friends and, for the first time, didn’t need the assistance of a parent or sibling. He walked the 1.5-mile boardwalk in Grand Haven with his brother—and didn’t stop once to rest.

Before the procedure, on the scale of 1 to 10, he would rate his life at a 4.

Now? He smiled.

“25,” he said.

Dreams—and softball

For his mom, Landon’s new enthusiasm for the future was the most profound change.

“Let me tell you, my kid is dreaming now for the first time,” she said. “This has truly, truly been an answer to a prayer that we did not expect.”

Six weeks after the operation, Landon played in the front yard with his dog Rex. His strength was continuing to grow. He had just played a basketball game where he ran up and down the court.

He couldn’t wait for softball season to start—this time, he would hit the ball and run the bases.

“Sometimes I just sit and watch him and I cry,” Amber said. “I never imagined in my life that this would be a possibility for him.

“Sometimes, it’s surreal still.”

For Landon, he sees life with his unique heart as a form of ministry. He wants to help others with congenital heart conditions.

“I think this is what God put me on Earth to do,” he said. “This is my purpose in life.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

Love this story! What a blessing.

Hi!! This story was not just a story for me! My 12 year old son lives this life daily as well! He also has hypoplastic left heart. His last surgery failed and we almost lost him! Now our last option is transplant! Your story brought me to tears to think there are options or other answers! He is the happiest boy and he is so limited as well. What I would do to meet this dr.!

Oh, we’re so glad we could fill your heart with hope, Kristina. You may reach the Congenital Heart Center and this team of specialists by calling 616.267.9150. Best wishes to you and your son!

Was such a great story hope he continues to live a good life. I thank god everyday for this chance to work at NuMed just knowing that these catheters will safe lives ❤️

That’s wonderful, Debbie, to know you work means so much to people like Landon and his family.