These are the sounds of victory for a child with a feeding disorder: A spoon scraping the bottom of a bowl of applesauce. A high five. And then—“Can I have some more?”

For 7-year-old Brianna Rondeau, polishing off a cup of applesauce marks a milestone in her struggle to overcome a disorder that left her unable to eat just about anything.

At one point, she refused all but pureed sweet potatoes and milk. And then she gave up milk, too.

Her parents’ quest for help led them to the Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital Intensive Feeding Program, a highly specialized program for children with feeding disorders. Her treatment included an eight-week session that runs five days a week.

Feeding problems are common in children—research shows they are the third most common concern parents report to their pediatricians. But for those who need intensive treatment, the problems go far beyond the typical “picky eater,” said psychologist Nancy Bandstra, PhD.

“We don’t see picky eaters here,” she said. “We see kids who medically or developmentally come from places that food and drink and mealtimes were negative and challenging, and we’re working through that.”

When Brianna arrived at the Intensive Feeding Program for a recent follow-up appointment, she quickly made herself at home in the waiting room while her parents met with her medical team.

A delicate girl with dark hair, she smiled and laughed as she grilled a toy hotdog in the play kitchen. She talked about life in second grade and what she wants to be when she grows up—a doctor, nurse and “bowling alley girl (professional bowler).”

Brianna lives in Bay City, Michigan, with her parents, Brad and Brandy, and her 3-year-old brother, Bryer.

Feeding challenges

The Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital Intensive Feeding Program addresses challenges that include:

- Total food refusal

- Dependency on a feeding tube

- Food tolerance difficulties

- Restricted eating patterns

- Difficulty transitioning to age-appropriate textures

- Recurrent vomiting

- Food allergies

These problems are often associated with one or more of the following medical or developmental conditions:

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)

- Failure to thrive

- Abdominal malformations

- Oral aversion

- Down syndrome

- GI dysmotility (example: constipation, delayed gastric emptying)

- Behavioral challenges

- Autism spectrum disorder

- Developmental delays/disabilities

Born a healthy baby, she didn’t appear to have problems eating until she started on the “stage 3” baby foods—soft, mushy foods with a bit of texture. When she ate baby spaghetti noodles and cereal puffs, she gagged and sometimes vomited, her parents said. They also noticed that she did not put items in her mouth to explore them, as other babies do.

Consulting with their doctor, the Rondeaus waited a bit to re-introduce new foods and hoped she would outgrow the problem. Eventually they took her to a speech therapist.

“We had her tested to see if there were any problems swallowing or chewing,” Brad said. “They said they didn’t see any issues with her oral motor skills.”

Slowly, Brianna accepted a wider range of pureed fruits and vegetable, as well as infant oatmeal and rice cereal. She ate mashed potatoes and macaroni and cheese a few times.

But over time, a growing number of items moved to the “No” list. By age 4, she was down to a few types of food— milk, baby cereal and a few orange baby foods like peaches and sweet potatoes.

In the fall of 2013, at age 5, she became ill with a virus and refused all food and drink. She had to be hospitalized for dehydration. It was the first of three hospitalizations for dehydration and refusal to eat while sick.

As they sought help from experts statewide, the Rondeaus discovered the Intensive Feeding Program at Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital. Staff members say it is the only program in Michigan and one of 15 to 20 nationwide that provide such specialized care through a multi-week program.

In the summer of 2015, she took part in the eight-week program. She and her family stayed at the Ronald McDonald House of West Michigan, so Brianna could receive three therapeutic meals a day, Monday through Friday, at the clinic.

A cycle develops

The Intensive Feeding Program brings together a team of experts—a neurodevelopmental pediatrician, nurse practitioner, psychologist, dietitian, occupational therapists, speech and language pathologists, a medical social worker, a child life specialist and a culinary technician.

For most of the young patients, a medical condition lies behind their feeding disorder, said Lynn Fagerman, NP. Some were born premature. Some had bad reflux as infants and learned to associate food with discomfort.

Although she is not certain of the cause of Brianna’s issues with food, she noted that Brianna had reflux and that she does not like the feel of foods in her mouth. Like many children with feeding disorders, she has anxiety about eating and severe texture aversions.

“Kids develop a whole number of strategies that very effectively get parents to back off,” Bandstra said.

They learn that if they cough, gag or vomit, the food that makes them uncomfortable will go away. While that reduces anxiety in the short run, it does not help them develop new skills.

Fagerman sympathizes with parents who struggle to cope with a child’s aversion to food.

“It’s hard work and it tugs at your heartstrings,” she said. “It’s very stressful for the kids and the parents.”

‘We challenge them incrementally’

Therapists tailor their treatment approach to each child’s needs. First, they build rapport and trust with the child. They work with children to open their mouths on request and to accept a dry spoon.

“We may not introduce food or drink substance until weeks into therapy because we need to establish those precursors to food and drink intake,” Bandstra said. “We are developing a new association of, ‘I can do this. I have to do this.’ And we challenge them incrementally from there.”

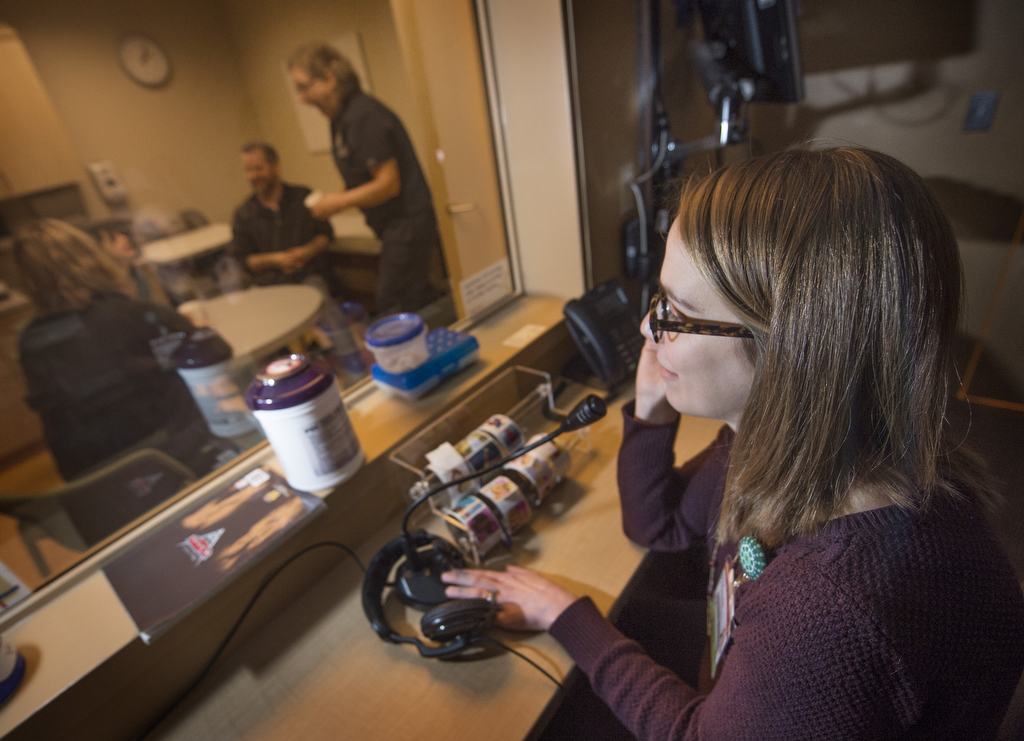

At first, the therapists work with the child while parents watch from behind a one-way mirror.

The Rondeaus marveled as they saw Brianna eat pureed pears and other foods she had long refused.

“We were almost in tears because she was eating something different,” Brad said.

Therapy also included anxiety management strategies, such as breathing exercises and positive self-talk. Brianna’s success with bites and drinks was reinforced with fun activities—such as bubbles, games and snippets of a movie.

Eventually, the Rondeaus were trained in Brianna’s feeding protocol. As they worked with Brianna, they wore an earpiece and received feedback from a therapist watching from behind the one-way mirror.

Five weeks into the summer program, Brianna suffered a setback. On a trip home for the weekend, she refused to eat the items she had readily eaten at the clinic. She was admitted to the hospital and received a feeding tube through her nose as well as an IV for fluids. The team from the Intensive Feeding Program worked with her in the hospital until she resumed eating.

After the intensive program wrapped up, the Rondeaus followed the same feeding practices with Brianna at home.

Physical and social effects

A feeding disorder affects more than a child’s nutrition and growth. As a psychologist, Bandstra is particularly concerned on its impact on quality of life. Anxiety about eating can interfere with a child’s participation in social events—including school lunches.

“There are a lot of missed opportunities socially, especially at the school age, with kids who have issues with eating,” she said.

At the clinic, the medical team tracks every bite and drink taken by every child at every meal. The information goes into a clinical database also used in research by members of the Intensive Feeding Program research team. These research findings are presented at conferences to help others working with children with feeding disorders.

They hope to address the gap in research about feeding disorders.

“I don’t think what we are doing is mind-blowing, but it hasn’t been disseminated to the literature or the community as you think it would be,” Bandstra said.

A good prognosis

When Brianna returned for a follow-up visit recently, Fagerman noted she had gained 4 pounds in two months—adding to the 6 pounds she gained during the program.

She advised the Rondeaus to add a new entrée and another vegetable to Brianna’s menu options. All the foods are pureed. At a future visit, they will introduce foods with some texture.

Given a cup of applesauce, Brianna sniffed it and asked questions. Who made it? Was it the same kind she had before? She giggled, but her reluctance to eat reflected anxiety, Bandstra said.

Soon, Brianna took a little bite, and then quickly ate all of the applesauce, scraping the bottom of the bowl to get the last bit. Mom and Dad gave her high-fives.

“She’s a really good eater once she gets past that barrier,” Bandstra said.

She is optimistic about Brianna’s ability to overcome her feeding disorder.

“I think her prognosis is really good,” she said. “She demonstrated the need for that transdisciplinary approach, but with it, she was able to be successful. And her parents were able to take it home and maintain it. And that is key.”

Brianna’s parents were impressed by her willingness to work with the program. The progress she made has spilled over into other areas of her life.

“She is so much more confident in herself,” Brad said. “She is more willing to try new things.”

“It’s been pretty amazing,” Brandy said. “She has done a great job.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

What a huge victory Brianna!! Your story was very inspiring, thank you!