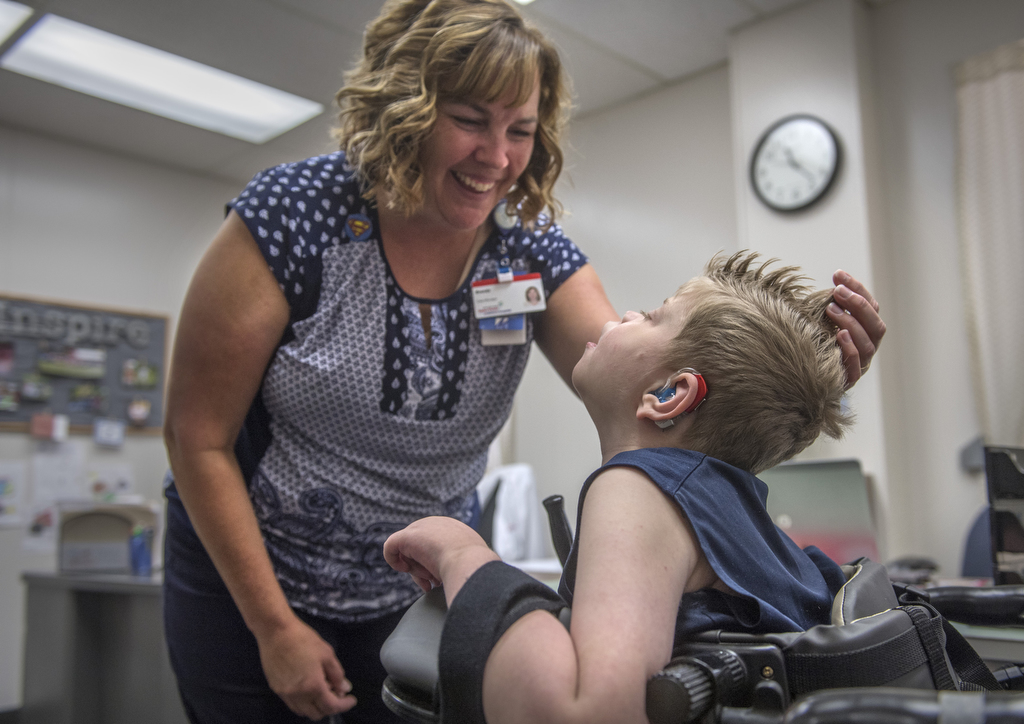

It’s 11 a.m. on a Tuesday, and Vie Adams has medications ready to go for 9-year-old student Shane Durfee.

As the Spectrum Health LPN gives Shane his medications and feeds him Pediasure through his G-tube, she gently strokes his hand.

It’s no secret among the Seiter Education Center staff that Adams is Shane’s “favorite.”

“I mention Vie and he just lights up,” said Shane’s mother, Michelle Baylor.

Adams is one member of the Spectrum Health nursing staff who works on-site at the school, which houses 50 special needs students ages 3 to 26, including some like Shane with complex medical needs.

She’s joined by Brenda Bartula, RN, and another LPN, Christie Bilski. Having nurses at the school is possible thanks to a partnership that started four years ago between the Montcalm Area Intermediate School District and the Spectrum Health Healthier Communities School Health Program.

For decades, the district employed a nurse at the Greenville, Michigan, school. But after she retired, the school system reached out to Spectrum Health for help.

“The teachers and paraprofessionals were doing the health things all day long,” said Tracy Zamarron, director of school health programs for Healthier Communities. “They didn’t have the opportunity to truly just teach.”

Now teachers concentrate on education and leave the medical care to the nurses. Having a medical presence is the reason many Seiter students can even come to school, according to Teresa Boyer, the school district’s special education supervisor for early childhood and students with cognitive impairments.

“They have the same belief system we do, that all students can learn,” she said. “How does it get any better than that?”

Baylor said knowing the nurses and teachers are looking after Shane gives her less anxiety about sending her son off to school.

Shane was born with three rare chromosomal abnormalities—chromosome 18q deletion, Pitt–Hopkins syndrome (an abnormality of chromosome 18 and the TCF4 gene) and a partial duplication of 18p. As a result, he suffers from seizures, poor muscle tone, blindness, deafness and cognitive impairments.

“They told me he wouldn’t live through the week when he was born, and now he’s 9,” Baylor said.

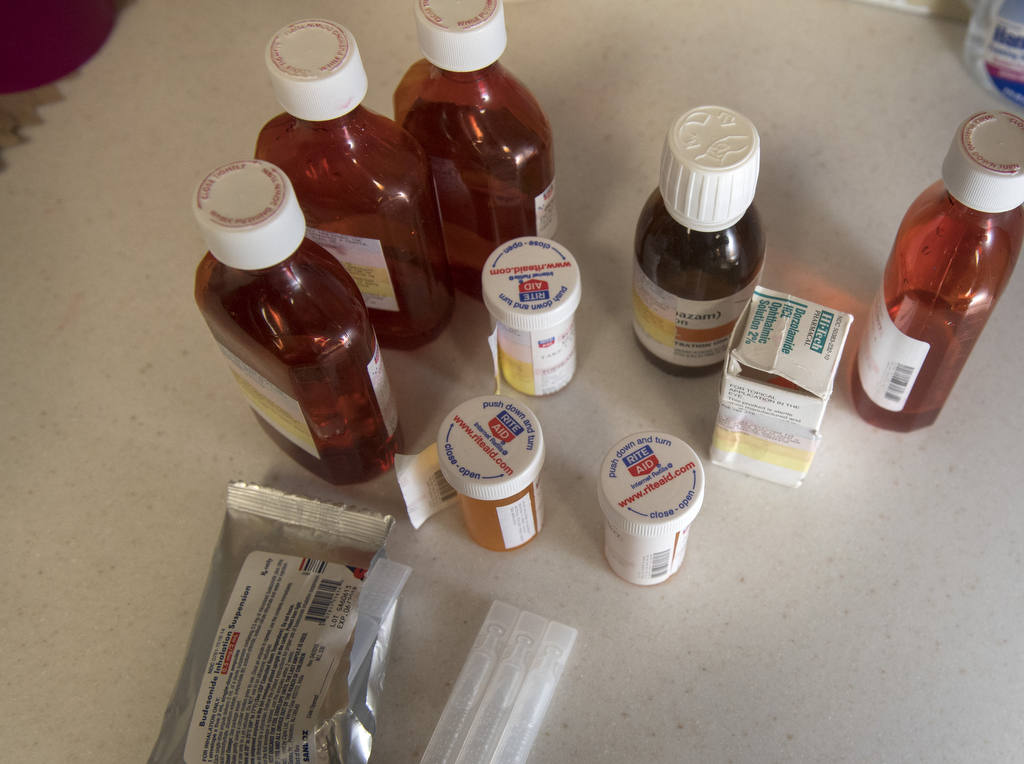

Shane requires nine medications at 11 a.m. every day from the nurses at school, and then Baylor repeats them at 11 p.m. at home. At school, the nurses store the medications in a locked box in the classroom, so they can give them to students without removing them from the classroom.

Shane’s teacher, Heather Keur, found relief in having nurses at the school, since she was used to doing everything herself.

“Now that I look back on it, I don’t know how I fit it in,” Keur said of administering medications and feedings. “Now, I can teach. It’s really helped us out a lot.”

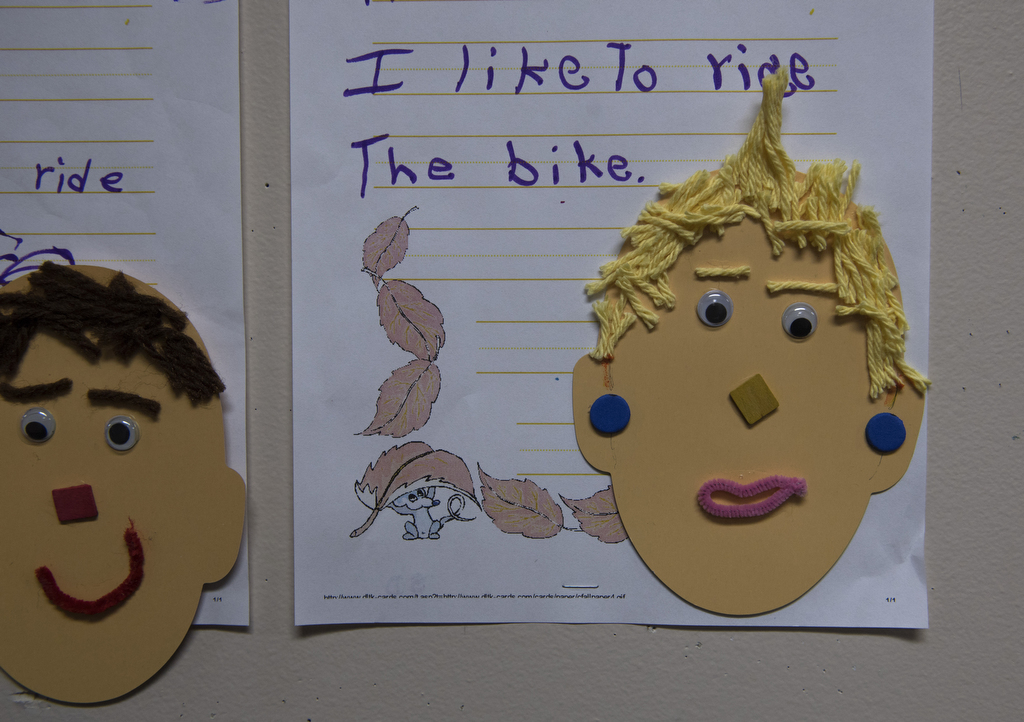

Keur takes great joy in seeing the gains students like Shane have made at school. When he started at Seiter at age 3, he couldn’t walk, and now he walks on his own with a device called a pacer, holds his head up, sits on his own and uses purposeful touch.

“I love my job. I really believe that children with special needs get undersold. They are so misunderstood,” Keur said. “There are brains in these bodies that cannot communicate. We bring that brain out.”

Bartula, as the registered nurse in charge of health needs in the district, not only oversees Seiter Education Center, but also 12 additional classrooms throughout the county. If she cannot be there, she uses video visits through the Spectrum Health app to chat with teachers. She’s in charge of health care plans for students who require them, as well as health education and staff training. She also often sits in on meetings with teachers and parents to discuss students’ individual education plans.

Spectrum Health has various types of nursing arrangements with other school systems throughout West Michigan. Teachers and students might consult with a nurse on site, by phone or through the Spectrum Health app.

Regardless of their format, Zamarron said, the programs are designed to improve educational outcomes by using health care as a tool to keep kids healthy and safe in the classroom.

Bartula, who formerly worked in the neonatal and pediatric intensive care units at Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital, said she loves working with students, parents and teachers.

As she talked with Baylor about Shane, she said, “You make my job easier because you let me know how you want Shane to be taken care of. We are an extension of the home.”

Baylor said trust has developed with Bartula and the other nurses. And she admits trust is not easily given because of the trials the family has endured. She calls Shane a superhero and sometimes dresses him in Superman clothes.

“You don’t go through the stuff that he has been through without being a superhero,” Baylor said.

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

What an aspiring article. Keep smiling sweet Shane!