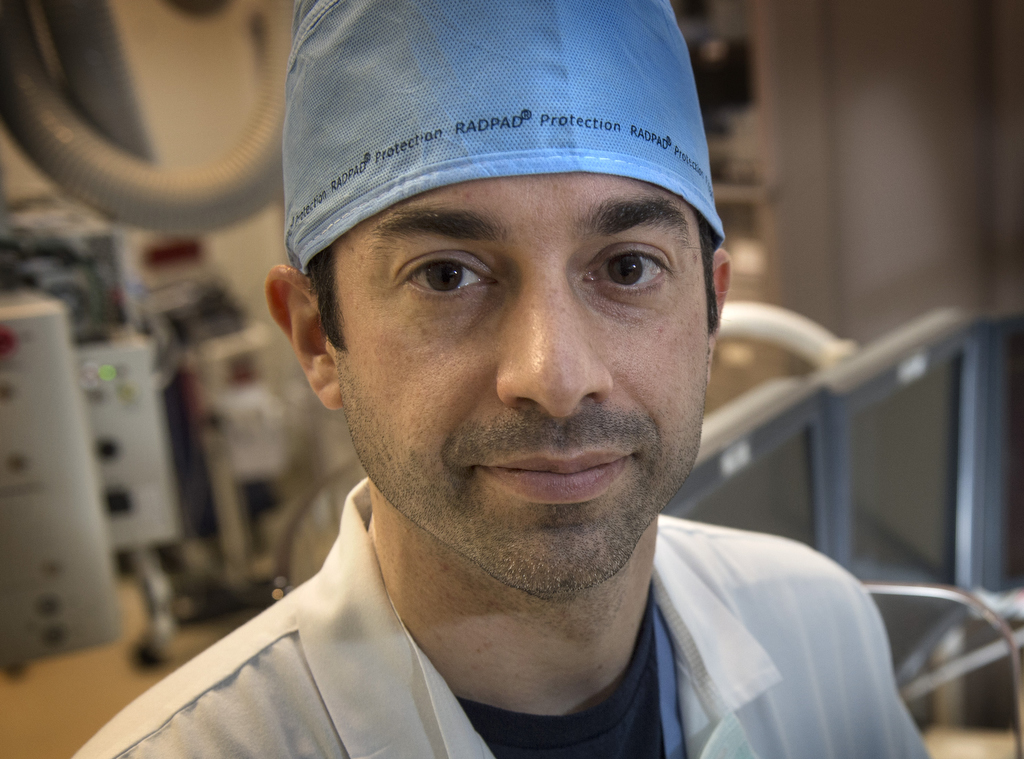

Ryan Madder, MD, maneuvered a joystick and watched on a monitor as he moved a stent through a patient’s artery.

“It’s much simpler than playing Xbox with my kids,” he said, sitting in a cockpit several feet from the patient at the Spectrum Health Fred and Lena Meijer Heart Center.

The robotic system may resemble a video game, but its value goes beyond fun and games. It delivers benefits for patients with greater precision in navigating arteries, and for physicians with reduced radiation exposure, he said.

The system, created by Corindus Vascular Robotics, is one area of focus for Dr. Madder’s research into making heart catheterization procedures more effective and safer for everyone in the cath lab.

He used the device recently to perform a heart catheterization on Ula Calsbeek, a 75-year-old woman from Grand Rapids, Michigan.

Calsbeek came to Meijer Heart Center after she noticed tightness in her chest when she took her daily walks. After an EKG and a stress test showed problems, her doctor referred her to Dr. Madder, an interventional cardiologist.

On the monitor in the operating room, an image showed the cause of Calsbeek’s discomfort: two pinched spots in the left anterior descending artery.

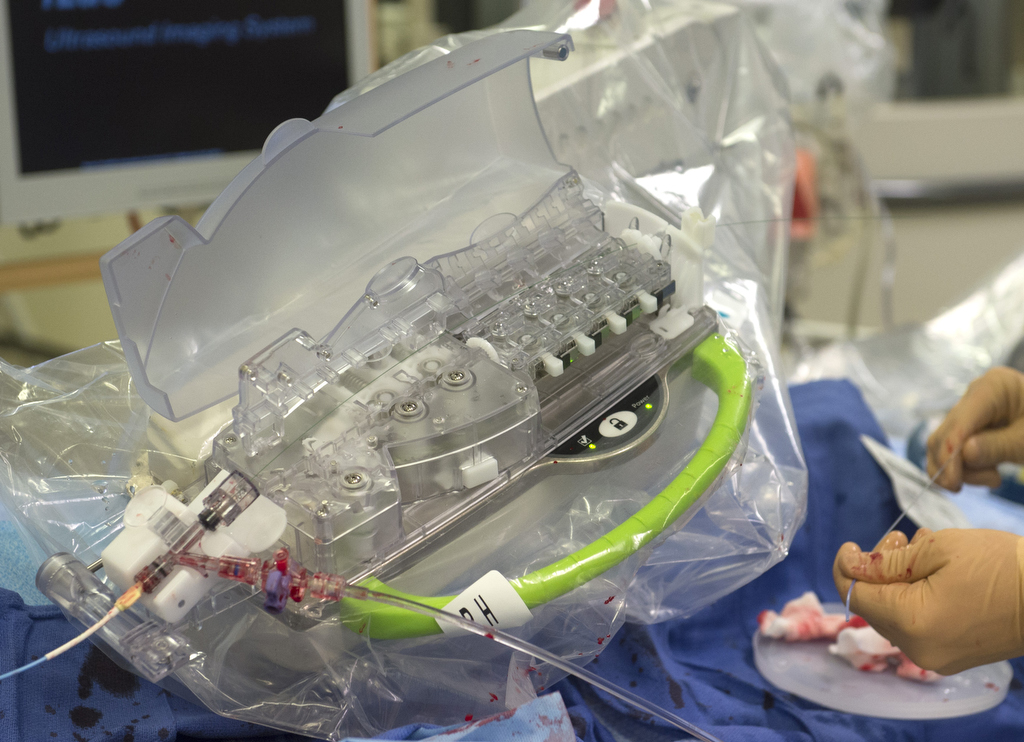

Madder fed a slender wire into her right wrist and up the artery. From the cockpit several feet away, he operated the robotic arm that controlled the catheter’s progress.

In each blockage, he placed a balloon, which inflated to push back the plaque. Then, he placed a stent to hold open the passage.

“Everything is done with these two joysticks,” he said, gesturing to the white knobs on the control panel.

The robotic precision helps the cardiologist measure the lesions, determine the size of the stent needed and place the stents in the right spot.

“We think manually we can move things millimeter by millimeter with our fingers,” Dr. Madder said. “Whether we can do that or not I don’t think is really known.

“With this, you can actually push a button and move it millimeter by millimeter, forward and back.”

A clear shield surrounds the Corindus cockpit, protecting the cardiologist from the radiation used to create X-ray images throughout the procedure.

Minimizing risks

Researchers have raised the alarm in recent years about health risks for interventional cardiologists and radiologists—because of the radiation exposure involved in doing multiple procedures and from wearing lead aprons weighing 15 to 20 pounds.

Reports have documented orthopedic injuries, particularly to the neck and back, as well as cancer risks. A study of head and neck tumors in interventional cardiologists and radiologists found 86 percent occurred on the left side of the head—which receives greater radiation exposure during procedures. In the general population, tumors are divided 50-50 on the left and right sides.

“My generation has just taken this as part of the hazard of the job,” said David Wohns, MD, 61, the medical director of the Cardiac Catheterization Laboratory at the Meijer Heart Center. “And frankly, until the last five to 10 years, we did not recognize the lifetime risk in terms of orthopedic injuries and radiation-induced cancers.

“We are now laser-focused on making this as safe for the provider as we can.”

Dr. Wohns, and Dr. Madder, 38, recently took part in a clinical trial using the Corindus CorPath System. The trial led to approval by the Food and Drug Administration to use the system for radial—or wrist—access.

All in the wrist

Cardiologists increasingly are accessing the heart arteries through the wrist, rather than through the groin, Dr. Wohns said.

“In the United States, about 40 percent of interventions are done radially,” he said.

He and Dr. Madder use that approach for most heart catheterizations they perform. The procedure has fewer complications, he said, and patients are able to sit up right after surgery instead of lying flat for two to three hours.

In most cases, physicians use the right wrist. But sometimes they must use the left, because of prior surgeries or other complications. And those procedures are more difficult to do, given the set-up of the operating room.

“They are longer cases and involve more radiation,” Dr. Wohns said. “When they are done robotically, it can eliminate the additional radiation that occurs.”

‘Painless’

After placing the stents, Dr. Madder returned to Calsbeek’s side. He wore a “Zero Gravity” suit—a lead garment suspended from above, which protects against radiation but does not cause wear and tear on the joints.

“We got a great result,” he said.

Calsbeek was propped up in the bed and wheeled into recovery. Later, meeting with Dr. Madder, she said the procedure was “painless.”

She asked if the robotic system he used had a name.

“No, it doesn’t have a name,” he said.

‘It needs a name,” she said.

What’s next

During the procedure, Dr. Madder and all the operating room staff wore badges measuring radiation exposure. He collects the data for research into ways to eliminate exposure for everyone involved.

When he did his fellowship in cardiology, Dr. Madder said he couldn’t imagine that one day he would use the robotic system to place a stent. And he didn’t realize his days playing Nintendo would prepare him for it.

“I didn’t see this coming,” he said. “Which makes me excited about what other things are on the horizon that I don’t know about yet.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

Good Information…

Fantastic program…

procedures of the future available now because of a few dedicated individuals focused on better care for their patients…

Congratulations! All those exciting and laborious research hours opening doors of endless opportunities for superior healthcare.

Thanks, Mimi! The miracle of modern medicine never ceases to amaze me. 🙂