As soon as 15-year-old Lilly Gordon walks into her front yard, a scruffy barn cat named Boo greets her with a knowing look.

The feline’s furry gaze always suggests he knows something: From this human, she’s guaranteed some long-lasting affection.

Lilly became Boo’s favorite person after her friends rescued him from between two fences and she nursed him back to life. They’ve been pals ever since.

It’s not surprising.

Lilly has a soft heart. She’s soft-spoken, but also strong and courageous.

She lives with cystic fibrosis, an inherited disease that causes thick mucus to gather in her lungs and digestive tract.

Instead of letting the disease stop her, she has developed into a typical, active high school sophomore.

Too good to be true?

Most of the staff and students at Lakeview High in Battle Creek, Michigan, don’t see anything unusual about Lilly.

But her story could have been much different had she been born decades earlier. Thanks to new treatment options, the life expectancy for those with cystic fibrosis is on the rise.

Lilly became part of that change as a child, when she participated in a clinical trial for an experimental drug.

As a baby, she would fuss and cry for hours after eating, said her mom, Mindy Gordon.

“I just knew something was kind of off,” Mindy said. “The pediatrician told me I was being a paranoid first-time mom.”

When Lilly turned 8 months old, the family switched doctors. Within a week, the new doctor used a sweat chloride test to diagnose her with cystic fibrosis.

“I had to look it up because I had no idea what it was,” Mindy said.

Soon after the diagnosis, Lilly began treatment at the Cystic Fibrosis Clinic at Spectrum Health Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital.

At age 7, Lilly got an invitation to participate in a double-blind trial of a then-new drug, Kalydeco, which was directed by Susan Millard, MD, chief of Pediatric Pulmonary and Sleep Medicine at Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration later approved the drug as a cystic fibrosis medication.

“I wrestled with it,” Mindy said. “I didn’t want her to be a guinea pig.”

Researchers divided the trial participants into two groups: One group received a placebo, the other received medication.

Within months, Lilly saw improvements.

Her skin didn’t have the strong, salty taste of a child with cystic fibrosis. The dryness and cracking between her toes disappeared. She coughed less.

It seemed too good to be true.

“When she was on the drug it changed everything,” Mindy said. “We’re very thankful for it. I don’t know what her health would be like if she wasn’t on it.”

Ever-vigilant

Kalydeco is one of many treatments used in the Cystic Fibrosis Clinic.

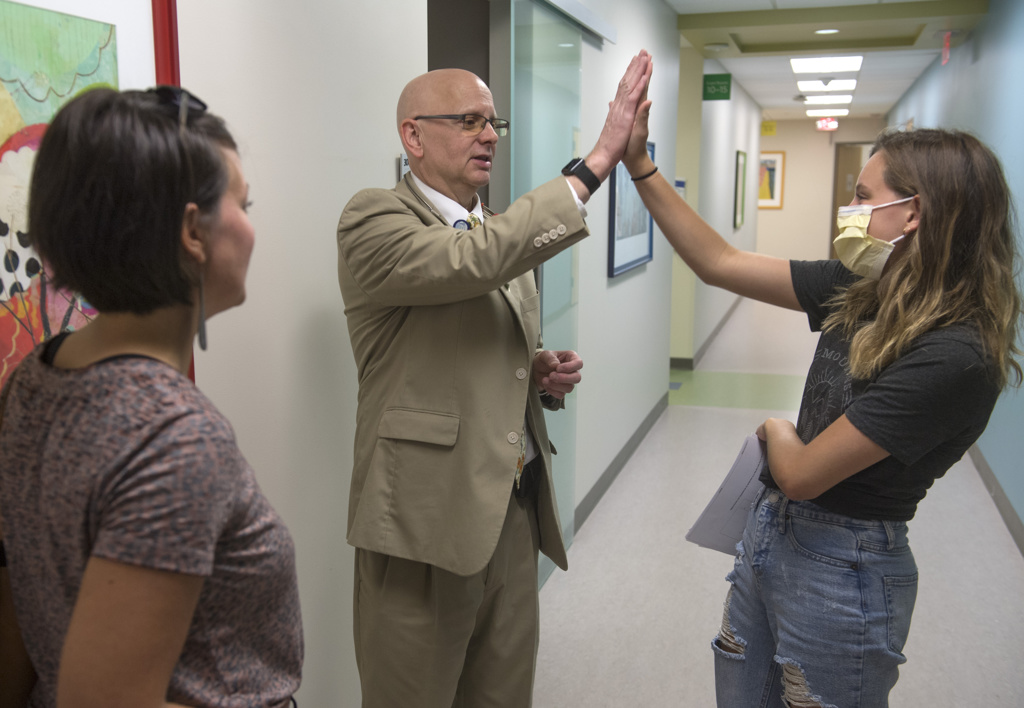

The clinic’s patients are seen four times a year, allowing doctors to monitor for small problems before anything becomes a significant issue, said John Schuen, MD, a pediatric pulmonologist at Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital.

Today, all newborns are screened for cystic fibrosis. This allows treatment to begin right away.

“Now CF is no longer considered a fatal illness in childhood,” Dr. Schuen said. “The sky is the limit. We won’t know for a decade or two, but our goal is for our kids to be grandparents and outlive their parents. This is a time for tremendous hope.”

Living with cystic fibrosis, Lilly must be more responsible and vigilant than other teens.

Her day begins and ends with an oscillating vest that vibrates her lungs to loosen and thin any mucus. This helps her remove bacteria and avoid infection.

She takes Kalydeco twice a day. This opens the chloride channels to keep the lining of her lungs healthy.

She also uses a nebulizer for breathing treatments and takes enzyme replacement pills to improve digestion before every snack and meal.

“It’s hard to do my treatment every morning and every night,” she said. “I have to wake up a half hour earlier, so that’s tough. Other than that, I live my normal life.”

She has become a standout athlete on the track team. Her times in the 200-meter and 400-meter runs qualified her to run with the varsity team last spring—as a freshman.

When practices get tough, she doesn’t bring up her illness.

Instead, she just works harder to meet the coach’s expectations.

“She doesn’t let anything stop her,” Mindy said.

Writing her own script

Over the summer, Lilly and her friends were fascinated by the movie “Five Feet Apart,” a teen romance that highlights cross-infection, one of the imminent dangers of her disease.

That’s why she has never met any others with the same disease face-to-face.

“I follow a couple of girls on Instagram who are my age and have it,” Lilly said. “The rule is you have to stay 6 feet apart. No hugging. No physical contact.”

“It can feel like a lonely disease sometimes,” Mindy added. “Social media can help.”

Mindy has been quick to reassure her daughter that her fate won’t follow a movie storyline.

“How fortunate we are to have this drug,” she said. “Dr. Schuen says you have rock star lungs, they sound amazing.”

Like many her age, Lilly has yet to iron out the details in her college plans and career aspirations.

But her compassion and determination—and modern treatment options—are sure to carry her through.

“CF doesn’t define me,” Lilly said. “I just live a normal life and it’s just a part of it. It doesn’t define my life.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

It was a pleasure working with the Gordon family on the Kalydeco clinical trial. Thank you for taking the chance at a time where there was no approved medication to treat the root cause of CF.

Wow, this is so enlightening! Great news for Ms. Gordon and the rest of the CF community. I had always thought the prognosis was poor. I’m glad to hear that’s not the case anymore. Thank you Dr. Millard!