Kortney Davis looks back on Christmas 2011 as one of the hardest days of her life.

Her 10-day-old daughter, Karlee, lay in the NICU in the Gerber Foundation Neonatal Center at Helen DeVos Children’s Hospital, fighting for her life. Meanwhile, her 19-month-old son waited at home with his dad and grandparents.

As she made the 100-mile round trip to the hospital and back that holiday, Kortney could only think, “I’m supposed to have two kids at home right now.”

At that moment, no one knew whether Karlee would pull through.

‘Giant gastroschisis’

Karlee was born with an extremely rare form of gastroschisis, a birth defect in which a developing baby’s intestines slip through a hole in the abdominal wall and grow outside the body within the amniotic sac.

In Karlee’s case, more than her intestines had escaped her body—her liver, spleen and bladder had, too.

This was “something none of us have ever seen before,” said James DeCou, MD, Karlee’s pediatric surgeon. “We called it a giant gastroschisis—we didn’t have a name for this.”

Repairing a standard gastroschisis is usually a straightforward process. Immediately after birth, a pediatric surgeon places the infant’s intestines inside a plastic bag called a silo and secures the silo inside the hole in the belly. Over the next few days, the doctor gradually pushes the intestines into the abdominal cavity.

Typically, the hole in the abdominal wall can be surgically closed within the first week, Dr. DeCou said, “and the vast majority of babies with gastroschisis do very well.”

But with Karlee’s situation, all bets were off.

Dr. DeCou and his surgical colleagues searched the medical literature and could find only three other patients in the world who’d had gastroschisis with the liver out.

“All of them died from it,” he said. “To the best of our knowledge, she’s the only person who has ever survived this.”

That’s why he calls her “the famous Karlee Davis.”

‘Uncharted territory’

An ultrasound halfway through Kortney’s pregnancy revealed the gastroschisis. Because this made her pregnancy high risk, she began seeing a maternal fetal medicine specialist at Spectrum Health.

At every prenatal visit, she would hear that the hole had grown. By 28 weeks, doctors confirmed her baby’s liver and spleen were outside her body.

At 33 weeks, Kortney learned her baby might be experiencing congestive heart failure. Though this turned out not to be the case, Kortney struggled with the realization that “my chances of walking out of the hospital with a baby were probably slim to none.”

At 36 weeks, her water broke and she underwent an emergency cesarean section. A neonatal team stood by in the delivery room, ready to whisk Karlee away to the operating room.

“I didn’t really see her until the following morning—and that was after her first surgery,” Kortney said.

It wasn’t a pretty sight. Besides the silo over her belly, Karlee had IVs, wires and tape everywhere.

From that day on, Dr. DeCou visited Karlee in the NICU daily.

“The big picture was clear: We needed to get everything inside and get things closed,” he said. “How to do that? I mean, this was sort of uncharted territory.”

When Karlee turned 4 days old, Dr. DeCou replaced her original silo bag with an extra-large, special-order version that would better accommodate her gastroschisis.

Over the next 10 days, he gently pressed parts of the organs further inside Karlee’s body. But he knew the liver wouldn’t go in.

“The problem with the liver was that it didn’t have its normal shape,” the doctor said. Because it had formed outside Karlee’s body, her liver had taken on a spherical shape that didn’t fit the spot where it belonged.

“If you try to push it in too fast … you can have blood flow problems, and that’s probably why previous patients didn’t survive with this,” Dr. DeCou said.

Karlee needed time. As her feedings increased and her body grew, her abdomen would make room for her liver.

In the meantime, Dr. DeCou wanted to seal up her abdominal cavity, even with half her organs still waiting outside. Dr. DeCou removed the silo bag and sewed a large collagen patch onto Karlee’s belly—big enough to cover the bulge of organs.

Over time, as things slipped inside, he reduced the size of the patch.

It wasn’t until Karlee reached 4 months old that her liver would slide in. It happened during an office visit with Dr. DeCou.

“I remember the day the liver went in, because it went ‘Bloop.’ And it’s like, ‘Hey, liver’s in. How’s she doing? She’s doing fine. OK, good,’” Dr. DeCou said.

“That was a milestone.”

By that time, Karlee had been living at home, having graduating from the NICU after 74 days.

Earning that hospital release proved to be another challenge.

First she had to be weaned off her strongest pain medications. Then, like every NICU baby, Karlee had to pass a car seat test. Because she had the large, vulnerable hump on her belly, the hospital staff created a plastic turtle shell to protect her abdomen during car rides.

But each time a nurse strapped her into her car seat, her vitals plummeted. No matter how hard her team tried, Karlee couldn’t pass the test.

So Dr. DeCou’s office ordered a specialty infant car bed for Karlee, which allowed her to lie on her side while strapped in for safety.

Cleared for travel, Karlee had frequent outpatient appointments. Once all her organs had settled inside her, Dr. DeCou removed the remainder of the collagen patch.

By the time she hit 6 months, her skin had fully healed over, with all her organs safely inside.

‘She’s delightful’

As she grew, two new issues arose: a problem with the position of her diaphragm and a ventral hernia that needed to be repaired.

In each case, Dr. DeCou fixed her up, bringing the number of surgeries he’s performed on Karlee to 16, the last one when she reached 17 months old.

Given their history together, Kortney can’t imagine anyone else operating on Karlee.

“He knows everything about her,” she said.

And he’s earned the family’s trust.

“He never gave me false hope, never made it seem like it was going to be easy,” she said. “But he never was negative either. He always said, ‘Hey, we’re going to get this. It’s going to take me a little longer because I don’t know what we’re going to encounter once we get in there, but … we’ve got this.’”

After everything she’s been through, Karlee, now 7, is understandably leery of medical staff in blue uniforms.

“It’s still very real to her, even though some of her worst surgeries she was too young to remember,” Kortney said. “I know it’s been hard on her.”

And yet, on the whole, Karlee is doing great.

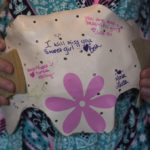

She’s a bright, outgoing, energetic girl who loves playing with dolls and engaging with her siblings and grandparents.

On a May afternoon, she sang and danced around the living room of her family’s home in Nashville, Michigan, pleased to show off her new costume for a spring dance recital.

She flipped through a stack of pictures of herself as a baby, amused to see how small and cute she had been.

“She’s delightful,” Dr. DeCou said. “And she’s doing so amazingly well.”

Karlee, he said, is proof that “even things that were not thought to be survivable are survivable sometimes.”

His assessment aligns well with what’s become a motto in the Davis house: “You never know how strong you are until being strong is the only choice you have.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

I read about so many big and small miracles at Spectrum Health every week on Health Beat, but this is a great BIG miracle … WOW what an amazing story!

Thanks, Brion!

Wow! Inspiring story. God bless this beautiful child and her family. And Thank God for her surgeon!!!

I can relate to this family. Our son had a massive omphalocele at birth and has spent much of his life in the hospital. ALL of his organs were outside of his body and he had no skin from all around his ribcage to his rectum. He has had 104 surgeries to date and continues to receive care and live his best life possible with amazing kindness towards others, courage and strength. I am so grateful Karlee is doing amazing and is living her best life. Thank God for our doctors, nurses and medical staff.

So glad to hear your son is doing well and living his best life possible. Sending you and your family all the best, Kathryn.

It just goes to show how having faith and trusting in God…makes all the difference in the world! I thank God for the doctors and his entire team and their patience!