Parkinson’s disease has a way of making people smaller. Movements shrink. Feet shuffle. Voices dim.

Joyce Ossewaarde does not plan to slip quietly into that mode.

The 82-year-old great-grandmother is going big and getting loud―aided by a Spectrum Health rehab program developed specifically for Parkinson’s patients.

The intensive program, aptly named Big and Loud, helps people as they move, speak and function in their daily lives, even as their disease progresses.

“It’s a big deal. It is life-changing for them,” said speech therapist Lea Norbotten, SLP. “When they start to get their voice back or their movements back, they get themselves back.”

And in Ossewaarde’s case, a few more strikes and spares. She bowled a 186-game recently, her first in years.

“I think this is a wonderful program,” she said, just before she began her last session. “I hope it keeps me where I am.”

“Joyce has done fantastic,” Norbotten said. “Major, major improvements.”

The dopamine effect

Spectrum Health therapists began three years ago to work with Parkinson’s patients using the Big and Loud approach. The therapists underwent training and were certified by the international program, LSVT Global.

The intensive four-week program provides therapy four days a week. Speech, physical and occupational therapists lead patients in exercises to counteract the effects of the degenerative neurological disease.

The capacity is there (to push back against debilitating symptoms). That’s one of the most exciting things that I’ve seen. They realize they can move better than they thought they could.

There are about 1.2 million Americans living with Parkinson’s disease and 60,000 new cases diagnosed every year in the United States. Parkinson’s, a slowly progressing disease, can cause tremors, muscle stiffness, slow movement and impaired balance. Patients gradually lose the brain cells that produce dopamine, a substance needed for smooth muscle movements.

“Their movements get smaller and their movements get slower,” said occupational therapist Kerri Vryhof, OT. “What feels like normal movements to them come out as very small.”

They start to shuffle their feet, rather than walk. Their shoulders may slump forward. Their smooth-flowing cursive might shrink to a tiny, cramped script.

The loss of dopamine takes a toll on the muscles involved in speech, too. Patients can lose volume and clarity.

“Their speech can become monotone,” Norbotten said. “There is no inflection or enthusiasm.”

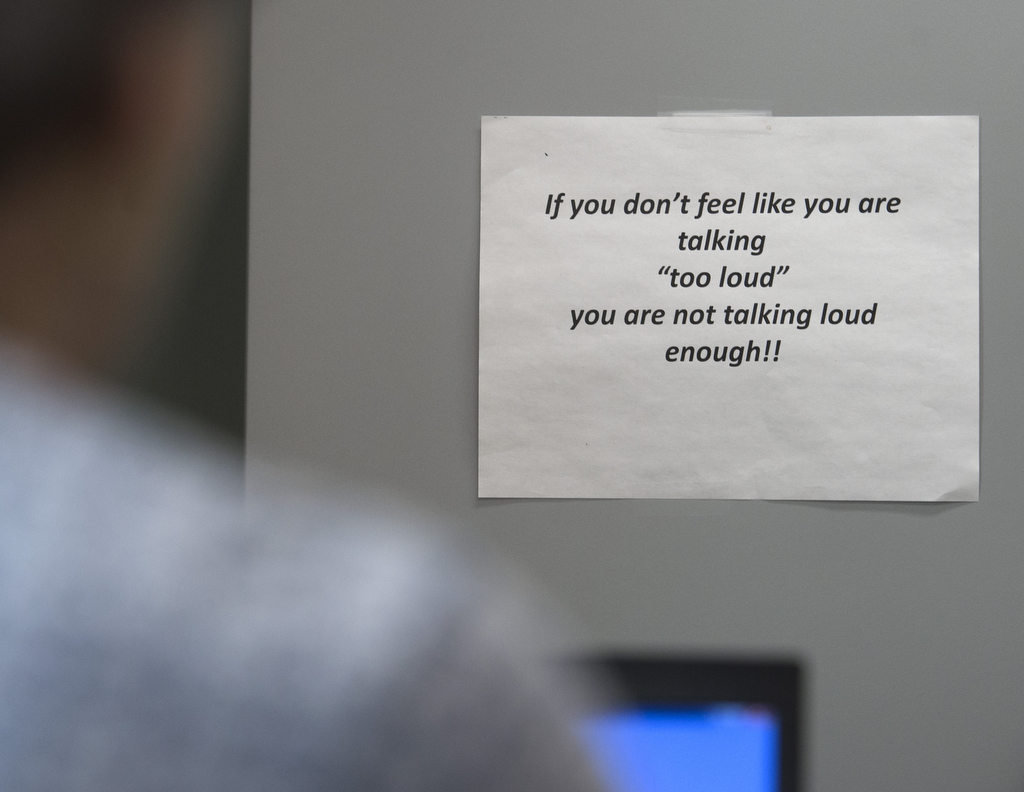

The changes occur so gradually they often go unnoticed by a person with Parkinson’s. The Big and Loud program helps patients become aware of their movements and speech―and the amount of effort required to make them “big and loud.”

“We are recalibrating their sense of normal movement,” Vryhof said.

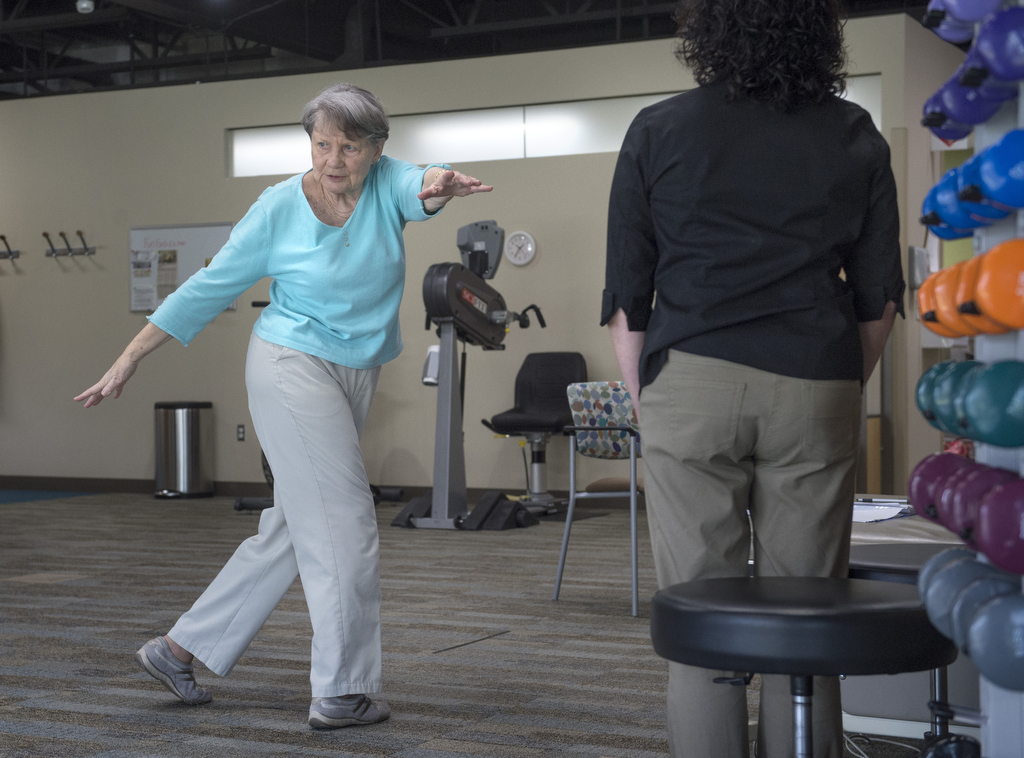

In one-on-one sessions, therapists tailor goals for patients, based on their interests, lifestyle and how far their Parkinson’s has progressed. Some struggle to get into bed on their own or to zip up a jacket. Others need to type quickly or give a presentation at work. Some want to swing a golf club.

The program builds on research that shows the benefits of exercise for Parkinson’s patients, said Ashok Sriram, MD, a Spectrum Health neurologist and movement disorders specialist. It improves mobility and voice as well as quality of life.

“The evidence of exercise in Parkinson’s is undebatable,” he said. “Exercise is medicine.”

Patients with Parkinson’s go through periodic assessments. Those who complete the Big and Loud program typically show clear gains in mobility, balance and speed of movement as well as the volume of their voice, Dr. Sriram said.

Eager to stay active

Ossewaarde, just diagnosed in January, said she has not lost a lot of ground to Parkinson’s. But she wants to maintain the balance, coordination and strength needed to stay active. She likes to garden, and she loves to babysit her great grandkids.

“I figure your muscles will atrophy if you don’t keep them stretched,” she said.

Parkinson’s has affected her voice the most. In recent months, when she said something to her husband, John, his response often was, “Huh?”

She didn’t realize how soft her voice had become until she began speech therapy.

In a recent speech therapy session, she ran through several vocal exercises. Then she took a deep breath and read through a list of everyday phrases she created.

“Where did you put my glasses?” she said. “It’s time to take my pills. Who is on the phone?”

A computer screen showed when she hit the right volume and when her voice dipped.

A strong voice and straight posture can make a big difference in a person’s ability to connect with others, the therapists said. Patients tell them the therapy helps regain the ability to join a conversation or take part in activities.

In a physical therapy, Ossewaarde went through a series of exercises that involved large movements. She swung her arms, stepped tall and moved side to side.

“All the exercises teach them to move with larger amplitude,” said physical therapist Yolanda Shafer, PT.

They help with balance, speed and strength―all factors that can reduce risk of falls.

Bowling better

Patients return for a follow-up evaluation six weeks after completing the program.

“Ninety percent or more of people in the program demonstrate some meaningful improvement,” Norbotten said.

The Big and Loud program generates excitement among therapists because past efforts to help Parkinson’s patients with therapy often did not create meaningful improvements. She believes Big and Loud leads to results because of the frequency of sessions and repetition of exercises.

Before starting the program, patients undergo an evaluation to identify their abilities and needs. If chosen for the “Loud” program, they receive speech therapy an hour a day. Those in the “Big” program receive an hour of physical or occupational therapy each day.

Ossewaarde, who took part in both programs, received 32 hours of therapy.

The change she noticed most as she progressed through the program was the improvement in her voice. Now, she knows how to make herself heard.

Another big improvement occurred at the bowling alley.

A bowler for 50 years, Ossewaarde gets together once a week with several friends to bowl.

“The first week (of Big and Loud), her average went up about 20 pins,” said her husband, John. Her three-game average rose from about 350 to more than 400.

At Lincoln Lanes recently, she sent the ball rolling down the alley and heard the heard satisfying crash as all 10 pins fell.

“I’m happy,” she said with a smile. Her tally for the game: 143.

The exercises she learned for her hands and fingers also have paid off. After she stretches and flicks her fingers, her handwriting improves and it’s easier to get a button through a buttonhole.

Before the program, Ossewaarde said she felt her fingers didn’t work well.

“I felt like there was sand and water between my skin and fingers,” she said. “And I don’t have that anymore.”

Dr. Sriram noted that medication also plays a role in the benefits seen by Ossewaarde. Exercise and medication complement each other.

Exercise as medicine

Ossewaarde plans to continue the exercises at home, as recommended by the therapists. The home exercises, which take 50 to 60 minutes a day, are crucial for continued success.

Patients return for follow-up assessments. If the progression of the disease or an injury creates new challenges, they may receive a tune-up―a short-term session of therapy―aimed at their current level of function.

The Big and Loud program does not take away Parkinson’s. Patients still live with a chronic, progressive neurological disorder.

“There is a general belief that it may slow down the progression of the disease, but the evidence is not conclusive,” Sriram said.

However, he sees quality of life benefits in patient after patient. If they continue with the exercises, they can push back against some of the debilitating symptoms.

“The capacity is there,” Vryhof said. “That’s one of the most exciting things that I’ve seen. They realize they can move better than they thought they could.”

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

/a>

Sharing…

Sharing…

Thank you, Lisa and Paula, for sharing this story! We hope it helps a lot of people. 🙂